One of the most significant events in the artistic life of Paris at the beginning of the 20th century was the Autumn Salon of 1905, the opening of which was accompanied by a scandal. Several young artists, grouped around Henri Matisse, exhibited there a number of works that caused an outburst of indignation from the public and French criticism accustomed to the sensations. Written in bright, glowing colors, with an emphasized disregard for the rules of drawing and perspective, without any seemingly concern for credibility, these works were perceived as a daring challenge to “common sense” and “good taste.”

The audience nicknamed the young painters Les fauves, from which the term Fauvism subsequently arose. By the time of the first Fauvist performances, the paintings of the recently deceased Gauguin did not cause indignation from the majority, although a number of features brought them closer to the works of young innovators. Gauguin was always present element of the exotic, which in the eyes of the public justified the convention of his artistic language. The Fauvists, on the other hand, reproduced the everyday, everyday, but transformed the one depicted with unprecedented boldness.

In a certain respect, they were closer to the real image of phenomena than Gauguin. The latter, as a rule, refused to transfer the lighting, while Matisse and his comrades re-created solar effects on their canvases. However, for their purpose, they used the new artistic language. Color in the works of the Fauvists most often does not convey the real coloring of objects; another function is assigned to it – it must cause certain, quite distinct associations in the viewer. The Fauvist group did not last long. After one or two years, the young artists went their separate ways – each went his own way. In 1908, in one of the articles, Matisse formulated his task in art as follows: “What I dream about is balanced art, pure, calm… that would be for every human being…

