The famous German painter Mathis Nithardt was born in Würzburg. He was a court painter, worked in Aschaffenburg, Zeligenstadt, Frankfurt am Main, in Halle. Niethardt is one of the most prominent representatives of the German Renaissance, contemporary of Albrecht Durer, Tilman Riemenschneider and Hans Holbein the Younger – the greatest German painters of the Renaissance. Such works of Nichardt as the “Weeping Angel”, “The Murder of Christ”, and, of course, the “Crucifixion”, are an integral part of the heritage of the German Renaissance.

Incredible, but true: for three hundred years this painter bore another’s name. The real name of the artist is Matis Nithardt, and Grunewald was mistakenly named by one of the biographers of the 17th century.

Despite the fact that Grunewald and Durer lived and worked at the same time, their picturesque manner and techniques are strikingly different. Only specialists are able to determine that their so different at first sight canvases were written at one time and representatives of one national culture. Unlike intellectuality, restraint in the expression of feelings peculiar to Durer, Grunewald is spontaneously emotional. If Dürer’s language is primarily a language of lines, Grünewald “speaks” the language of color.

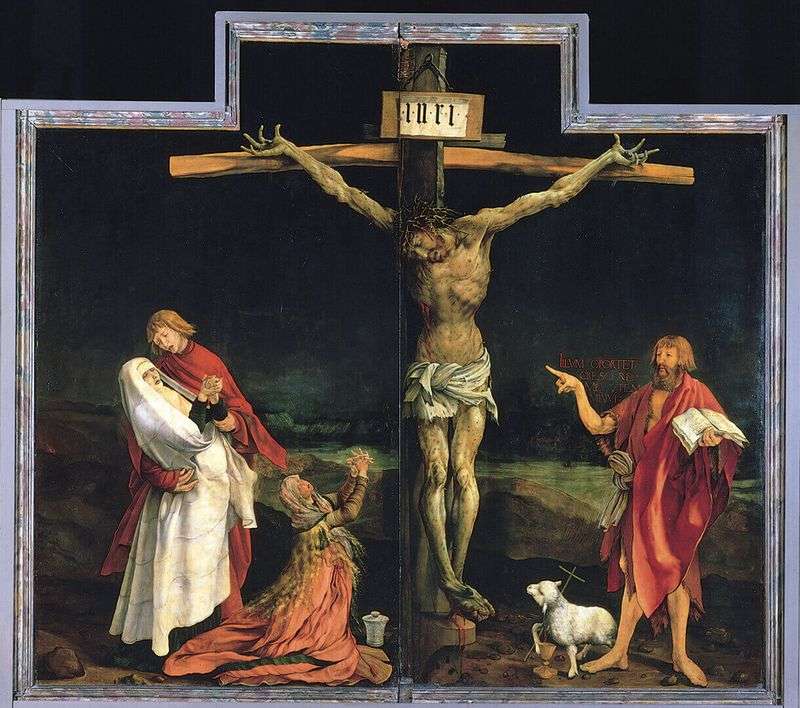

It is possible to reveal the remote similarity of the method of the German artist with the manner of the Venetians, but he does not at all resemble the pattern of images. Grunewald is cruel. The dead man in the painting “Crucifixion” – the central part of the Isenheim altar – is terrified by its realism. Figures on both sides of the cross, located in the same spatial plane with the crucified, appear smaller than they should be. This inconsistency of scale makes the picture look like an episode of a nightmare sleep: the body of a crucified person is moving from the depths to a spectator who has frozen from horror.

The impression of the nightmare is enhanced by such elements as the crooked, upstanding fingers of the crucified, the postures of John the Baptist and Mary Magdalene. Dressed in purple, John the Baptist holds a book in his left hand, and points to the body of Christ with a finger of the right. The Baptist looks nowhere; The Latin phrase, drawn by Grunewald between the right hand and the face of John, reads: “Illum oportet crescere, me autem minui,” contains the basic meaning of his teaching. The Lamb at the feet of John the Baptist miraculously holds a small cross with his right hoof.

Next to it is the cup – Holy Grail. Lamb symbolizes the spirit of Christ, meekly looking at the mortal remains of his earthly abode. In the left part of the canvas, as if divided by the Cross in two, Mary Magdalene, kneeling down, stretches out her prayerfully joined hands to Christ. Behind her, the Mother of God, with a deathly pale face from an incessant grief, falls unconscious on the hands of John the Evangelist, whose face reflects both the pain of the loss of his beloved Teacher, and the compassion of Mother’s grief.