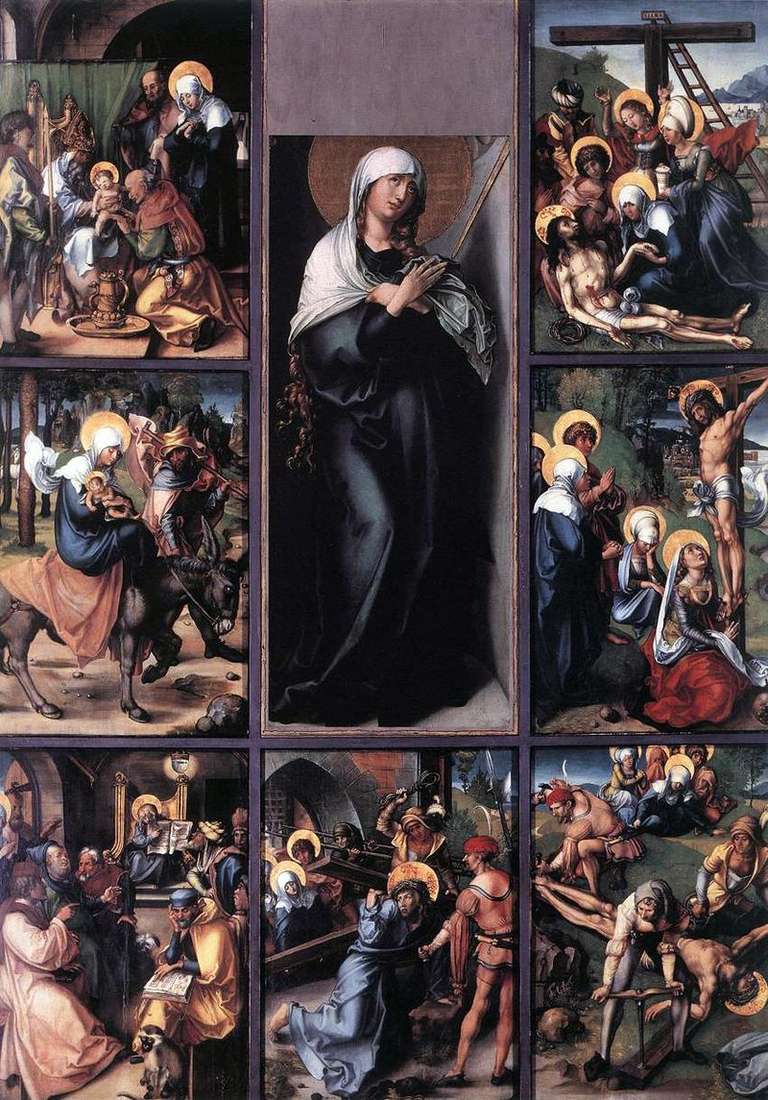

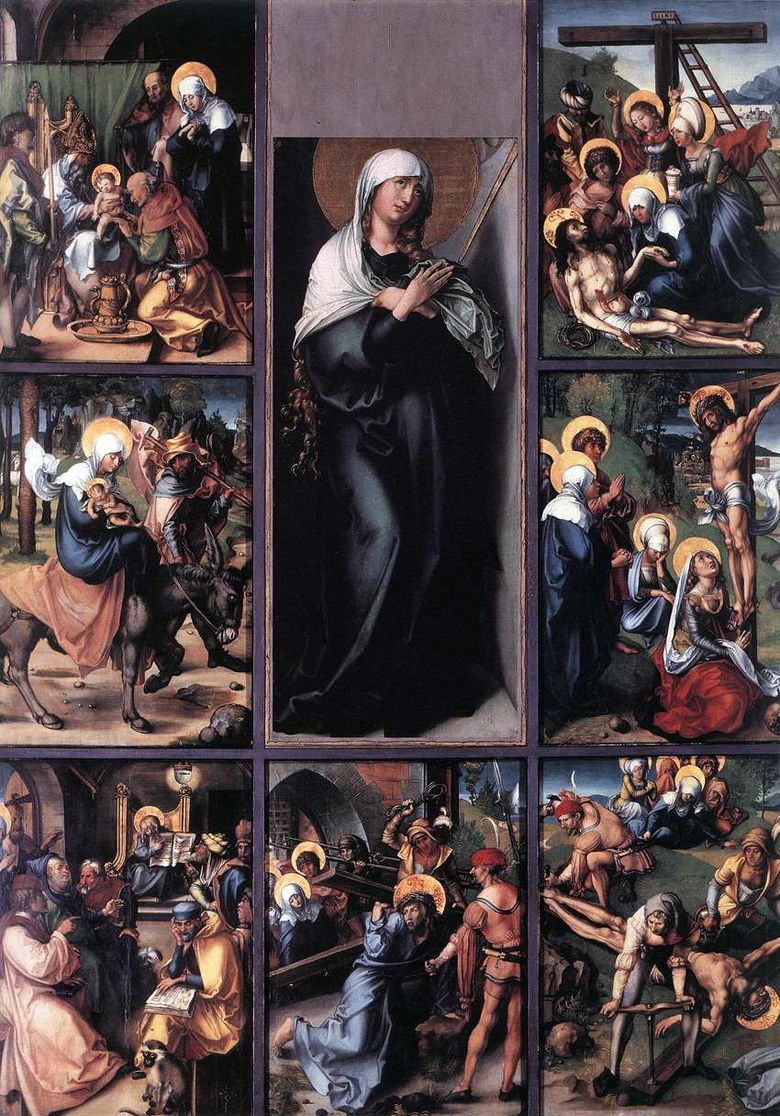

The altar of the “Seven Passions of Mary” once formed a whole and belonged to the church in Wittenberg. During the years of iconoclasm they were thrown out of the church, but, fortunately, they did not destroy it. They entered the workshop of Luke Cranach the Elder. The boards were separated from each other. Cranach ordered copies from the pictures. By their number it can be seen that initially the paintings were larger. The whole, probably, could be called “The Seven Joys and the Seven Passions of Mary”. The life of the mother, shown as joys and pains, reflecting the life of her offspring – what a human and what common plan!

Preserved seven boards of the cycle, which is called “The Seven Passions of Mary.” The work began, most likely, with “Lamentation”. In him there is the most tangible proximity to the old art. This is especially noticeable in compositional construction, where the image size corresponded to the concept, the role of the image, and not to the present correlation of parts.

Christ is disproportionately small next to those who mourn for him. But the pose of the Mother of God, the cautious movement by which she raises the hand of Christ, trying, whether her life is still alive in her son, the face of an old woman, broken by despair, is already Durer himself!

In the painting “Christ on the Cross” – Christ is just as small, crucified. His body resembles a carved wooden sculpture. But the cross is turned so that the son was directly opposite the mother. Her eyes are fixed on the already rolling eyes of her son. The meeting of their views permeates the picture. It has a great tragic power.

We do not know anything about Durer’s first assistants. The names of those who studied and worked in his studio are known from a later time. But the fact that the “Passion of Mary” artist performed with assistants, no doubt. Researchers have until now completely disagreed that these hands belong to Durer’s hand, which is written by apprentices. But he considered the whole plan of a huge, complex whole.

“Nailing to the Cross” – the most difficult and the most courageous in the cycle. From the depth of the picture to its lower edge extends a huge heavy cross, knocked together from thick beams. He lies, suppressing his weight with the earth, mercilessly crushing bushes and grass. Cross is written with extraordinary thoroughness: on the planed surface of the beams visible fibers, at the end – a section of annual tree rings. This detail gives terrifying reliability to what is happening.

On the cross, Christ thrown backwards. He threw back his head in a thorns crown. His face is deadly pale. The nimbus seems to be a cap, rested against the ground. A thin body stretched along the cross did not have enough room in the picture: the fingers of one hand and both legs go beyond its edges. Lying body with arms spread occupies most of the visible space – half the world.

Between the crucified and the audience is another figure. Bent, it still looks huge. It’s a carpenter. Without looking at the condemned man, he unperturbedly drills a hole in the cross with a borer.

