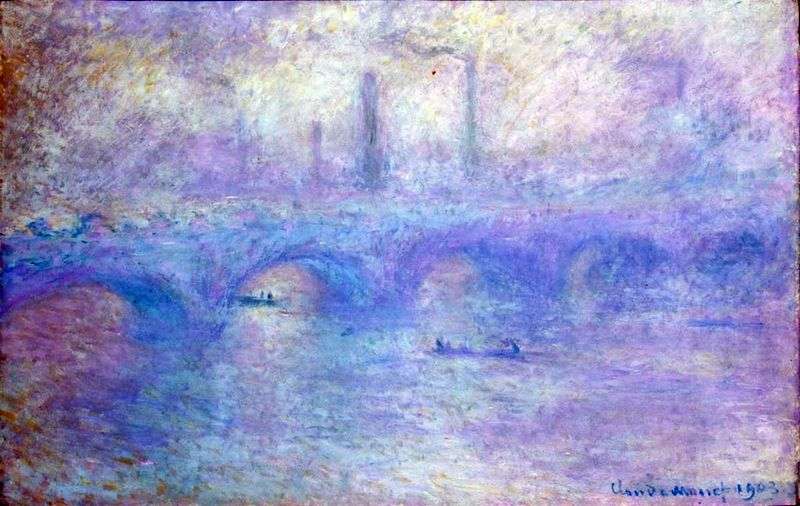

Monet’s picture is best viewed at some distance. The lilac color fills all its space, but the canvas cannot be called monotonous – the river and the sky are lighter than the bridge. On the canvas, a charming, soft, airy-light and pacifying view of the Thames opens up to the viewer’s eyes. The dense and at the same time difficult tangible volume of the work was achieved by the artist through the use of a huge number of tonal transitions, the shades of which are sometimes barely distinguishable. The whole range of tonality is quite wide and includes colors from dark blue to bright magenta. But these color transitions are made so skillfully that when looking at a picture at close range, the viewer does not see anything in front of him, except the canvas, on which frequent thick strokes of paint are applied.

All the magic of this work is revealed when the viewer moves away from the picture for some distance. At first, incomprehensible outlines of the semicircle, passing through the center of the picture, begin to appear before the apparent silhouettes of the boats appear, and already from a distance of about two meters from the picture all the pieces of the work are dramatically drawn and lined up into a single composition.

Now a view of the viewer is presented with a smoky air landscape depicting the archway of Waterloo connecting the districts of Westminster and South Bank, barges sailing under it and the smoking pipes in the industrial area of London shown in the background.

Despite the overall fluidity of the image and the smoothness of the tonal transitions, each specific element of the picture, when viewed in detail, stands out very clearly against the general background. Monet was able to achieve such a striking effect by using a sharper tonal gradation when moving from the imaged object to the background. The reflections on the water, depicted by the artist, cast by the arches of the bridge, look especially charming. Making an impression of absolutely unearthly and as if covered with some kind of sleepy veil, at the same time they convey quite realistic images. This perception of the image contributes to the realistic transfer of motion in the picture.

The foreground of the picture with the river Thames depicted on it and the floating barges is made by the artist in slightly brighter colors in comparison with the background. In this case, Monet used a frequent smear of medium size, moving diagonally from the middle of the canvas from left to right. With the same oblong strokes, the author slightly blurs the contour of the barge, creating in this way not only the fog effect, but also the sensation of the flow of the river. By contrasting it with the sky, depicted in the background in darker colors with brush strokes that do not have a common direction, Monet further enhances the dynamism of water.

It is also interesting that the artist used a special technique that draws purely on the psychological perception of the surrounding reality to attract the viewer’s attention to the picture. In a person’s life in a fog, in order to look at an object, it is necessary to come close to him. In the picture, the author went from the opposite, familiar to the human understanding of the phenomenon. And this successful trick worked. According to this scheme, for example, the inverted names “AMBULANCE” work on ambulances. Reflected in the rearview mirrors, they fall into the driver’s field of vision in a non-mirrored view. Thus, the artist was able to masterfully use not only his outstanding artistic talent, but also draw attention to the rich palette of colors created by him, affecting not only visual perception, but also psychological reflex.

