Since 1883, Claude Monet’s reputation as a talented painter was entrenched, and his financial situation improved, and he, like other Impressionists, began to seek solitude. In fact, for many years Monet lived far from Paris, after Arzhanteyya was stuck in Veteil for seven years. Now, together with Alice Goshede, who became his second wife, her six children and her two sons after the death of her husband in 1892, he settled in Giverny, a tiny village located not far from the confluence of Epta and the Seine. Thus, Monet lived in places that he had fallen in love with since the time of Bennecur, finding picturesque corners resembling Vetey.

The success of his canvases by that time became obvious, and Octave Mirbeau prepared an article for Figaro for printing, where he wrote: “Claude Monet won a victory over the enemies today, he silenced everyone around. He, as they say,” succeeded. ” stubborn people still consider art to be a frozen, dead formula and argue about the peculiarities of his talent, they no longer dispute the fact that this talent really exists and is able to force itself to admit it, because it has the power and charm that penetrates to the very bottom souls. Lovers, earlier the ones who mocked him are now honored to have his canvases in their collections; the artists, who most often mocked him, now zealously imitate him. ” Similar lines from the newspaper, where the terrible Albert Wolf still printed his prose writings, are a sure testimony to the success of Monet and his friends a decade after the first exhibition at Nadar. As more money grew, Monet landscaped and expanded the house, first renting it, and then buying it in 1890.

Later, he built a workshop in the garden, in 1911, he worked here on the scenery for the Orangeries based on the etudes to White Lilies. The entire Giverni period, stretching almost half a century, passed under the sign of “Lily pads”. For twenty-five years, leaning over the surface of the reservoir, Monet endlessly wrote water lilies, aquatic plants, weeping willow. This series of sketches was preceded by another – “Rouen Cathedrals”, “Topol”, “Mills”, after which the artist started on the “Water Lilies”. The long period of creativity associated with Giverny, marked by another passion of the artist, captured him no less than the study of light glare. Monet got carried away gardening. It interested him earlier. And in Saint-Michel, and in Argenteuil, and in Veteil, despite scarce means, He managed to plant small gardens with overgrown flower beds. At Giverny, his passion has gone mad. The layout of the garden created by the artist, which varied depending on the season, was thought out to the smallest detail.

