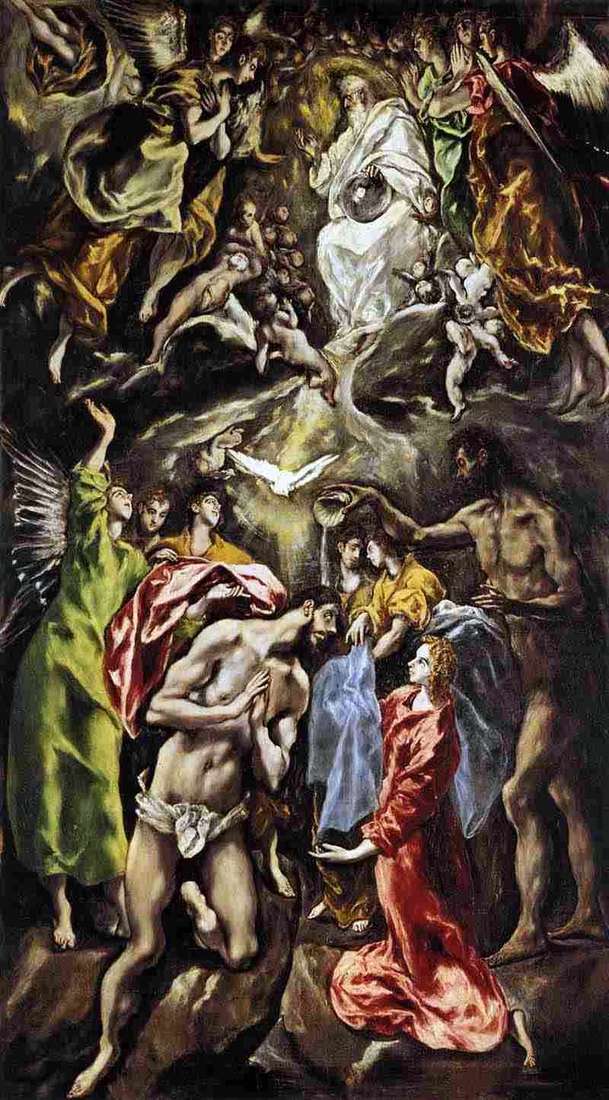

The huge, elongated canvas “Christening of Christ” is the only picture that is reliably known that it belonged to the altar cycle written by El Greco for the school of shod Augustines in Madrid, founded by the noble court lady Maria d’Aragon. This picture encompasses many features of the artist’s creativity in the second half of the 1590s.

The painting “The Baptism of Christ”, like other works of this period, located outside of Spain, creates a dazzling impression of the enlightened joy of visions. The image unfolds upward, the proportions of the figures are elongated, everything is embraced by a strong movement, the event occurs in a fantastic other world, where the lines between the earthly and heavenly are blurred.

Perhaps, among other paintings of this time, the “Baptism of Christ” is most strongly marked by a mystical character. A gentle Christ and ascetic John the Baptist, whose muscular body is modeled with confident picturesque freedom, are the most calm, steady images of the picture.

The environment around them embodies the divine emanation spread here. The artist seeks to increase the strength of the overall impression of the color of the light, the overload of the figures and the picturesque tension, which, according to Khamon Aznar, does not leave “pauses for relaxation.” The colorful surface of the canvas, permeated with flashes of light and as if seized by inner trepidation, becomes a sort of self-inspired spiritual matter.

El Greco perceives the movement here not so much as the physical movement of bodies in space, but as the emergence, formation and disappearance. One goes into another, dissolves in the glow of colors, fades and flashes, the faces of the angels tilt, lose outlines, their curls turn into golden aureoles, clothes phosphoresce with a bluish and green flame, silvery transparent wings tremble like the wings of dragonflies. A wavy contour line plays a huge role in the transmission of such motion.

