In order to write “Burlakov on the Volga”, Repin took several years of hard work. He made several trips to the Volga, made friends with the future heroes of his picture, talked with them for a long time, trying to understand how these people live.

Gradually, Repin decided to change the original intention of the painting. Now he no longer tried to depict the contrast between the fun of smart young ladies and the hard work of barge haulers. The scene was moved to the Volga. Summer midday reigns in the picture: a sandy shallow is flooded with hot sun, light clouds run across the summer sky. In the background, you can see the laden barge with the figure of a clerk or master, and in the foreground – a bunch of barge haulers, who, with an effort, are pulling the ship out of the last forces.

Repin specially contrasted the magnificent colors of nature – the amber of sand, the deep blue of water, the blue expanse of the sky – to the gray, earthy colors with which the haulers were painted. Eleven people in dirty tatters, soaked through with salty sweat, in rotten bast shoes or onches personify hard work, which at that time was valued even lower than horse.

Repinsky barge haulers do not sing, sullenly leaning on the straps, they do not say a word, but the whole picture is like a groan of the Russian people, poor and destitute. Repina’s haulers are a gallery of bright personalities specially selected by him. Each of them has an individuality, character, inner world, biography, psychology and its own attitude to life.

Ahead are the “rootstocks.” – The strongest and most experienced barge haulers. The first is pop-defrocking, who has already seen everything in his lifetime, next to him is a kinked barge, overgrown with a beard right up to the eyes. Left and slightly behind the priest – Ilka-sailor. His head is tied with a rag, and the attentive gaze of the eyes glittering with whites is directed straight at the viewer. Behind Ilkoy is a tall, thin barge with a pipe in his mouth. Repin portrayed him as unkind, embittered.

In the second group, the viewer’s eye falls primarily on a tall, young boy in rags of a red shirt. He slowed his pace a little, straightening the strap, and his figure stood a-la across the movement of the barge haulers.

To his right is a thin, emaciated barge hauler, who, utterly exhausted, wipes his wet forehead with his sleeve, to the left is an old man, who must have repeatedly passed the Volga up and down. The retired soldier in the cap, pulled down over his eyes, is a tall soldier turned to the viewer in profile, and a little man who literally hung on the strap. Such strong, bright and whole characters cannot be simply invented, they had to be first found, understood and only then written. “Barge haulers on the Volga” became the first picture of Repin from those canvases that showed true Russia of that time.