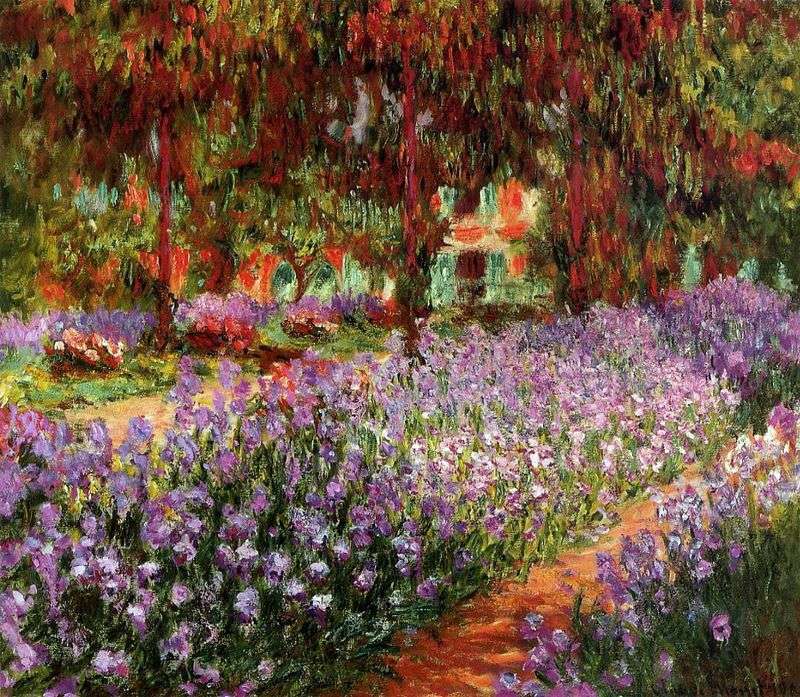

First of all, work was done on the approaches to the house: Monet cut down the alley of spruce and cypress trees, considering it too dull, retaining only high stumps for which the branches of the climbing rosehip were clinging, which soon closed and turned into a flower vaulted tunnel above the path that led to the house from the gate. Later, when the stumps collapsed, he replaced them with metal arms, gradually growing flowers. Feeling an aversion to large ornamental beds, which the bourgeois usually arrange on their lawns, he planted heaps or in the form of borders irises, phloxes, delphiniums, asters and gladioli, dahlias and chrysanthemums, as well as bulbous plants that looked on bright green background of English lawns like a luxurious mosaic carpet. There is no doubt that his experienced eye could skillfully mix colors of colors to achieve harmonious combinations, contrasts and transitions. Having finished the flower garden at the house, Monet bought a large swampy piece of land on the other side of the road, which bordered on his garden, and drained it on his spare cash. Having made a small ditch that connected his section with the river Epta, he was able to fill a small, irregularly shaped artificial reservoir with water, threw a Japanese bridge over it, from which fragrant purple and white wisteria lace hung. The pond was planted with water-lilies of all kinds, and a hedge of irises and arrowheads was arranged around the edges. In the book devoted to Monet, his stepson J. P. Goshede noted that the artist was most important of all not a curiosity, but the impression made by her. The impression of the details and of the whole. Monet bought a large marshland on the other side of the road, which bordered his garden, and drained it on his available funds. Having made a small ditch that connected his section with the river Epta, he was able to fill a small, irregularly shaped artificial reservoir with water, threw a Japanese bridge over it, from which fragrant purple and white wisteria lace hung. The pond was planted with water-lilies of all kinds, and a hedge of irises and arrowheads was arranged around the edges. In the book devoted to Monet, his stepson J. P. Goshede noted that the artist was most important of all not a curiosity, but the impression made by her. The impression of the details and of the whole. Monet bought a large marshland on the other side of the road, which bordered his garden, and drained it on his available funds. Having made a small ditch that connected his section with the river Epta, he was able to fill a small, irregularly shaped artificial reservoir with water, threw a Japanese bridge over it, from which fragrant purple and white wisteria lace hung. The pond was planted with water-lilies of all kinds, and a hedge of irises and arrowheads was arranged around the edges. In the book devoted to Monet, his stepson J. P. Goshede noted that the artist was most important of all not a curiosity, but the impression made by her. The impression of the details and of the whole. an irregularly shaped artificial reservoir, threw a Japanese bridge over it, from which fragrant lilac and white wisteria lace dangled. The pond was planted with water-lilies of all kinds, and a hedge of irises and arrowheads was arranged around the edges. In the book devoted to Monet, his stepson J. P. Goshede noted that the artist was most important of all not a curiosity, but the impression made by her. The impression of the details and of the whole. an irregularly shaped artificial reservoir, threw a Japanese bridge over it, from which fragrant lilac and white wisteria lace dangled. The pond was planted with water-lilies of all kinds, and a hedge of irises and arrowheads was arranged around the edges. In the book devoted to Monet, his stepson J. P. Goshede noted that the artist was most important of all not a curiosity, but the impression made by her. The impression of the details and of the whole.

The continued creation of the garden inspired Monet, and he conscientiously studied the trade catalogs, constantly ordering all the new seedlings. For receiving first-hand reliable information, he hosted the most important gardening specialists at dinner and became especially friendly with Georges Truffaut. Although such a passion cost a lot of money, for it required the constant presence of five gardeners, it turned out to be worthless as soon as the artist began to write water lilies. About a hundred etudes and finished canvases were created by him on this topic, and they are perhaps the most admired, especially since many works were performed during the exacerbation of glaucoma, which threatened Monet’s vision, and therefore are close to abstract painting.

It was these works written during the illness that led the American researcher Alfred Barr, Jr., who studied them thoroughly, to conclude that Monet was one of the founders of the informal abstract art. It is doubtful that it was precisely this goal that the creator of Lily Pads set for himself, especially since, having recovered after the operation, he regained the ability to see objects in a special way, that ability, which Odilon Redon critically and admiringly remarked: “Monet is always the eye, but what! ” Having fallen into the trap of abstractionism, connoisseurs of painting after the war literally pulled out the canvases from each other, which were no longer needed by anyone and left by Michel Monet to rot in Giverny, in the workshop where the glasses were broken by the American bombings during the battles for the liberation of France.

Renovated after a long period of desolation due to the generosity of American and French patrons, Claude Monet’s garden was widely known at the beginning of the century. Georges Clemenceau, who knew the artist from the time of Herbouat and owned one of the village houses near Giverny, was so amazed by this event that he even dedicated a small brochure to him in which he wrote: “The garden of Claude Monet can be considered one of his works, In it, the artist miraculously realized the idea of transforming nature according to the laws of light painting. His workshop was not limited to walls, it went out into the open air, where color palettes were scattered everywhere, training the eye and satisfying the insatiable appetite of the net. ki, ready to accept the slightest flutter of life. ” Monet and Clemenceau were close, this is a known fact. On November 18, 1918, Clemenceau arrived in Giverny to inform the artist about the acceptance of his “Lilies” by the state commission. This, no doubt, was also a victory, because the administration of the Fine Arts was still under pressure from the latest pomperists from the jury of the Salon and the heads of the Institute and put all sorts of obstacles to such a decision… “