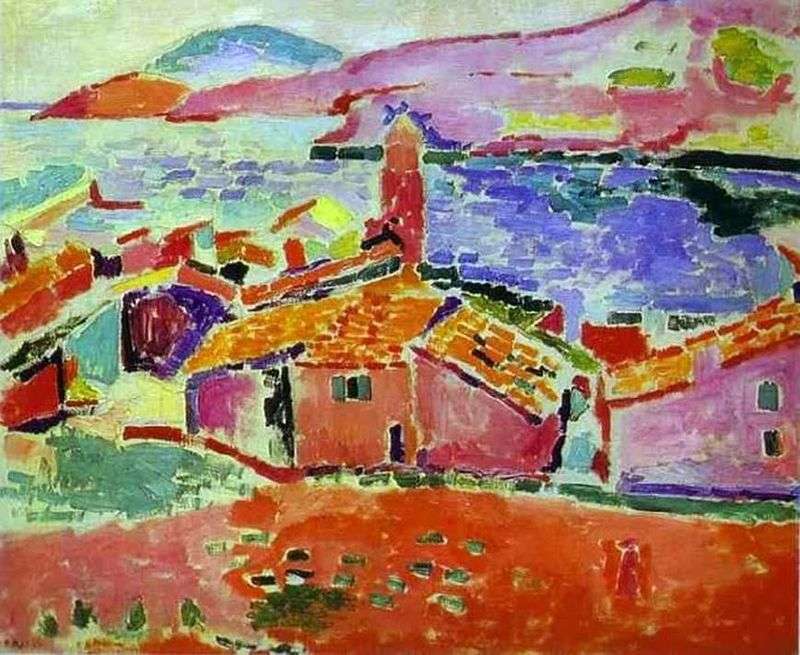

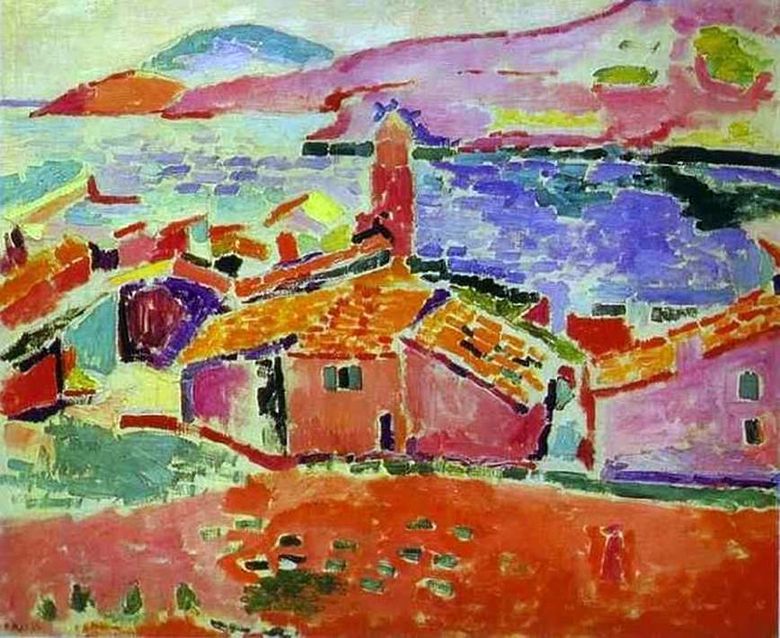

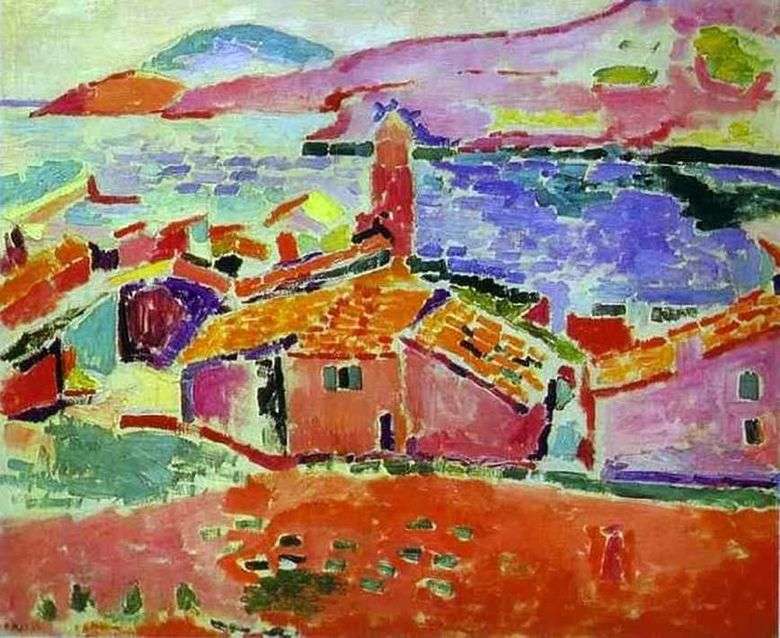

View of the small town of Collioure was written by Matisse in the sultry south afternoon. Objects are devoid of clear outlines. Initially, the viewer sees a solid color haze, in which bright, like pulsating, colorful spots float. Gradually, he begins to navigate in this chaos, as colorful as a patchwork quilt. The sky in the landscape is white from the heat. The outlines of purple mountains melt in the whitish haze, the blue color of the sea dissolves in the merciless sunshine, the yellow and orange spots of tiled roofs melt. Red-hot, as if glowing from the heat, the ground in the foreground is transmitted in a hot red color. Compared with the soil, even the whitewashed walls of small houses seem to be cooler, so they are painted in lilac paint.

Only a narrow strip of dark green shadow runs along the houses. The windows are painted in the same cold green paint: cool twilight reigns inside buildings. Matisse’s bold innovation lies in the fact that with the help of pure color, using his associative properties, he conveys not only light, but also heat sensations. The artist continues to solve this problem in many of his later works. The picture entered the Hermitage in 1948 from the State Museum of New Western Art in Moscow.

