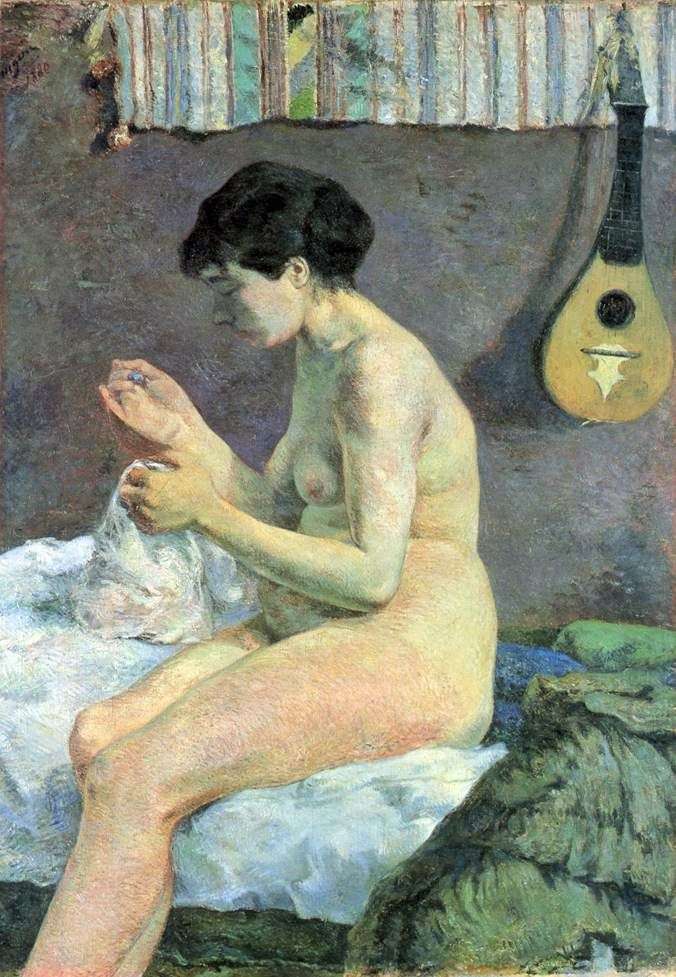

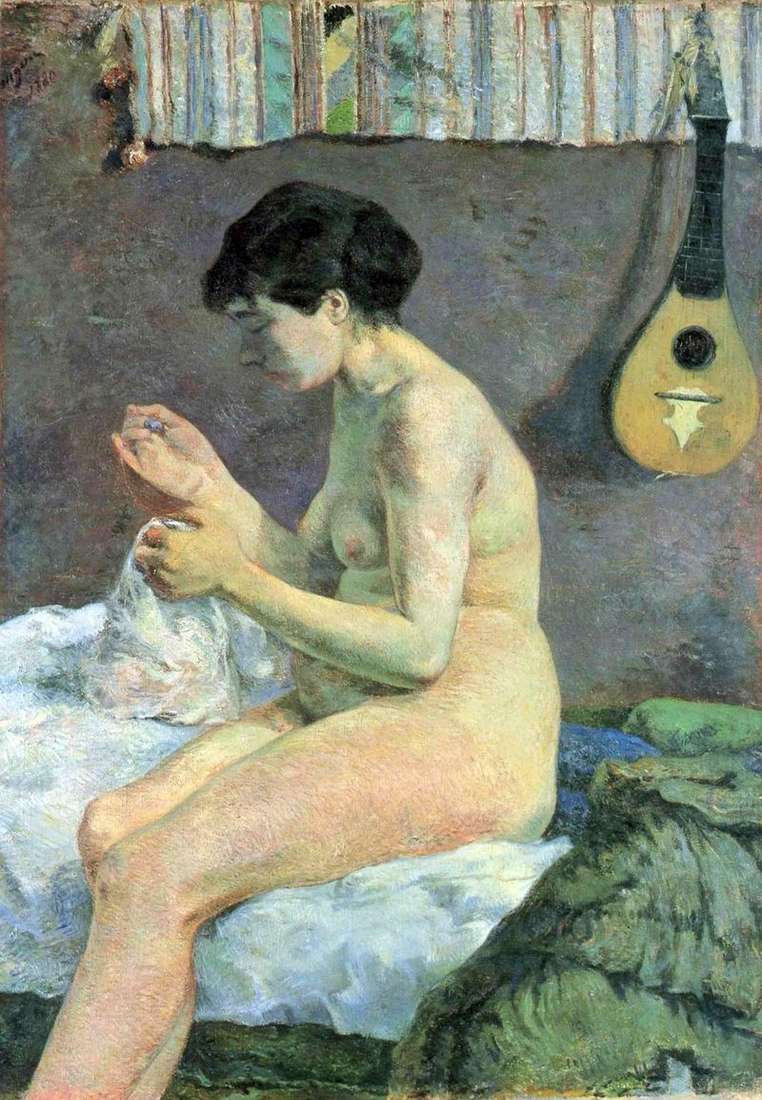

In 1880, Gauguin wrote a nude woman – Justine’s maid posed for him. In this nude Gauguin, as fully as possible, expressed what distinguished him from the Impressionists. In fact, it is difficult to find anything in common between a woman sitting on the edge of the sofa and bending her cheerless face over the cloth she is mending, and the naked women of Renoir, with their blooming and sparkling flesh! Brush Renoir caresses the surface of the skin. Under the brush of Gauguin, through the form of the body, the soul emerges.

Renoir and other Impressionists write the visible, Gauguin, consciously or not, tries to write what is outside the visible, what the visible to some extent reflects. This nude stood out against the backdrop of other works by Gauguin himself and his comrades that at the sixth exhibition of the Impressionists in April 1881 in the house number 35 on the Boulevard de Capuchin where this picture hung, she for a long time riveted the attention of the writer-naturalist Huysmans. “Last year,” wrote Huysmans, “Mr. Gauguin exhibited… a series of landscapes – a sort of liquefied, fragile Pissarro.” This year, Mr. Gauguin presented the product truly independent, a painting that shows the incontrovertible temperament of a contemporary artist.