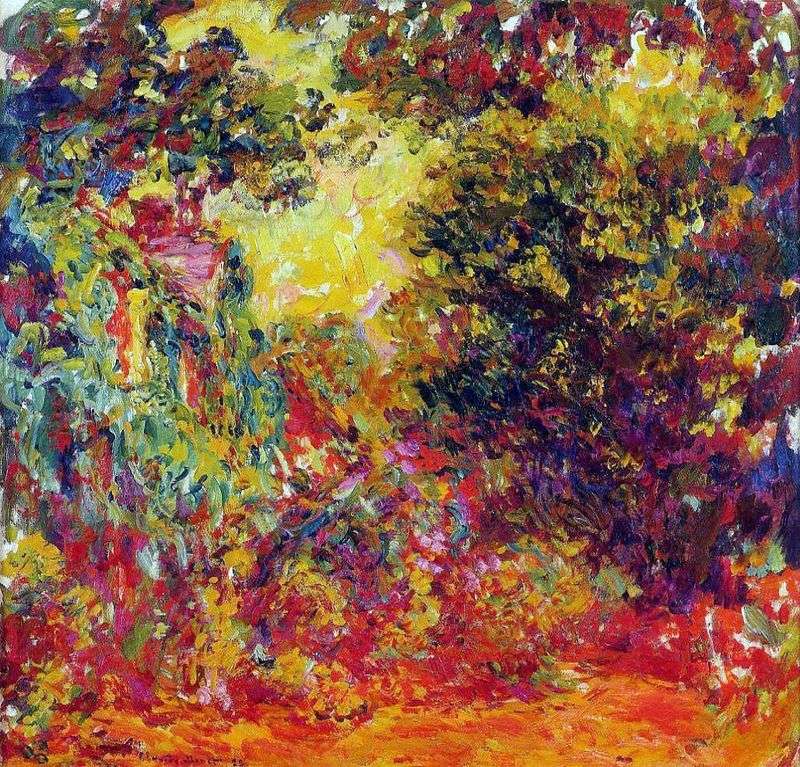

Main path through the garden in Giverny by Claude Monet

Main path through the garden in Giverny by Claude Monet Water Garden by Claude Monet

Water Garden by Claude Monet Girl in the Garden, Giverny by Claude Monet

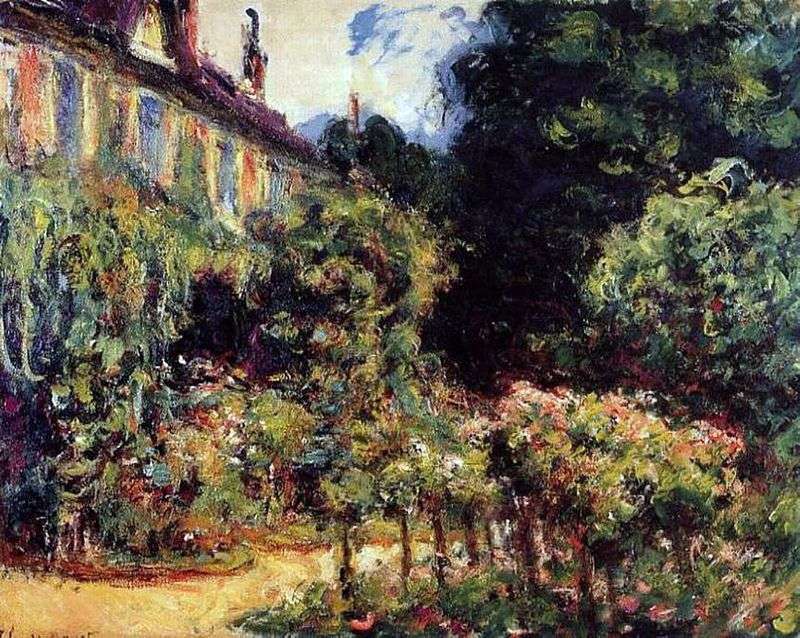

Girl in the Garden, Giverny by Claude Monet House of Artists, view from the rose garden by Claude Monet

House of Artists, view from the rose garden by Claude Monet Japanese Bridge by Claude Monet

Japanese Bridge by Claude Monet Artist’s House in Giverny by Claude Monet

Artist’s House in Giverny by Claude Monet The Garden (Irises) by Claude Monet

The Garden (Irises) by Claude Monet