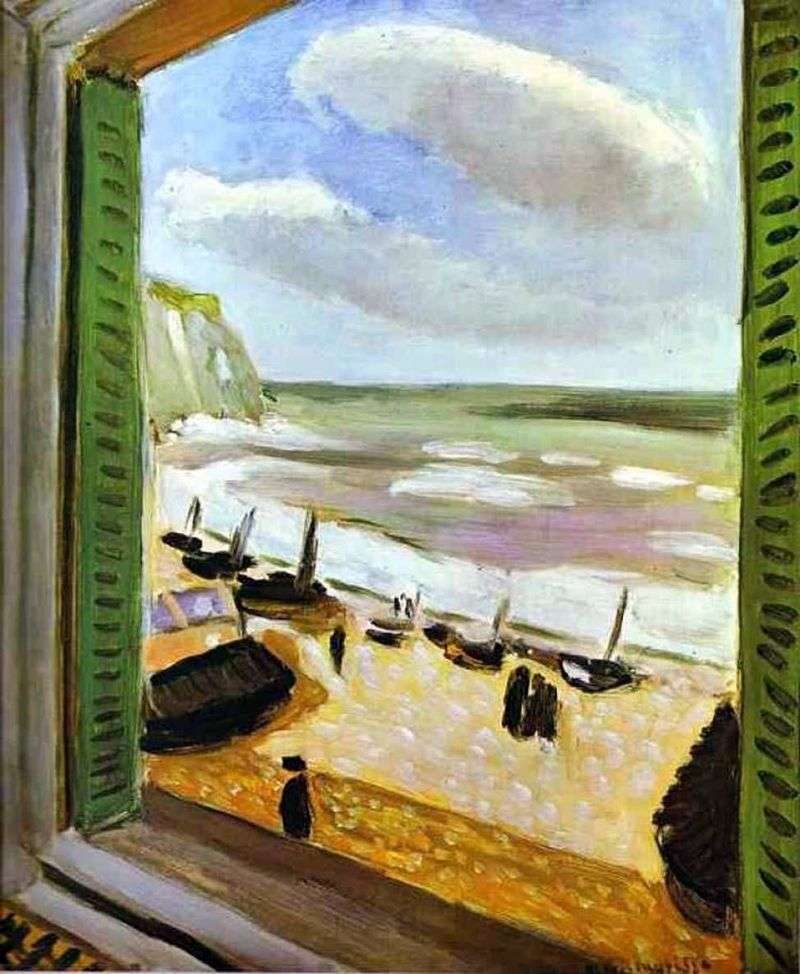

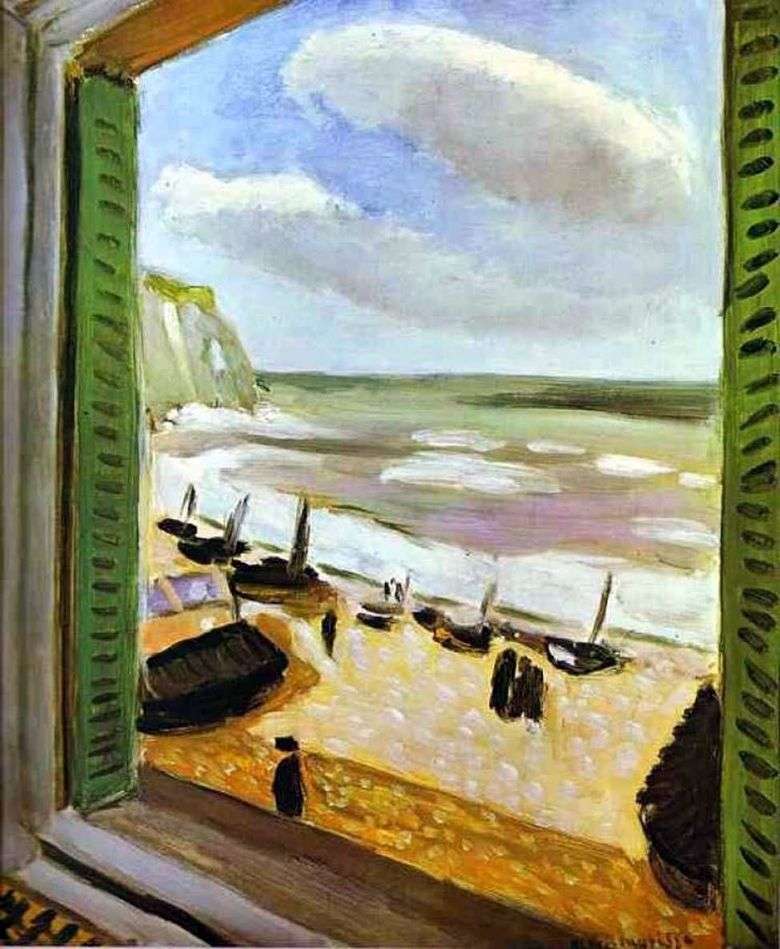

Open window in Collioure by Henri Matisse

Open window in Collioure by Henri Matisse Vue de Collioure – Henri Matisse

Vue de Collioure – Henri Matisse Dining table by Henri Matisse