The painting is called “Etude of Nudity.” I dare say that none of the modern artists who worked on nudity, with such force did not sound the truth of life… This flesh cries. No, it’s not that even, smooth skin, without pimples, specks and pores, the skin that all artists are dipping into a vat with pink water and then ironing with a hot iron. It is red from the blood of the epidermis, under which nervous fibers tremble. And in general, how much truth in every particle of this body – in a fat belly, hanging down thighs, wrinkles under the bent breast, surrounded by a bistre, in knobby joint knuckles, in bony wrists! .. Over the years, Mr. Gauguin first tried to portray the modern a woman… He completely succeeded, and he created a fearless, truthful picture. “

After that, Huysmans briefly mentioned the seven other paintings, a wooden “gothic modern” statuette and a medallion of painted gypsum, with which Gauguin was represented at the exhibition. “But in the landscapes, Mr. Gauguin’s individuality is still struggling to get out of the embrace of his mentor, Mr. Pissarro,” Huysmans wrote with mild disdain. Praises of Huysmans saved Gauguin from doubts: he is an artist, a true artist, and not an amateur. But these praises should have embarrassed him. Huysmans generally praised him for realism, and Gauguin, of course, felt the same instinctive doubt with respect to realism as with respect to impressionism. In fact, impressionism was the heir of realism. In both cases it was a question of depicting “visible objects”, however, by various means.

