Kuindzhi returned the landscape to an ecstatic sense of beauty and extraordinaryness of the world, refusing to poetise the prose of the slowly flowing life. Unlike the Wanderers, Kuindzhi rejected any intention to explore, replacing it with an open and frank desire to enjoy beings. Of course, the artist could not completely avoid the interpretation of life.

Nature comprehended it as part of the cosmic forces that can carry beauty. In reality, the artist was looking for an extraordinary image of the world. He tried to find it, contemplating the majestic mountain peaks, in which almost unearthly illumination is struck.

In the artist’s heritage there are many works devoted to the theme of the mountains: “Elbrus, Moonlit Night”; “Snow tops of the Caucasus Mountains”, “Snow Peak in the Caucasus”; “The top of Elbrus, consecrated by the sun”; “Elbrus in the afternoon., Herd of sheep on the slopes,” “Elbrus in the evening,” “Elbrus in the afternoon,” and many others. In some of the works, the air environment, blurring the outline of the mountain slopes, is surprisingly subtly captured.

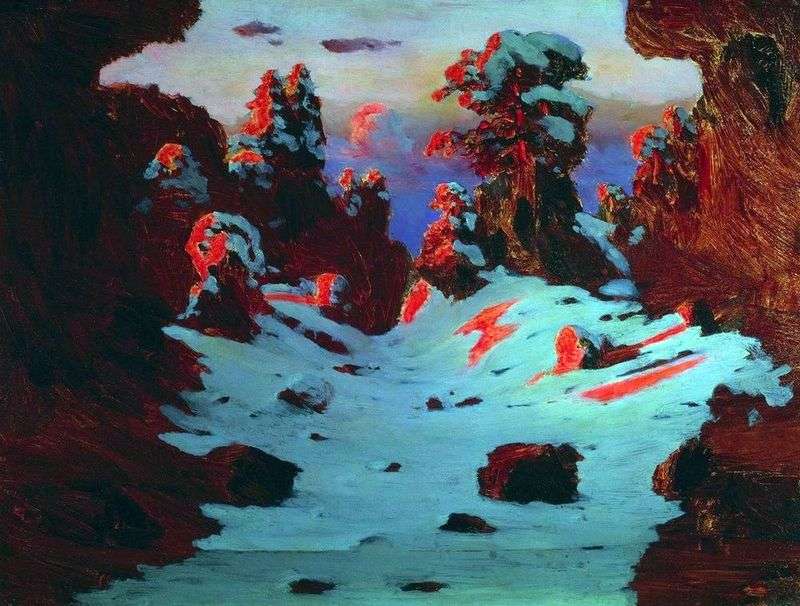

In others, it intensifies the color, so that illuminated snow peaks are illuminated by phosphorescent paints. For the first time in the Caucasus, the artist came in 1888 at the invitation of the artist Nikolai Yaroshenko, who had a dacha in Kislovodsk. The first trip was marked by a meeting with a striking phenomenon, as if foreshadowing the subsequent colorfulness of the Caucasian landscapes. In Bermamyt, Kuindzhi and Yaroshenko were fortunate enough to see the rarest phenomenon in the mountains – the Brocken ghost. On the surface of a rainbow-colored cloud, they noticed the reflection of their enlarged figures. Romantic pathos, which imbued the image of mountain ranges, shining inaccessible peaks, attracting attracting force and attracting a person to the knowledge of the unknown, grows into a symbol of the beautiful and unattainable world.

Thirty years later Kuinji’s fascination with the theme of the universe will amaze Roerich’s imagination and become his Himalayan subjects. Despite the apparent naturalism of the image, in Kuinji’s images a certain fascination with the contemplated world is clearly read. The terrestrial and the planetary merge in the integral concept of the universe. The greatness of the world fills the soul of man with a solemn sound, and the earthly one, as it were, is purified by the eternal.

