The common theme of all portraits is the tragic conflict between art and everyday reality, between the artist and the surrounding society, that “secular rabble”, about whom in the same thirties and forties of the last century, with great contempt and anger, the great Russian poets spoke.

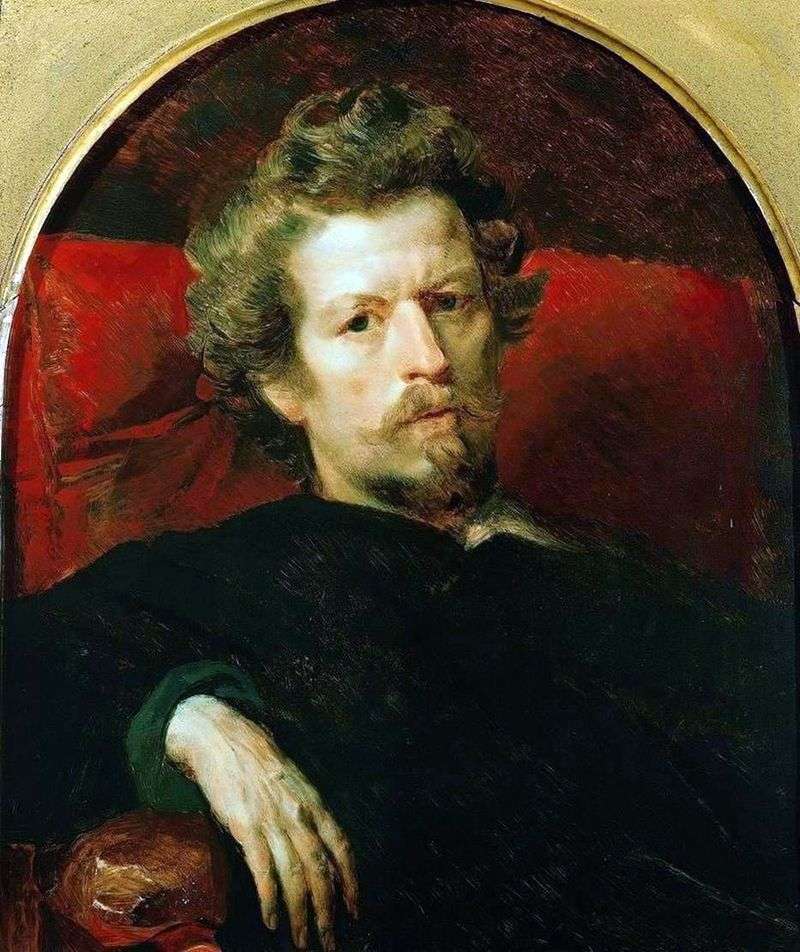

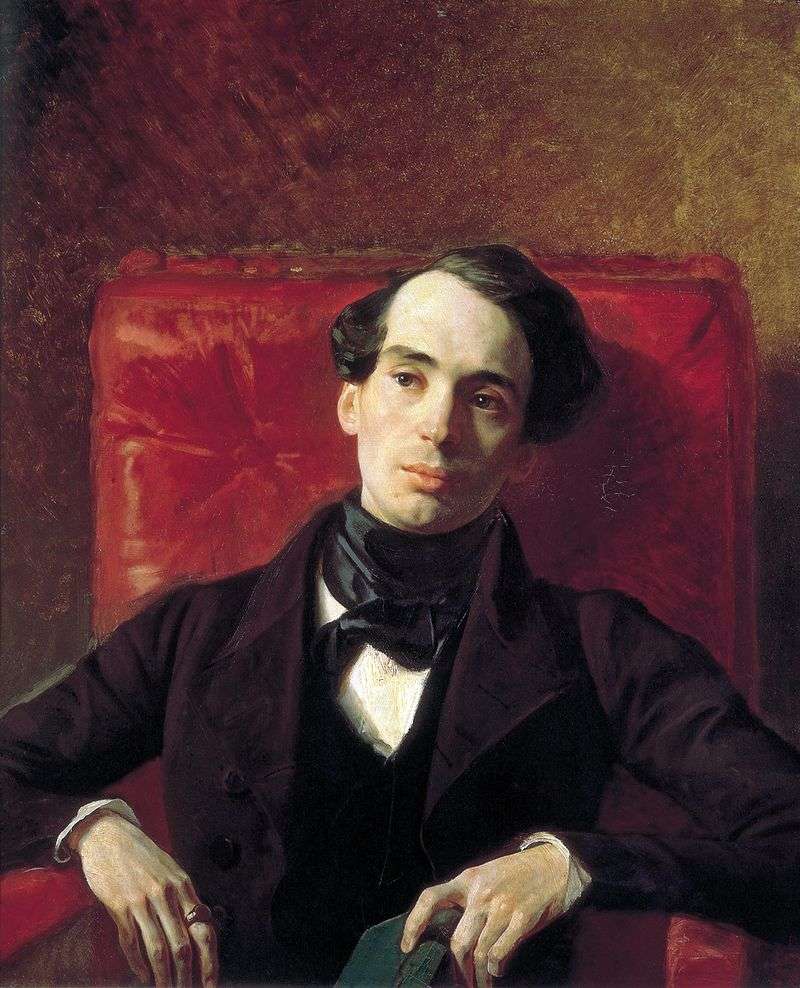

Romantically understood tragedy of creativity becomes the central problem of the whole cycle of portrait works of Bryullov. With an extraordinary force of artistic generalization, Bryullov created in the portrait of N. Kukolnik an image of a romantic poet, in the portrait of A. Strugovshchikov gave the collective type of an intellectual of the thirties, the direct predecessor of “superfluous people,” later depicted by Russian literature. But with the greatest clarity, all these problems are in the famous “Self-portrait.” According to a just comment of one of the Soviet researchers, “this portrait reveals better than any words to us the spiritual drama of the artist, hidden under the external glint of glory.” Bryullov pretended to be half-lying; his head is thrown back, and a thin, carefully written hand rests on the velvet arm of the chair.