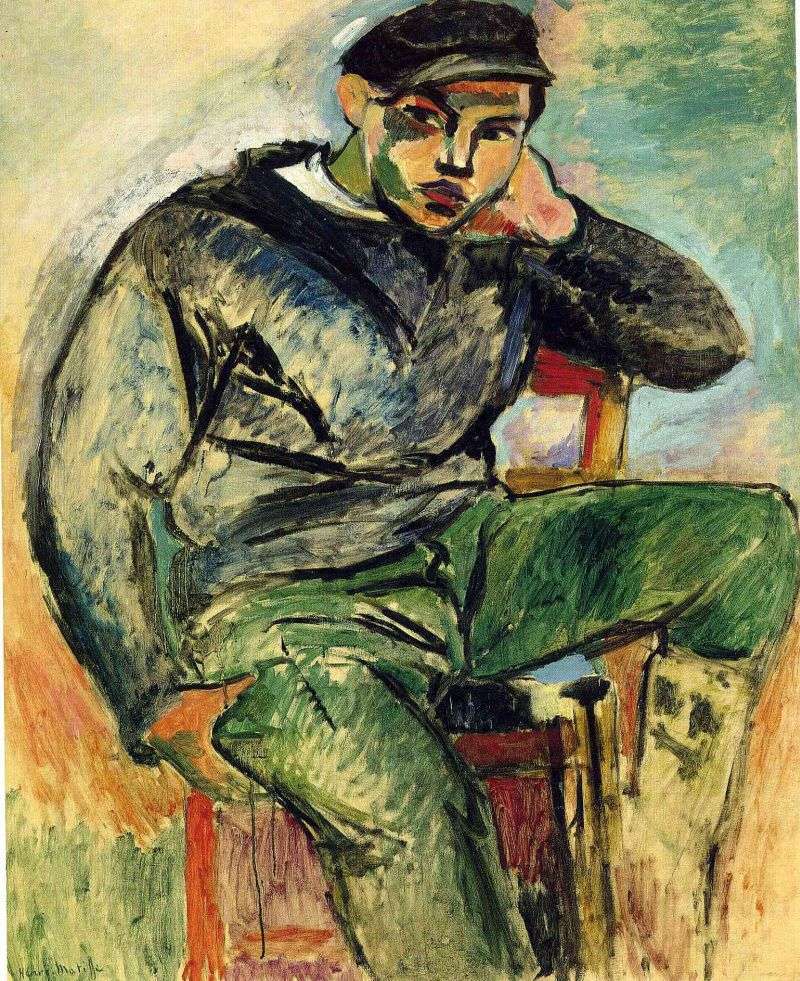

Dining table by Henri Matisse Young Sailor by Henri Matisse

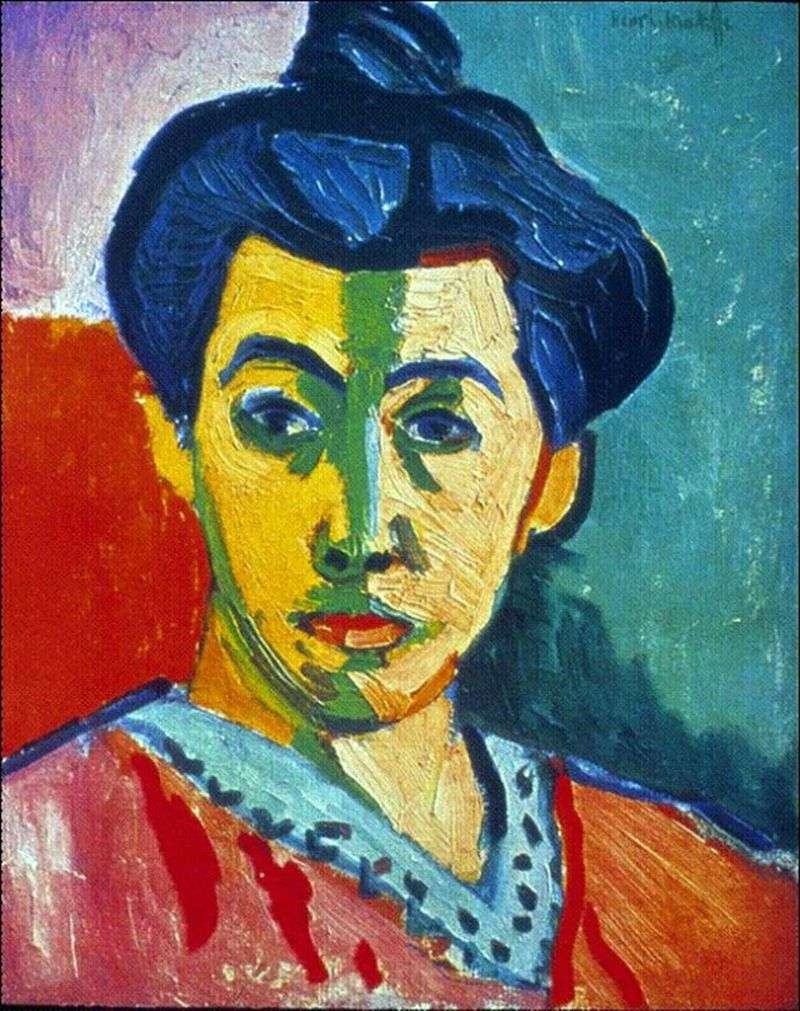

Young Sailor by Henri Matisse Madame Matisse (Green Bar) by Henri Matisse