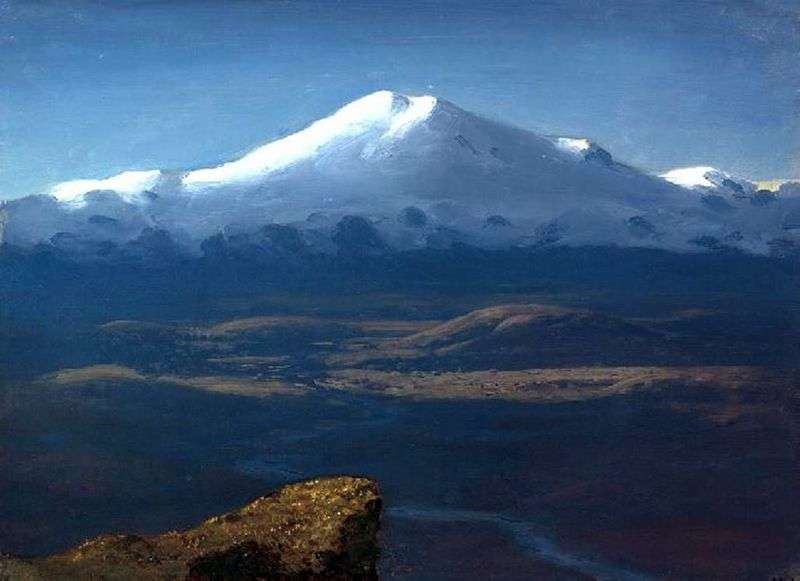

Elbrus in the evening by Arkhip Kuinji

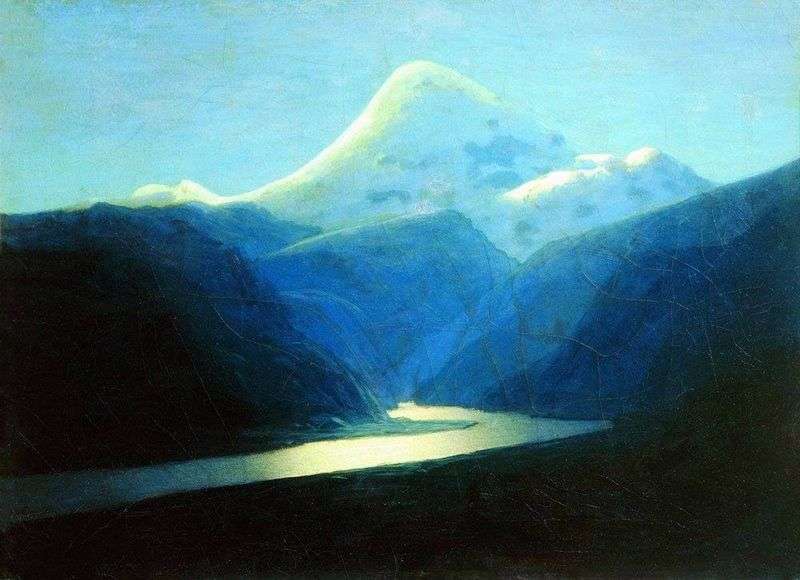

Elbrus in the evening by Arkhip Kuinji Snow Peaks – Arkhip Kuindzhi

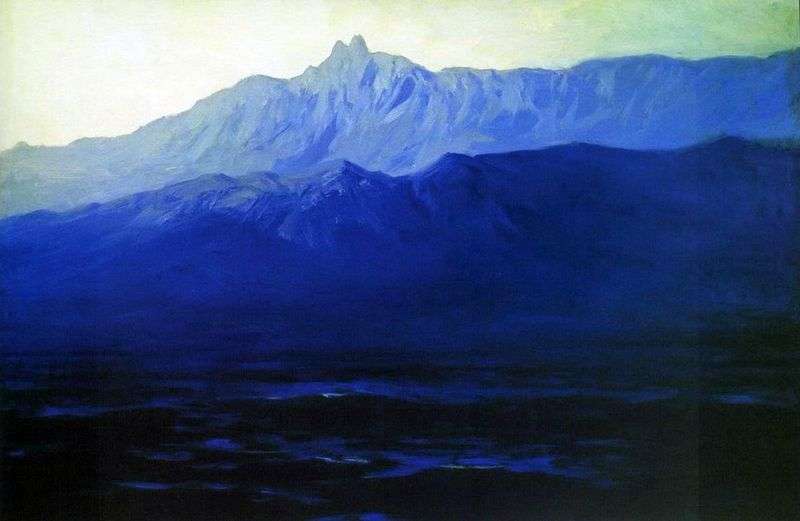

Snow Peaks – Arkhip Kuindzhi Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane by Arkhip Kuinji

Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane by Arkhip Kuinji Ai-Petri by Arkhip Kuindzhi

Ai-Petri by Arkhip Kuindzhi The sea by Arkhip Kuinji

The sea by Arkhip Kuinji Moonlit Night on the Dnieper by Arkhip Kuinji

Moonlit Night on the Dnieper by Arkhip Kuinji Sunset Effect by Arkhip Kuinji

Sunset Effect by Arkhip Kuinji The Daryal Gorge. Moonlit Night by Arkhip Kuinji

The Daryal Gorge. Moonlit Night by Arkhip Kuinji