Wandering haulers by Ilya Repin

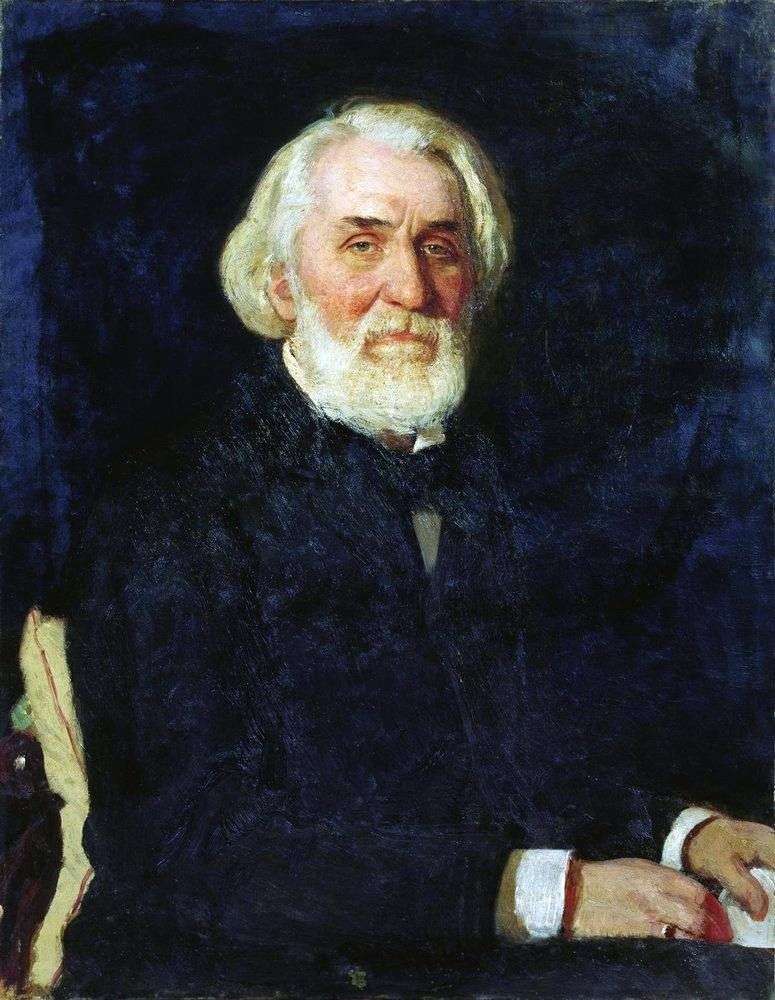

Wandering haulers by Ilya Repin Turgenev by Ilya Repin

Turgenev by Ilya Repin Seeing a Recruit by Ilya Repin

Seeing a Recruit by Ilya Repin Los vagabundos errantes – Ilya Repin

Los vagabundos errantes – Ilya Repin Transporteurs de barges sur la Volga – Ilya Repin

Transporteurs de barges sur la Volga – Ilya Repin Transportes de barcazas en el Volga – Ilya Repin

Transportes de barcazas en el Volga – Ilya Repin Vera Repin on the bridge in Abramtsevo by Ilya Repin

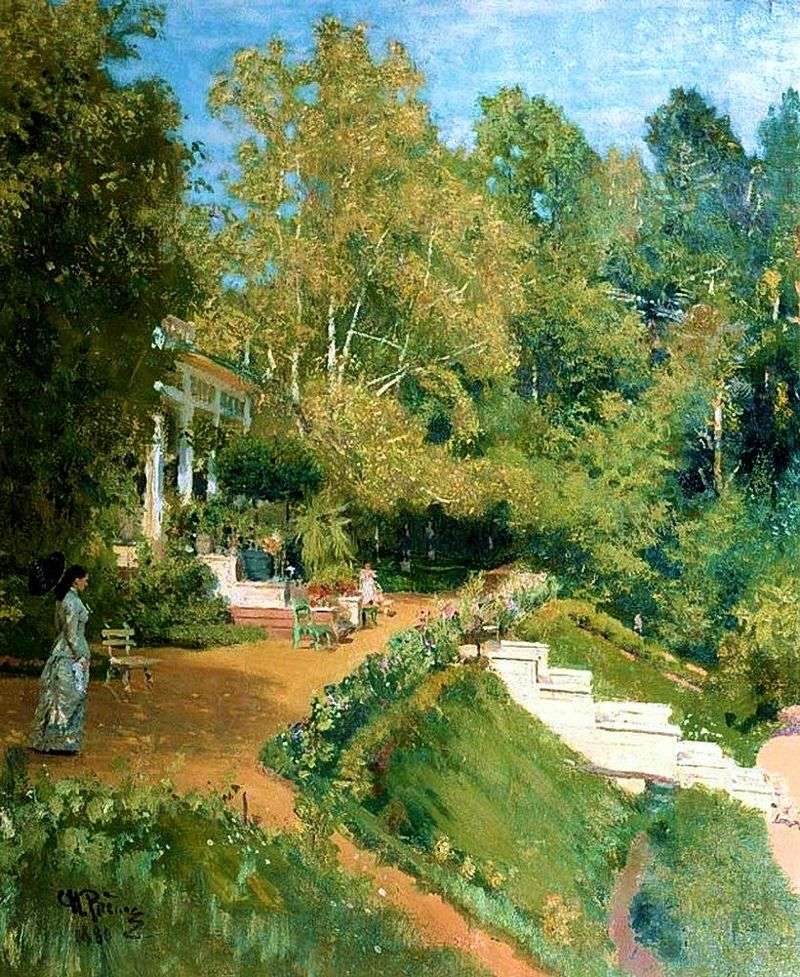

Vera Repin on the bridge in Abramtsevo by Ilya Repin Abramtsevo. Summer landscape by Ilya Repin

Abramtsevo. Summer landscape by Ilya Repin