Madame Matisse (Green Bar) by Henri Matisse Abrir ventana en Collioure – Henri Matisse

Abrir ventana en Collioure – Henri Matisse Vista de Collioure – Henri Matisse

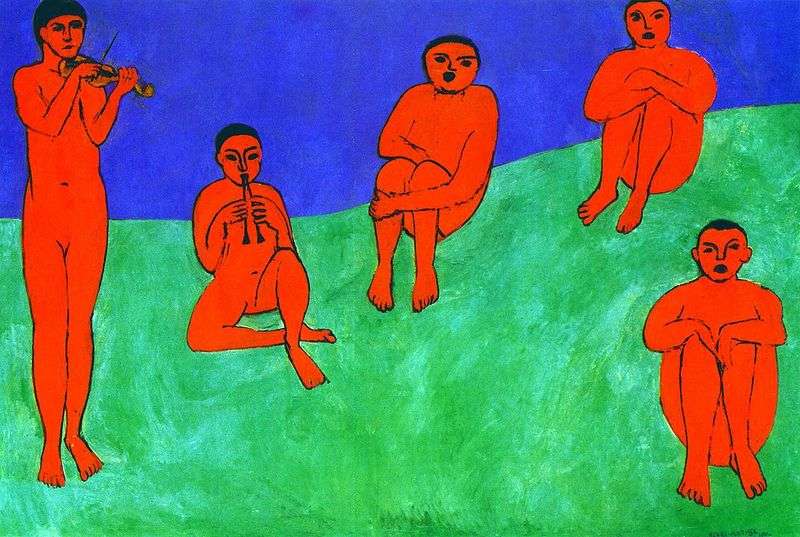

Vista de Collioure – Henri Matisse Music by Henri Matisse

Music by Henri Matisse