Two musicians are a flutist and a drummer. Both – especially the drummer – are young and cheerful. With dashing carelessness, the drummer threw a raincoat, cocked his head defiantly, beats the drum with enthusiasm. In a carefree musician, we easily, though with surprise, recognize Durer. He knew and saw himself and such. And he loved this state of his. “He did not at all think that the sweetness and fun of life are incompatible with honor and decency, and he himself did not neglect them,” his contemporary and scholar Joachim Camerari, in a foreword to the treatise of Durer, will write about him with insight.

The landscape, against which the musicians are depicted, breathes with joy and lightness: a blue sky in transparent clouds, blue mountains on the horizon, a sunlit green meadow. Color bright, sonorous, like the melody of a flute… Durer could write himself a prophet, but could “idle the idle” and convince the viewer in both cases: “I am like that!” Durer was not deceived about himself. And did not deceive. He was and such and such. One of the properties of genius is the ability to live in different, often contradictory states of mind. And in each of them be convincing.

Hands of the worshiper by Albrecht Durer

Hands of the worshiper by Albrecht Durer Portrait of Jakob Muffel by Albrecht Durer

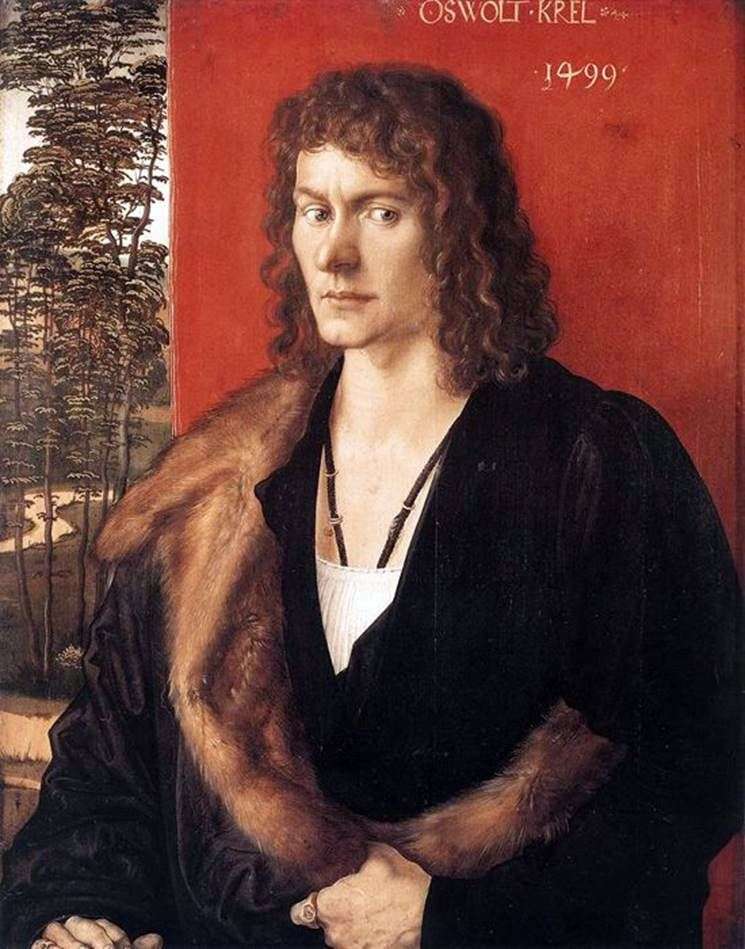

Portrait of Jakob Muffel by Albrecht Durer Portrait of Oswald Krell by Albrecht Durer

Portrait of Oswald Krell by Albrecht Durer Madonna and siskin by Albrecht Durer

Madonna and siskin by Albrecht Durer Portrait of Barbara Durer by Albrecht Durer

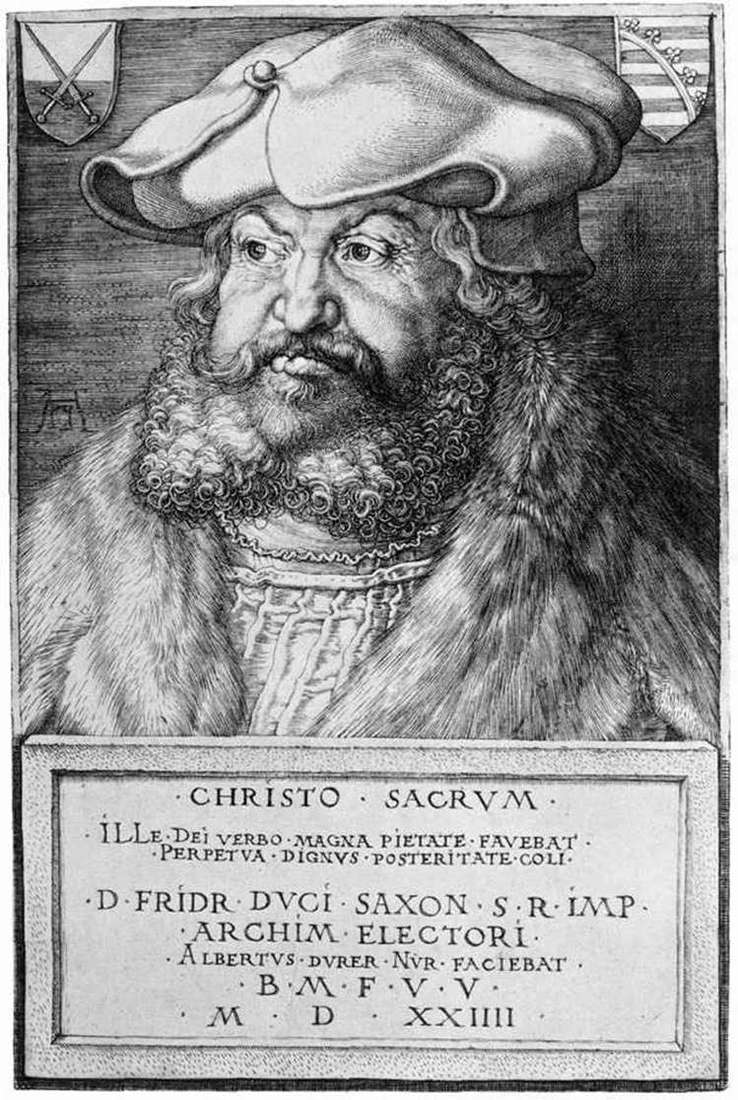

Portrait of Barbara Durer by Albrecht Durer Portrait of Friedrich the Wise by Albrecht Durer

Portrait of Friedrich the Wise by Albrecht Durer Portrait of the artist’s father by Albrecht Durer

Portrait of the artist’s father by Albrecht Durer Portrait of a young Venetian by Albrecht Durer

Portrait of a young Venetian by Albrecht Durer