The carpenter is dressed in the same way that rich German artisans dressed up on holidays. He has a dandy hat with brushes, a thin shirt with puffs, tight tricot, smart shoes. He has a young, handsome face, focused on the important matter that he was ordered to do.

The movements of the drilling hands are transmitted with utmost precision. Near the crucified man stands on his knees the second carpenter, dressed plainly, is an apprentice. He just punched the palm of Christ with a chisel, lowered the hammer and looked attentively at the body of the person being tortured. Scary look! He is curious as to what cramp in the defenseless body a hammer blows over the chisel that pierces his hand.

This is the same character who acts on the painting “Carrying the Cross.” There he assiduously lashes Christ with a rope. And in the foot of the cross a chisel is wielded by a man in a dapper coat, in a beret with an ostrich feather, with a sleek beard and a short sword on his belt. Artisans did not dress like that. It’s a nobleman. In “Carrying the Cross,” he tore the rope, forcing the fallen Christ to rise.

In the painting of Durer the executioners are not professional, but voluntary. From this they are even more terrible. Looking at their serious faces, the earnestness and diligence with which they do their villainous deed, one involuntarily thinks: Dürer through the ages foreseen the same executive and diligent, same voluntary hangmen of the 20th century who will answer the question – do they understand that They did the following: “We carried out the order”.

Dürer dressed the tormentors of Christ in the garments of his fellow tribesmen and contemporaries. And so he said: Golgotha is not somewhere and sometime. It’s here and now. Calvary everywhere, where persecuted and tortured defenseless people, where they are loaded with heavy crosses of suffering, where they are crucified; Calvary everywhere, where there are people who are willing to make these crosses, put them on foreign shoulders, punch other people’s hands and feet with nails, torment and crucify those who are given into their power.

In the paintings of this cycle, not only do compassion, pain, and pity sound. There is a perceptible blow of an angry time that is coming and threateningly calling to account those who dressed up for execution as a holiday. In these pictures, the language of future Protestant sermons is clearly heard. The pupils of the young Durer passed not only a professional but also a moral school…

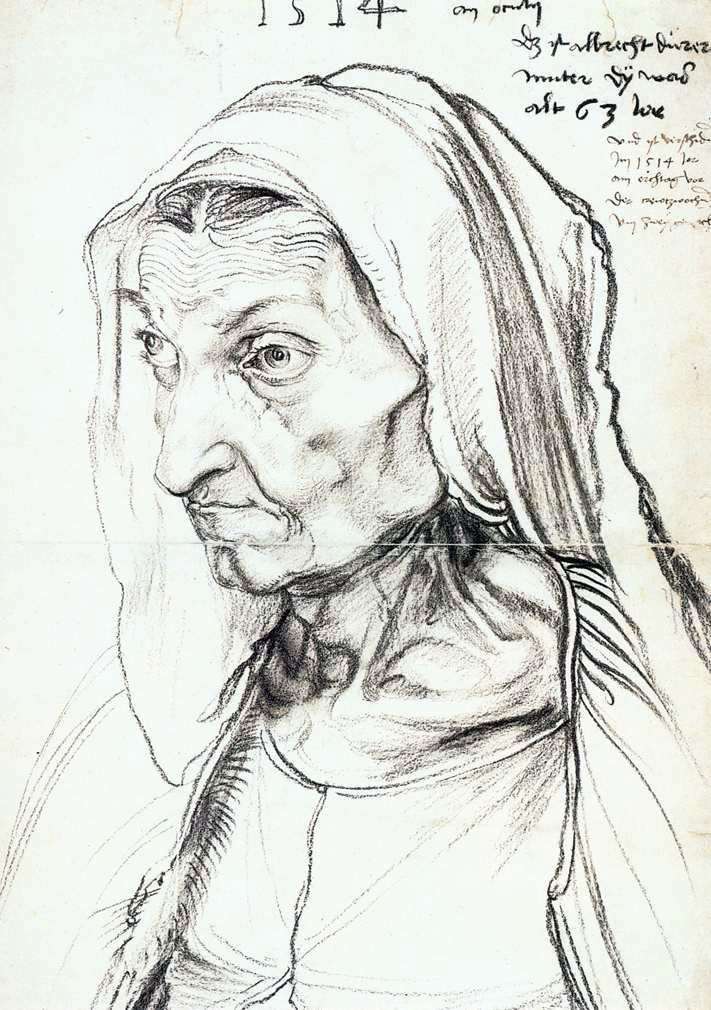

Portrait of a Mother by Albrecht Durer

Portrait of a Mother by Albrecht Durer Les sept passions de Marie – Albrecht Durer

