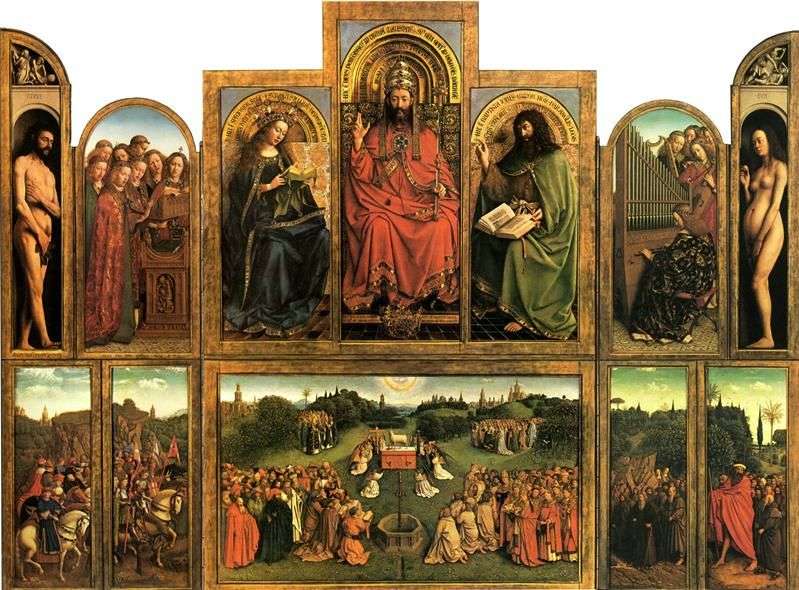

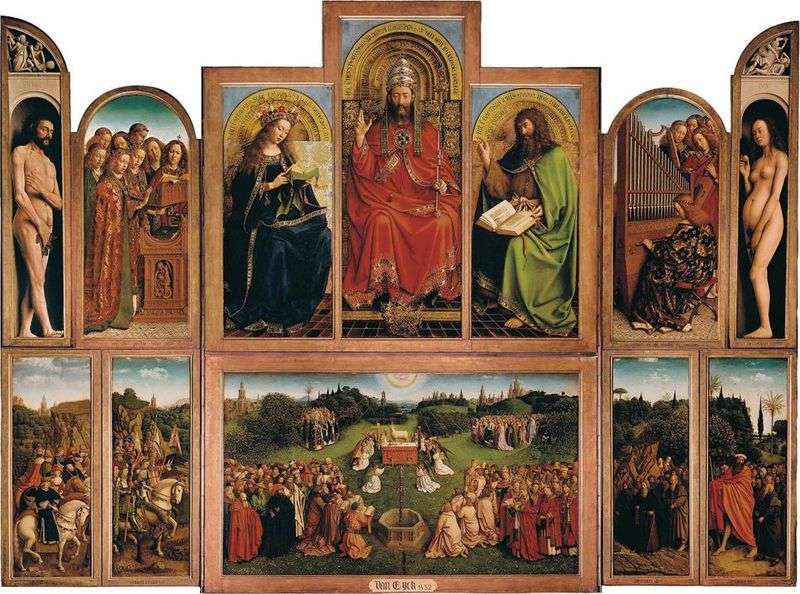

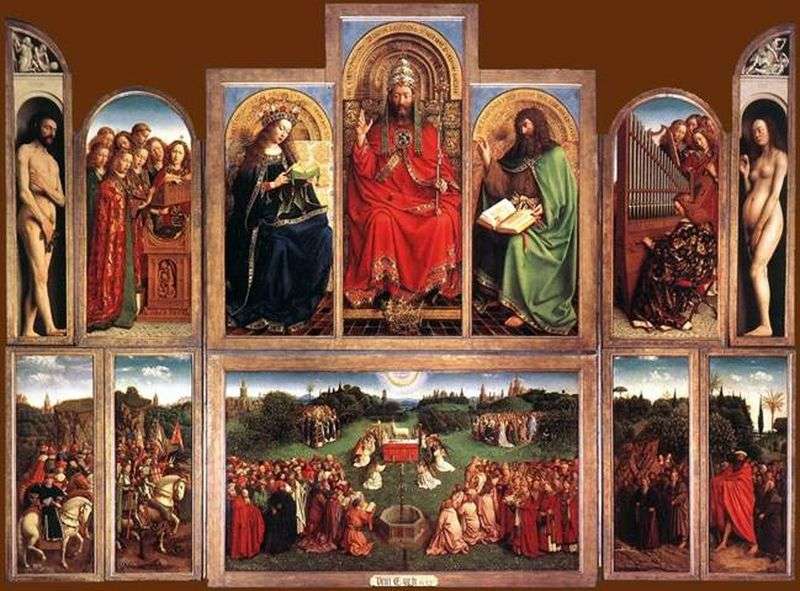

The Ghent polyptych of the brothers van Eyck is the central work of art of the northern Renaissance. This is a grandiose, multi-part structure, measuring 3,435 by 4,435 meters. The multi-leaf altar was originally intended for the side chapel of John the Baptist in Saint-Bavo in Ghent. A careful analysis of the altar made it possible to distinguish between the work of both brothers – Hubert and Jan. Having begun work Hubert died in 1426, the altar was completed in 1432 by Jan, who performed the panels that make up the outside of the altar, and to a large extent the inner sides of the side flaps.