Much later, when Gauguin becomes clear about the meaning of his own searches and he understands what they are leading to, he will not accidentally tell about impressionists that they conducted their searches “around the visible to the eye, and not in the mysterious center of thought.” The naked, admiring Huysmans, with her heavy, unattractive body, with her expression of sadness, was not at all the heroine of the naturalistic “slice of life.” She was the messenger of Gauguin’s inner world, that unknown world, the first unexpected manifestation of which was this canvas… “

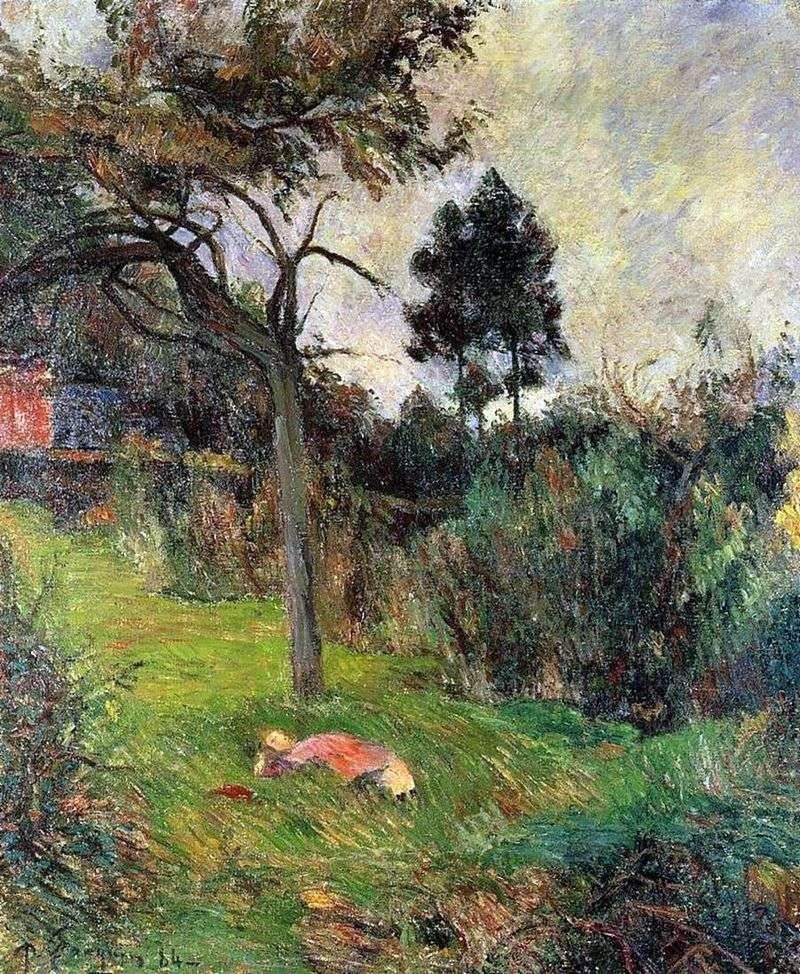

Young woman lying on the grass by Paul Gauguin