Monet gained fame for his unique ability to convey on canvas the elusive moments of the surrounding reality. After all, neither sunset, nor dawn, nor fog can continue indefinitely. And the artist, who took up the brush, must have time to capture these magical moments on the canvas! Claude Monet coped brilliantly with this most difficult creative task. The extraordinary talent of the artist was explained by his contemporaries by the presence of his hypersensitive vision, thanks to which he was able to notice the smallest play of light and create the finest color gradations, giving the artistic images harmony and realism.

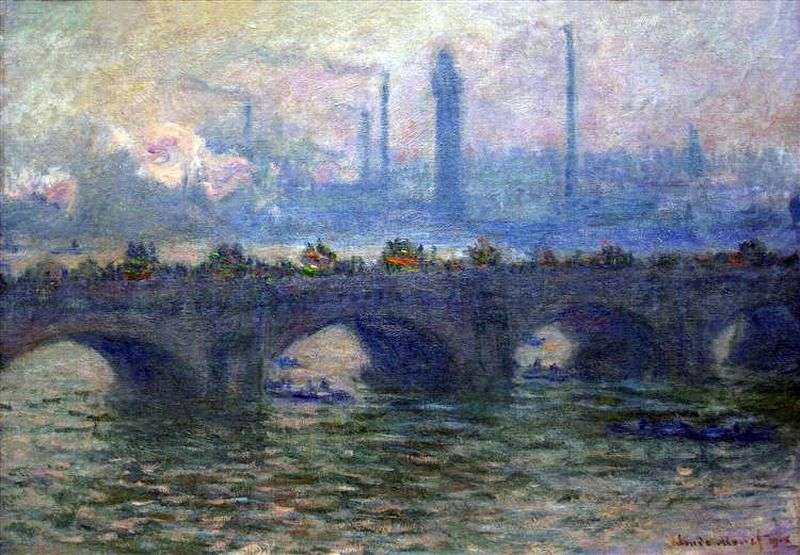

Waterloo Bridge by Claude Monet

Waterloo Bridge by Claude Monet Waterloo Bridge. Fog Effect by Claude Monet

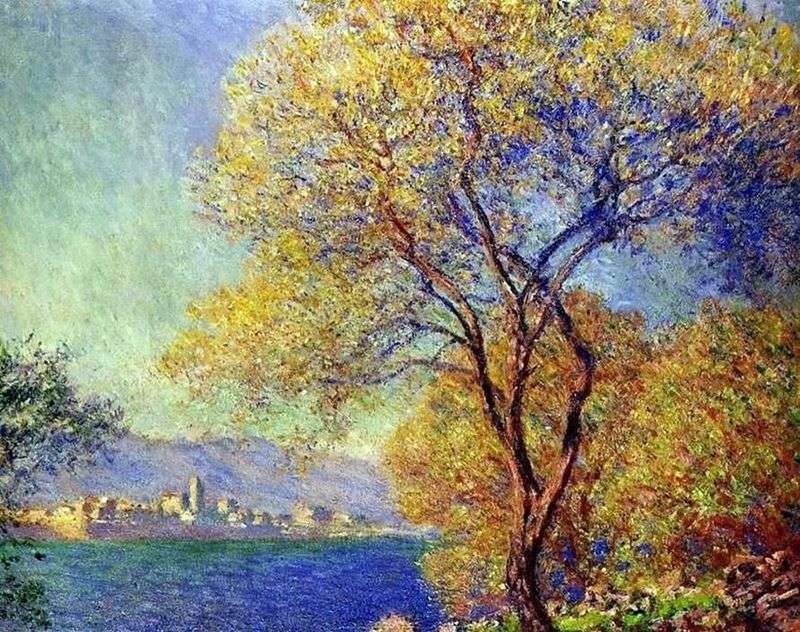

Waterloo Bridge. Fog Effect by Claude Monet Antibes in the morning by Claude Monet

