The first large commissioned work of Cranach, which arose in 1506 for the palace church of Wittenberg after its relocation in 1505 to the residence of the Electors of that time, Wittenberg, was the “Altar of St. Catherine,” almost trellised decorative riches and colorful splendor.

The altar of Catherine was commissioned by Cranach not accidentally: in 1502 a university was founded in Wittenberg, in which later Luther was also taught; Catherine was considered the patroness of scientists; according to legend, she converted fifty pagan professors who wanted to reject her from this faith. Later, she had to be a wheel, but after hearing her prayers, the sky sent fire, which destroyed the wheel, after which Catherine was beheaded.

Among the depicted viewers, portraits of professors of the University of Vienna are supposed to be portraits, and to the left at the top there are the Elector Frederick the Wise, to his right, near his brother Johann Constant. On the side flaps are depicted three female figures of the saints, to the left are Dorotea, Inesa and Kunigunde, to the right – Varvara, Ursula and Margarita. The reverse sides of the wings were also painted, here were placed two figures of female saints.

In the fortress, in the background of the middle board, Hartenfels Castle is supposed to be in Torgau, and in the fortress of the right tower – the fortification of Coburg, both belonged to the Saxon Elector during the Cranach times. Clearly there is a change in style, which happened at the time in the work of Cranach. His arisen paintings in Vienna foreshadowed the style of the Danube school, which later represented Altdorfer and Guber, Wittenberg’s works of Cranach were more schematic, less expressive.

“The altar of St. Catherine” is close to the early works, it goes back to them with its individual moments, like a tree on the left leaf, but it defines a stylistic transition to fine-liner decorativeness. The formulation of this topic marks the traces of Cranach’s study of one of Dürer’s wood engravings, which emerged around 1497, which testifies not to the dependence, but rather to the independence of the achievements of Cranach.

Altar de los sts. Catherine – Lucas Cranach

Altar de los sts. Catherine – Lucas Cranach Portrait of Martin Luther in the image of the knight of Jorg by Lucas Cranach

Portrait of Martin Luther in the image of the knight of Jorg by Lucas Cranach Dr. Johann Cuspinian by Lucas Cranach

Dr. Johann Cuspinian by Lucas Cranach Autel de Saint Catherine – Lucas Cranach

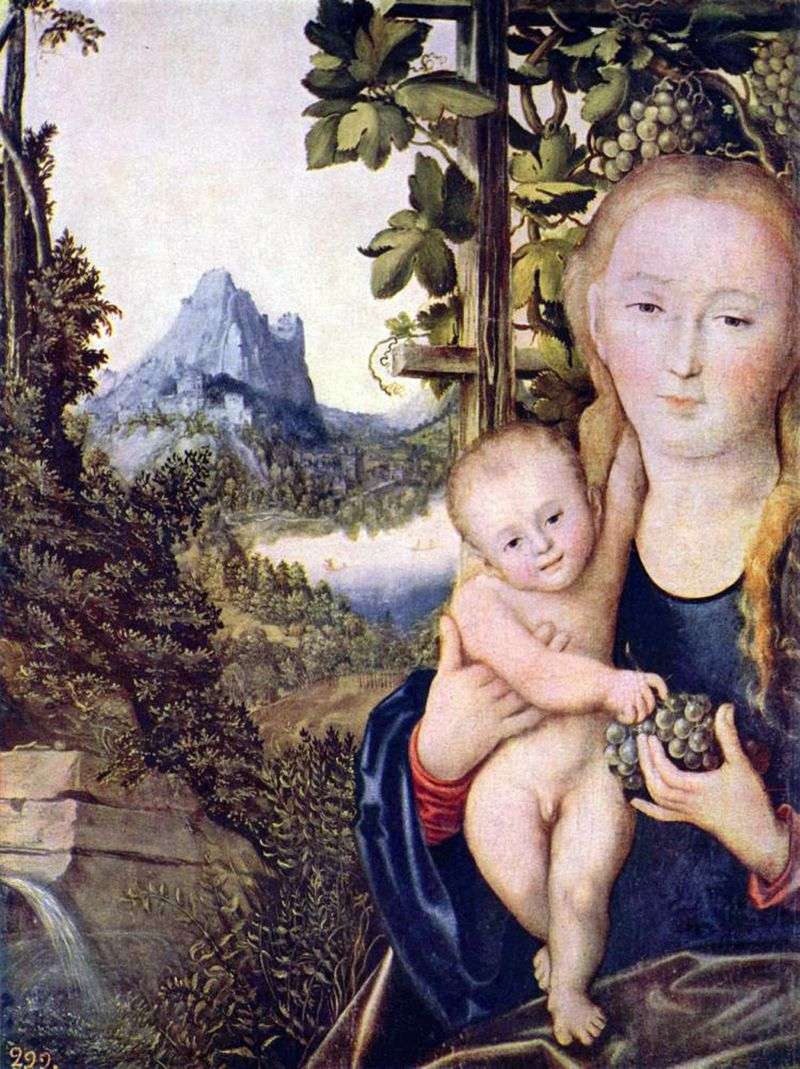

Autel de Saint Catherine – Lucas Cranach Madonna and Child by Lucas Cranach

Madonna and Child by Lucas Cranach Martyrdom of St. Catherine by Lucas Cranach

Martyrdom of St. Catherine by Lucas Cranach Portrait of a Woman by Lucas Cranach

Portrait of a Woman by Lucas Cranach Portrait of Cardinal Albrecht of Brandenburg by Lucas Cranach

Portrait of Cardinal Albrecht of Brandenburg by Lucas Cranach