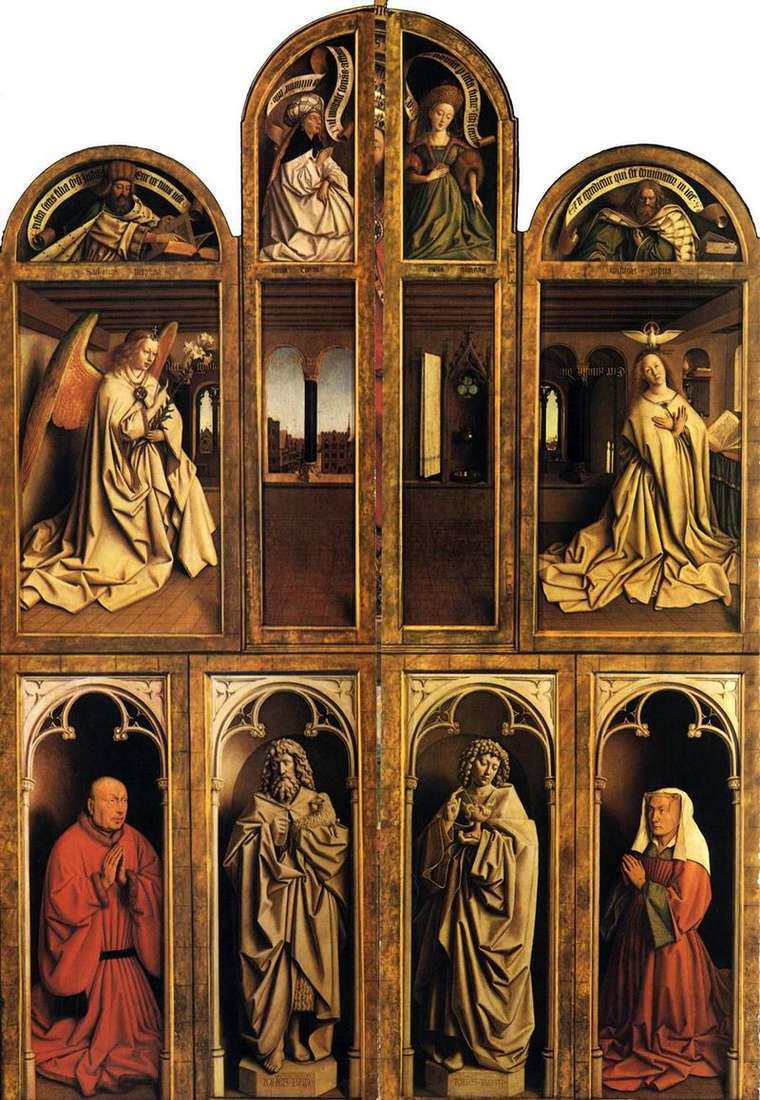

When comparing the procession on the inside of the side flaps with the scene of the lamb worship, you can see that in Jan’s work the figures are grouped more freely. Jan pays more attention to a person than Hubert. Figures written by him are more harmonious, they are more consistent, evenly reveal the precious nature of man and the world. On holidays the doors parted. The light airy scene in Maria’s room was revealed – literally and figuratively – in her very essence. The altar becomes twice as large, it acquires a broad and solemn multi-tone. It lights up with a deep color shine.