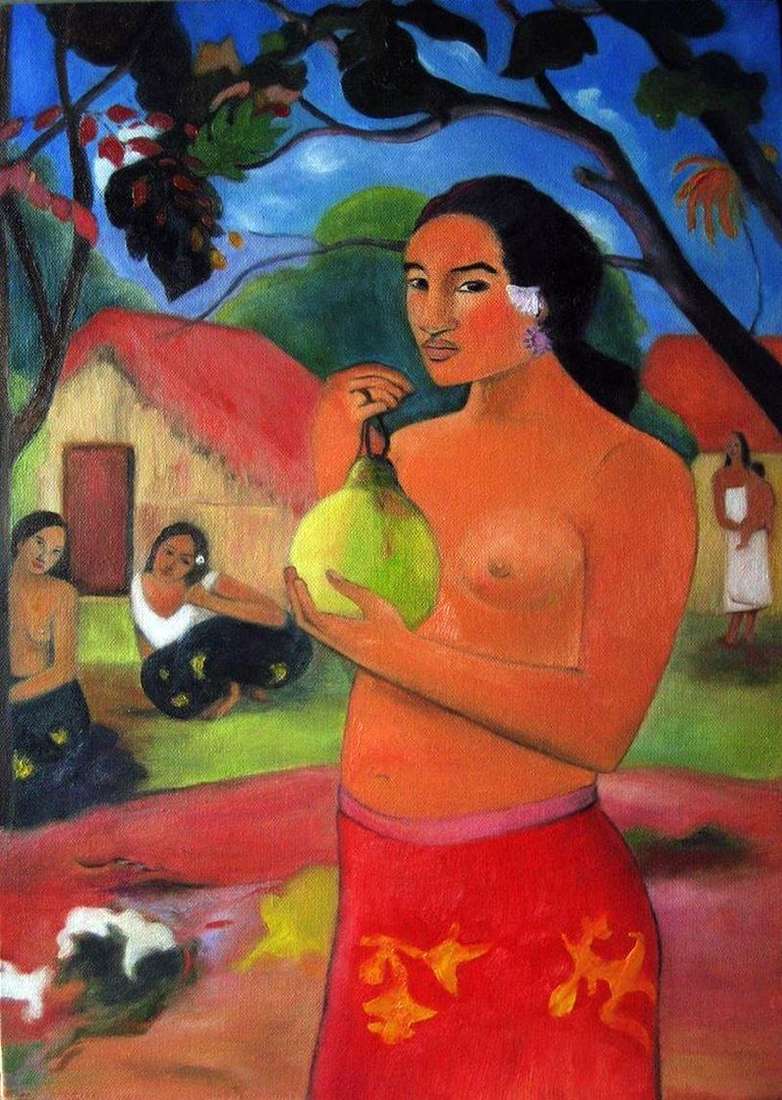

Young woman lying on the grass by Paul Gauguin Woman holding the fruit by Paul Gauguin

Woman holding the fruit by Paul Gauguin Tahitian woman with a flower by Paul Gauguin

Tahitian woman with a flower by Paul Gauguin Woman with flower by Paul Gauguin

Woman with flower by Paul Gauguin Nude by Paul Gauguin

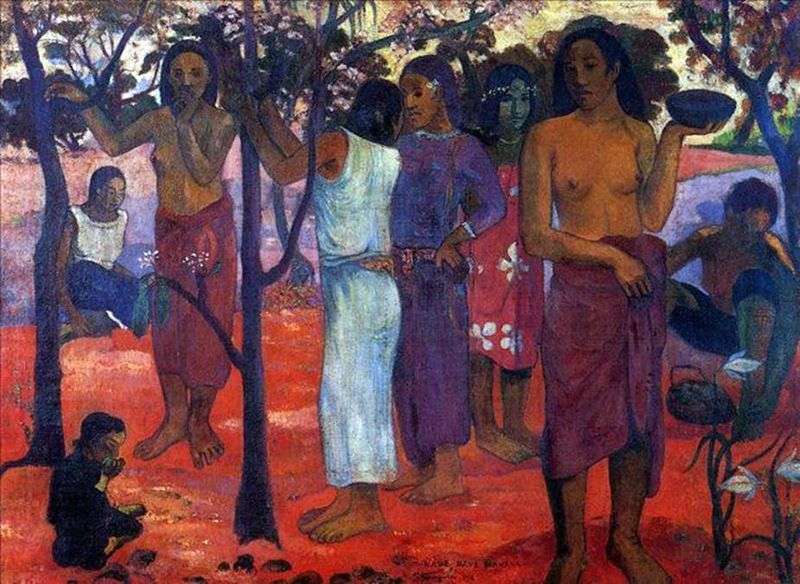

Nude by Paul Gauguin Beautiful days by Paul Gauguin

Beautiful days by Paul Gauguin Woman with a mango (Girl with a mango fruit) by Paul Gauguin

Woman with a mango (Girl with a mango fruit) by Paul Gauguin Mette Gauguin in an evening gown by Paul Gauguin

Mette Gauguin in an evening gown by Paul Gauguin