The expressiveness of the line, the special significance of the outline, is the Eastern, Byzantine tradition in the work of the master. However, she rethought them in her own way. El Greco applies a system of linear rhythm that, even when it creates images close to reality, does not coincide with the organic form. It is like a linear pattern, superimposed on the image and subordinating it to himself. There is a discrepancy, distortion, the figures of El Greco give the impression of deformed, often awkward, especially in the outlines of legs and hands. But the ideal beauty did not bother the painter, and in a similar displacement, as well as in violation of proportions, he saw one of the expressions of the spiritual.

The continuous line that delineates the outline of figures, for example, in the depiction of Christ and John the Baptist in the mentioned Madrid painting, becomes, in the words of M. V. Alpatov, in the works of El Greco “The compressed rhythm formula that permeates all living things, all organic matter.”

The Baptism of Christ by Piero della Francesca

The Baptism of Christ by Piero della Francesca Christ carrying the cross by El Greco

Christ carrying the cross by El Greco Holy Trinity by El Greco

Holy Trinity by El Greco Fresco Baptism of Christ by Pietro Perugino

Fresco Baptism of Christ by Pietro Perugino The Baptism of Christ by Leonardo da Vinci

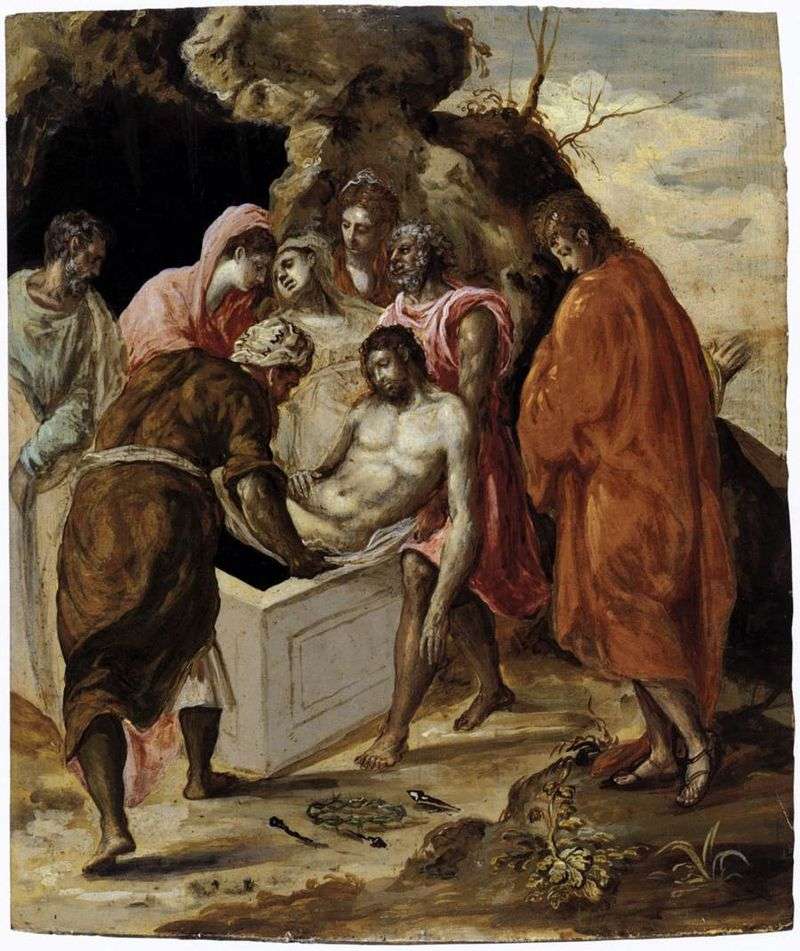

The Baptism of Christ by Leonardo da Vinci The Position of Christ in the Coffin by El Greco

The Position of Christ in the Coffin by El Greco Worship of the Name of Christ by El Greco

Worship of the Name of Christ by El Greco Christ heals the blind by El Greco

Christ heals the blind by El Greco