The artist’s face, emaciated and pale, is marked with a seal of a deadly ailment, but the intense look of deep-seated blue eyes speaks of unshaken internal strength. The artist, apparently, wanted to emphasize here the struggle of the unquenchable creative spirit with impotent flesh, hence the expression of his face is characterized by such soulful spirituality.

Bryullov painted his portrait during a serious illness, which later proved to be fatal. But it would be erroneous to explain the tragic expression of “Self-portrait” only by the premonition of a near death. The content of the “Self-portrait” is much more significant and deeper. Without fearing exaggeration, it can be argued that Bryullov as if sums up the result of all lived life and that the image of the romantic artist created by him is deliberately opposed to the modern bureaucratic serf society. The portrait was written in 1848, at the time of the worst Nicholas reaction. Bryullov was right to consider himself one of her victims.

The entire St. Petersburg period of his life externally, seemingly full of success and marked by a noisy glory, was in fact deeply tragic. Bryullov was suffocating in the deadening, official atmosphere of Nikolayev’s Petersburg. The talent of the remarkable artist did not find a worthy use. Instead of free creativity, Bryullov was invited to paint the St. Isaac’s Cathedral, although religious painting was completely alien to the nature of his talent.

The historical picture of the “Siege of Pskov”, in which Bryullov saw the main cause of his life, was placed under official supervision and, under the pressure of the tsar and his entourage, was repeatedly subjected to radical processing. It was never finished until the end. Bryullov’s dream did not come true, to create a work more significant than “The Last Day of Pompeii,” and to lead the new national trend in Russian art. The feeling of bitter dissatisfaction did not leave the artist, a painful sense of dependence constrained his strength.

The collapse of his best intentions and explains that harsh hopelessness, that tragic pathetic, which will penetrate the “Self-portrait.” Curious information about this work is reported by MI Zheleznoy, the student and biographer of Bryullov: “On that day, as the doctors allowed Bryullov to get out of bed, he sat down in a Voltaire chair, standing in his bedroom opposite the dressing-table, demanded an easel, cardboard, palette; he charted his head on the cardboard and asked Koritsky to prepare for the next morning a paler fattier. It was not sure that he would do anything decent, and so in the evening he gave the order not to let anyone else for him until the next day until he finishes work.

Later I learned from Bryullov himself that he had used two hours to perform his portrait. Bryullov was very short-lived for this portrait… I found in him a great resemblance to the original in minutes, but this resemblance was constantly eluding me and being replaced by something else. “The mention of this elusive and fleeting similarity is extremely characteristic: Bryullov portrayed himself in a minute of high creative inspiration, transforming his habitual, well-known to the disciples look.

In “Self-portrait” is captured the image of a creative artist. Even more interesting is the indication that the portrait was written in one session, without a preliminary sketch and preliminary sketches. The same technique of the “Self-portrait” testifies to the same thing, it was not smoothed out, as in other works, but, on the contrary, it was underlined free, with wide and daring strokes applied in a thin layer. In this inspired improvisation with special brilliance is the virtuoso skill of Bryullov. Each smear is laid with infallible accuracy, sharply noticed contrasts of light and shade perfectly mold the shape, in the reddish-brown range that unites the portrait, various and subtle shades of color are carefully traced.

The historical and artistic significance of the “Self-portrait” is, however, conditioned not by the formal perfection of its solution, but by the profound meaningfulness, vitality and psychological truthfulness of the image. “Self-portrait” Bryullov stands among the best realistic achievements of Russian painting in the first half of the XIX century.

Portrait of Vel. Book. Yelena Pavlovna by Karl Bryullov

Portrait of Vel. Book. Yelena Pavlovna by Karl Bryullov Portrait of Yu. P. Samoylova with Giovannina Pacini and Arapchonka by Karl Bryullov

Portrait of Yu. P. Samoylova with Giovannina Pacini and Arapchonka by Karl Bryullov Portrait of AN Strugovshchikov by Karl Bryullov

Portrait of AN Strugovshchikov by Karl Bryullov Portrait of VA Zhukovsky by Karl Bryullov

Portrait of VA Zhukovsky by Karl Bryullov Portrait of Countess Samoilova by Karl Bryullov

Portrait of Countess Samoilova by Karl Bryullov Portrait of MA Kikina by Karl Bryullov

Portrait of MA Kikina by Karl Bryullov Portrait of Archaeologist Michelangelo Lanci by Karl Bryullov

Portrait of Archaeologist Michelangelo Lanci by Karl Bryullov Portrait of musician M. Yu. Vielgorsky by Karl Bryullov

Portrait of musician M. Yu. Vielgorsky by Karl Bryullov