Transparent light-bearing scene of the “Annunciation” is replaced by a majestic and magnificent series of figures. They are subject to special patterns. Each figure is like an extraction, a concentration of reality. And each is subordinated to a joyous, triumphant hierarchy, led by God. It is the focus of the whole system. He is the largest, he is pushed deeper and higher, he is immovable and, unique, is turned outside the altar. His face is serious. He directs his gaze into the space, and his steady gesture is devoid of chance.

This is a blessing, but a statement of the highest necessity. He is in color – in a red burning color, which is poured everywhere, which flares up in the most hidden corners of the polyptych and only in the folds of his garments finds his highest burning. From the figure of the god-father, as from the beginning, as from the point of reference, the hierarchy is solemnly unfolding. Mary and John the Baptist, depicted beside him, are subject to him; too sublime, they are deprived of its stable symmetry. In them, plastic is not defeated by color and the infinite, deep sonority of color does not pass into intense, flaming burning. They are more material, they are not fused with the background. Next are the angels.

They are like the younger sisters of Mary. And the color in these doors fades and becomes warmer. But, as if to fill the weakened color activity, they are represented by singers. The accuracy of their mimicry makes for the viewer a visual, as it were real perceived height and transparency of the sound of their hymns. And the more powerful and material the phenomenon of Adam and Eve. Their nakedness is not simply indicated, but presented in all its evidence. They stand in growth, convex real. We see how the skin turns pink on the knees and hands of Adam, how the forms of Eve are round. Thus, the upper tier of the altar unfolds as a striking hierarchy of realities in its successive change. The lower tier, depicting the worship of the lamb, is solved in a different way and contrasted with the upper one.

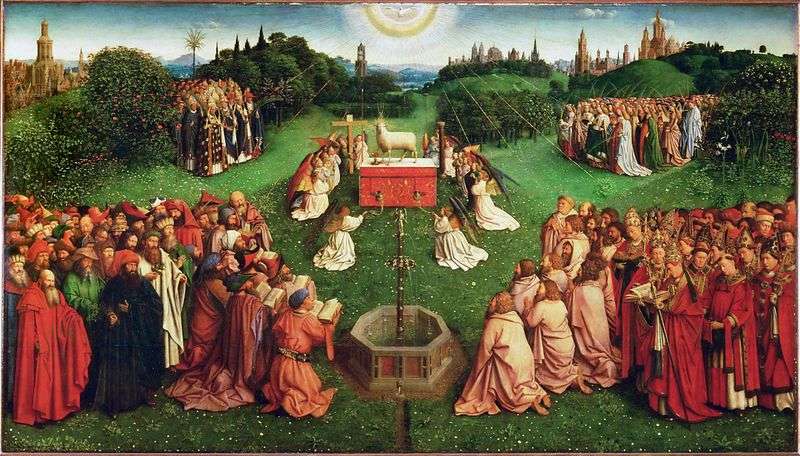

Luminous, seeming immense, it extends from the foreground, where the structure of each flower is distinguishable, to infinity, where in a free sequence the harmonious verticals of cypresses and churches alternate. This tier has panoramic properties. His heroes do not act as isolated entities, but as part of a multitude: clergymen and hermits, prophets and apostles, martyrs and holy wives gather in the procession from all over the world in a procession. In silence or with singing, they surround the sacred lamb – the symbol of the sacrificial mission of Christ.

