In the motley picture of numerous sculpture schools, which worked mostly isolated from each other, one can nevertheless note the general tendency to develop new, Renaissance artistic elements, expressed in various, albeit unsystematic, searches for realistic truthfulness. These traits are affected, for example, in unexpectedly correct proportions and the calm rigor of the simple and purely human appearance of the crucified Christ, performed for the altar of St. George in Niederlingen by Simon Leinberger in 1478-1480. They are also manifested in the cozy hospitality and simplicity of the “Dangelsheim Madonna”, created by the same master. This general attraction to secular interpretation of human images takes on an exaggerated grotesque shape in the curious wooden painted figures of dancing jesters, performed in 1480.

Although the noted secular, realistically truthful elements act in isolation and can not yet overcome in the sculptural monuments the Gothic pattern of silhouettes, the whimsicality of sharp, sharply collapsing folds, yet some of the works of German sculpture of the late 15th century. They bear in themselves the clear features of the foreknowledge of liberation from medieval stiffness and abstraction. Speaking in these works, interest in the transfer of the structure of the human body, in establishing correct proportions and in the embodiment of living feelings, prepares the ground for the destruction of old medieval art from within, replaced by an artistic style engendered by other aesthetic demands.

Muzio Scaevola ante el rey Porsen – Hans Baldung

Muzio Scaevola ante el rey Porsen – Hans Baldung Mutsius Stcevola devant le roi Porsen – Hans Baldung

Mutsius Stcevola devant le roi Porsen – Hans Baldung Allegory of Music by Hans Baldung

Allegory of Music by Hans Baldung Madonna and Parrot by Hans Baldung

Madonna and Parrot by Hans Baldung Eva, the snake and death by Hans Baldung

Eva, the snake and death by Hans Baldung Prudence by Hans Baldung

Prudence by Hans Baldung Knight, young girl and death by Hans Baldung

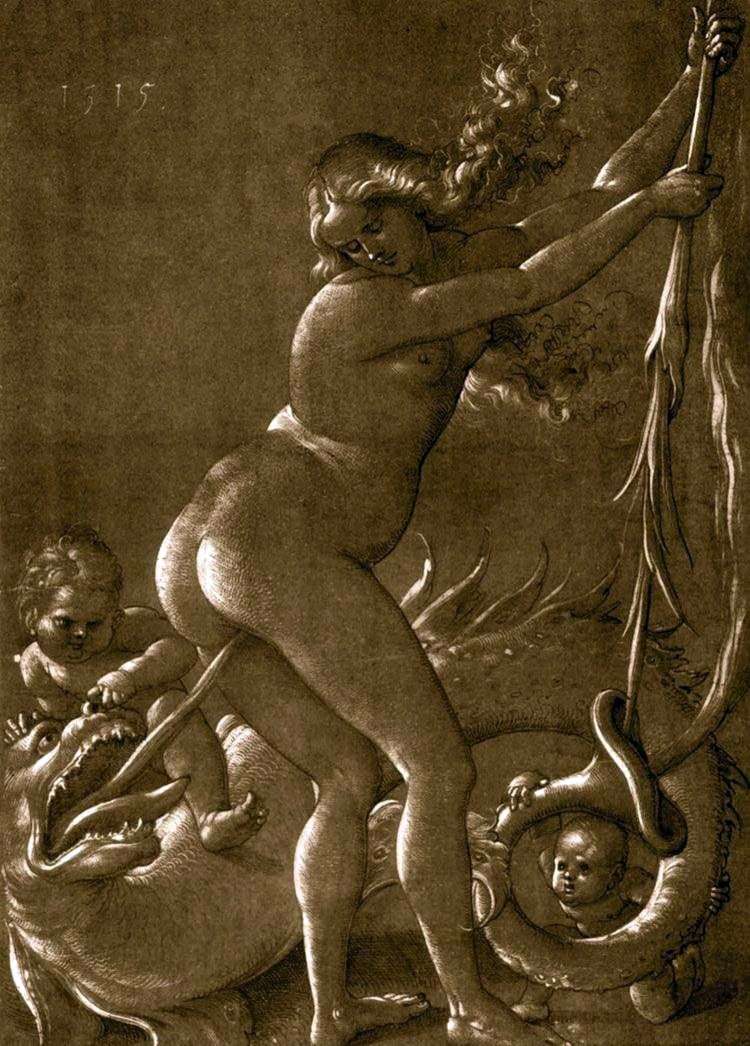

Knight, young girl and death by Hans Baldung Witch and Serpent (engraving) by Hans Baldung

Witch and Serpent (engraving) by Hans Baldung