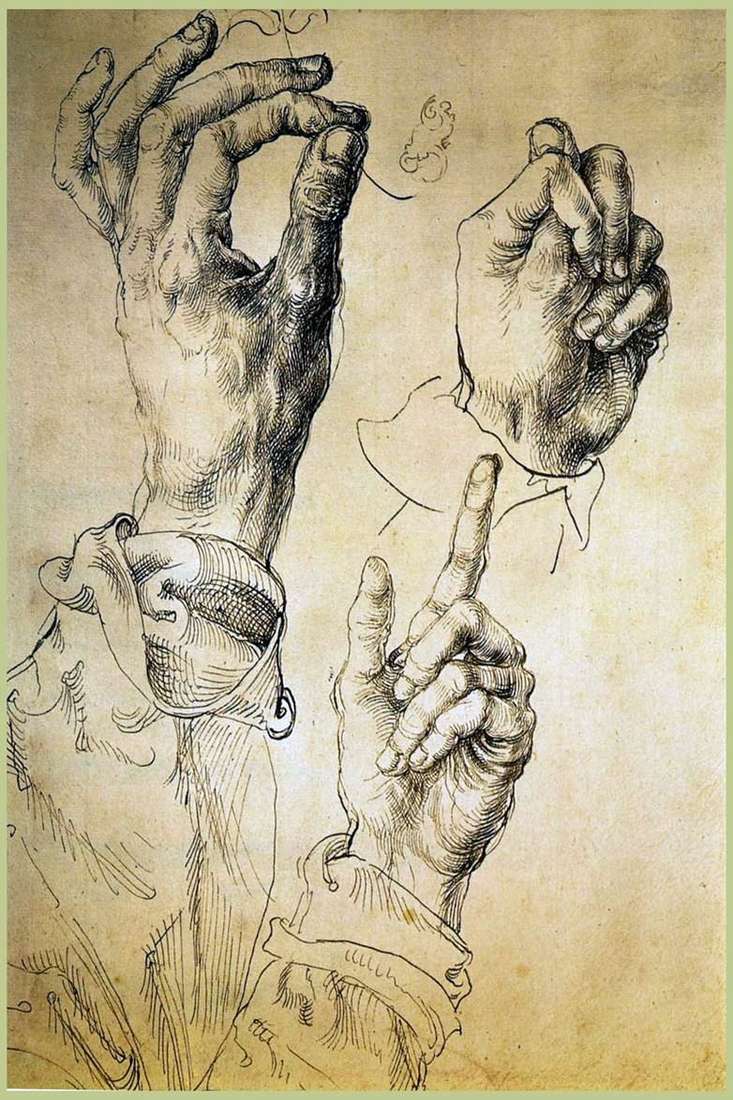

Les sept passions de Marie – Albrecht Durer Etude “Three Hands” by Albrecht Durer

Etude “Three Hands” by Albrecht Durer Portrait of the artist’s father by Albrecht Durer

Portrait of the artist’s father by Albrecht Durer Madonna and Child by Albrecht Durer