Before us are their solemn communities, in all its beauty, the terrestrial and celestial openings open, and the landscape acquires an exciting and new meaning, more than just a distant view, it is transformed into a kind of embodiment of the universe. The lower tier represents another aspect of reality than in the upper, but they both form a unity. In combination with the spatiality of “Worship”, the color of the clothes of God the Father flames even deeper. At the same time, his grandiose figure does not suppress the environment – he rises, as if radiating from himself the beginning of beauty and reality, he crowns and embraces everything. And as the center of equilibrium, as the point that completes the entire composition, a precious openwork crown is cast under his figure, shimmering with all conceivable multicolorness. It is easy to see in the Ghent Altar the principles of miniatures of the 20s of the 15th century,

The Ghent Altar Worship of the Lamb by Jan van Eyck

The Ghent Altar Worship of the Lamb by Jan van Eyck Ghent Altar by A Kind of Open Altar – Jan van Eyck

Ghent Altar by A Kind of Open Altar – Jan van Eyck Ghent altar in the closed state by Jan van Eyck

Ghent altar in the closed state by Jan van Eyck Ghent Altarpiece by Jan and Hubert van Eyck

Ghent Altarpiece by Jan and Hubert van Eyck Stigmatization of St. Francis by Jan van Eyck

Stigmatization of St. Francis by Jan van Eyck Ghent altar in the Cathedral of St. Bavo by a kind of closed altar – Joddes Vaid

Ghent altar in the Cathedral of St. Bavo by a kind of closed altar – Joddes Vaid The altar of the Virgin Mary by Jan van Eyck

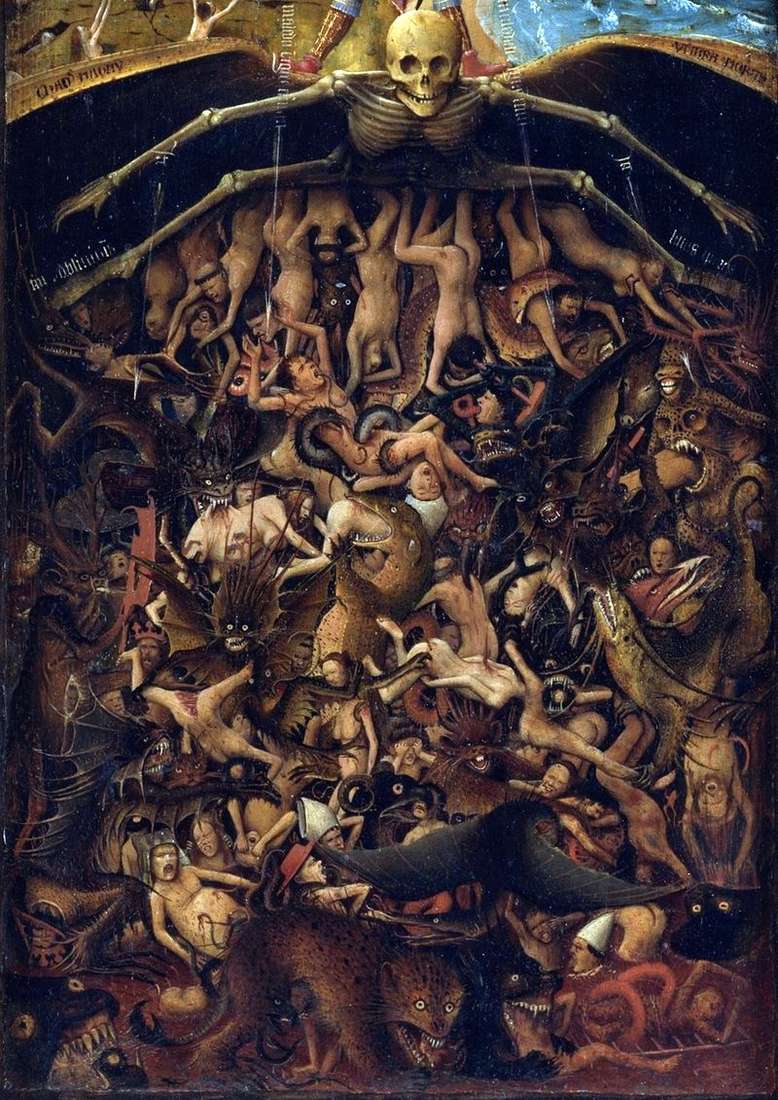

The altar of the Virgin Mary by Jan van Eyck The Last Judgment by Jan van Eyck

The Last Judgment by Jan van Eyck