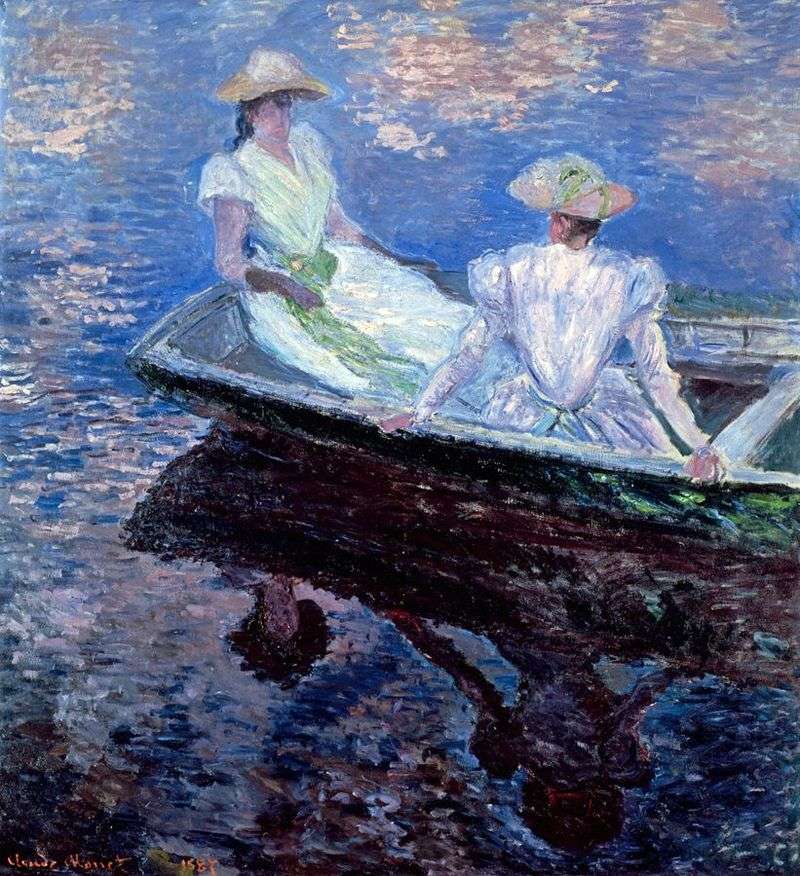

Antibes in the morning by Claude Monet Girls in a Blue Boat by Claude Monet

Girls in a Blue Boat by Claude Monet The banks of the Seine, Port Ville by Claude Monet

The banks of the Seine, Port Ville by Claude Monet Girls sailing in a boat on the river Ept by Claude Monet

Girls sailing in a boat on the river Ept by Claude Monet Irises by Claude Monet

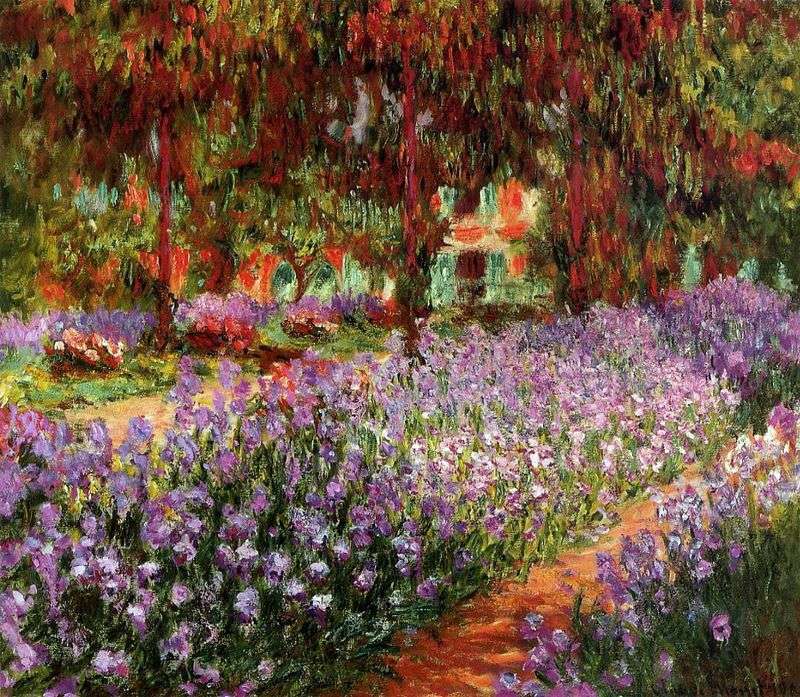

Irises by Claude Monet The Garden (Irises) by Claude Monet

The Garden (Irises) by Claude Monet