Madonna and Child by Albrecht Durer My Agnes by Albrecht Durer

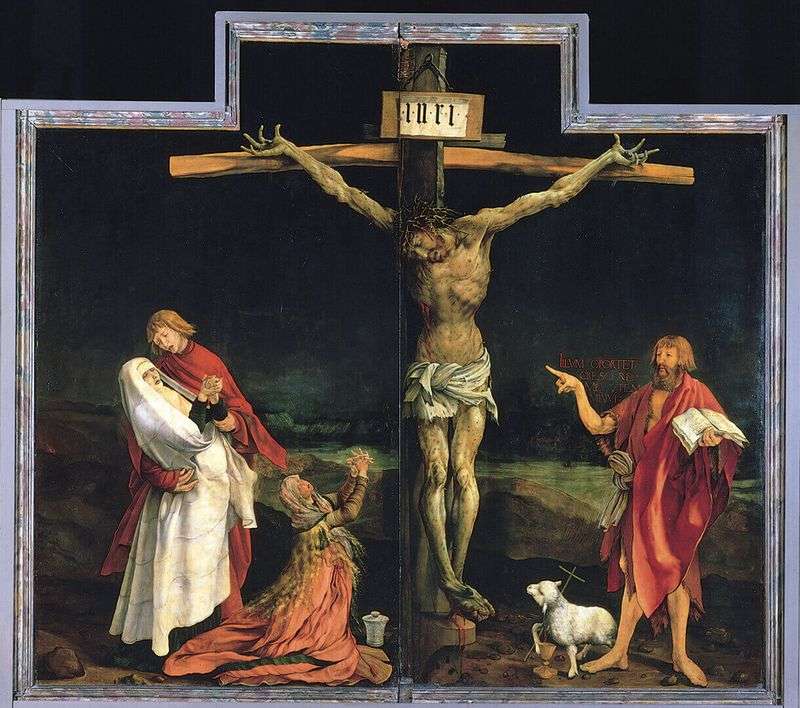

My Agnes by Albrecht Durer The Crucifixion by Matthias Grunewald

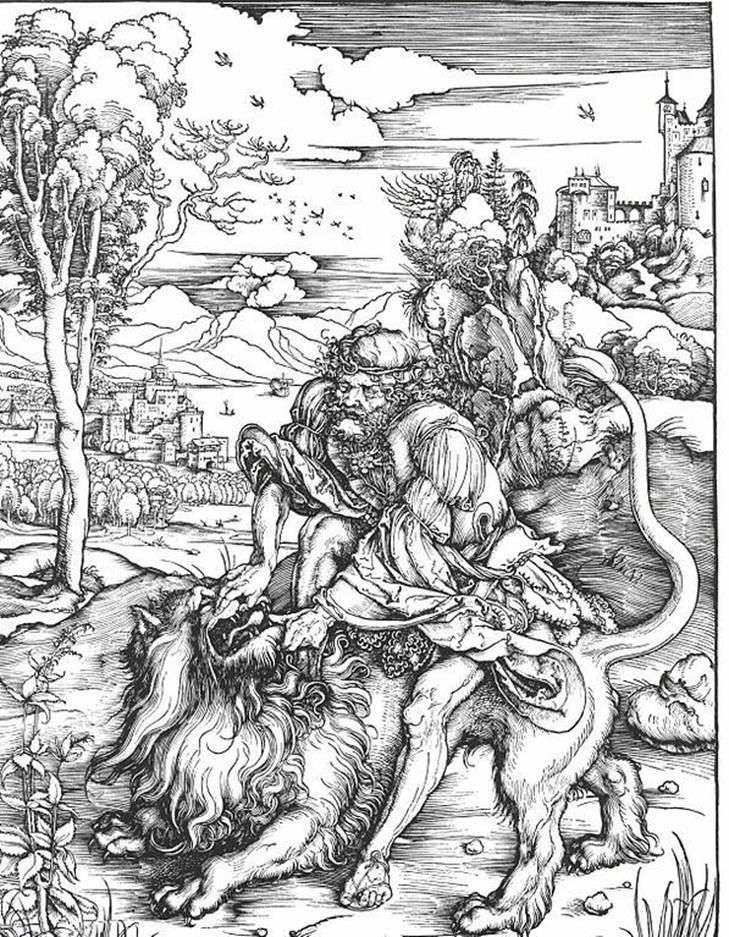

The Crucifixion by Matthias Grunewald Samson killing the lion by Albrecht Durer

Samson killing the lion by Albrecht Durer