The painting of the Spanish painter El Greco “Saint Francis in ecstasy”. The size of the picture is 147 x 105 cm, canvas, oil. Francis of Assisi is a saint, the founder of the Franciscan order named after him. St. Francis marks a turning point in the history of the ascetic ideal, and therefore a new era in the history of Western monasticism, the Roman curia and the humanitarian worldview.

The old monasticism, in its renunciation of the world, imposed a vow of poverty on a separate monk, but this did not prevent the monasteries from becoming large landowners, and the abbots to compete in riches and luxury with bishops and princes. Saint Francis deepened the idea of poverty: from the negative sign of renunciation of the world, he elevated it to a positive, vital ideal that stemmed from the idea of following the example of a poor Christ.

At the same time, Francis of Assisi transformed the very purpose of monasticism, replacing the monk-hermit with a missionary apostle, who, having renounced himself internally from the world, remains in the world to call on people to peace and repentance among him. In 1224, Francis went to the high peak of Mount Alverno, in the upper Arno, where he spent time, away from the brothers in the order, in fasting and solitary prayer. Here on the morning of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross, Francis had a vision, after which on his hands and feet, according to tradition, stigmata remained, ie, the images of the heads and ends of the nails of the crucified Christ.

Critical historians give a different explanation to the news of stigmata. Gaza, bearing in mind that for the first time the stigmata became known from the district letter of the successor of Francis, Ilya, considers him the culprit of the legend. Gausrath believes that Francis, wishing to survive the passions of the Christ, wounded himself, hiding them from his comrades during his lifetime.

Sabatier, considering stigmata as a real fact, is looking for an explanation in the mysterious manifestations of ecstasy and “spiritual pathology.” The narrative of the vision and stigmata of Francis greatly contributed to the idea of a later painting, depicting him in ecstasy and suffering on his face.

Despite the fact that Francis really considered his calling “to mourn the suffering of Christ all over the world” and despite his own severe suffering in the last two years of his life, Francis kept his poetic view of the world to the end. His brotherly love for every creature is the basis of his poetry. He feeds the bees with honey and wine in the winter, lifts worms from the road so that they are not crushed, redeems the lamb being led to the slaughterhouse, releases the rabbit trapped in the trap, addresses the birds in the field, asks “brother fire” when they do it to him cauterization, do not cause him too much pain.

The whole world, with all living creatures and elements in it, turned for Francis into a loving family, descended from one father and united in love for him. This image was the source from which his poetic “praise” to the Lord resulted, with all His creations and, above all, with his brother the sun, etc.,

Other poetic souls among the brethren – Foma from Celano, Jacopone from Todi, the author of “Stabat Mater”, and other Franciscan poets, joyfully responded to the call of Francis. It is exaggerated, of course, to consider Francis of Assisi, as Tode does, the creator of Italian poetry and art and the culprit of the Renaissance; but we can not but admit that the inspiration and the uplifting of the spirit, manifested in Franciscan cathedrals and Giotto’s frescoes, were inspired by the humble and loving follower of the beggar Christ. One side of his ideal – the succession of the mendicant, wandering Christ – Francis adhered to the ascetic, medieval, uncultured ideal; but in the succession of Christ, as he understood Francis, the love for man was included. B

Due to this, the ascetic ideal received a new, cultural purpose. “The Lord called us not so much for our salvation as for the salvation of many,” was Francis’s motto. If in his ideal, as in the previous monastic, and includes renunciation of the world, from earthly goods and personal happiness, this renunciation is accompanied not by contempt for the world, not by the fastidious alienation from the fallen and fallen man, but by pity for peace and compassion for poverty and the needs of man. Do not escape from the world becomes the task of an ascetic, but a return to the world for the service of man. It is not the contemplation of the ideal divine kingdom in the heavenly heights that constitutes the vocation of a monk, but the preaching of peace and love, for the establishment and realization of the kingdom of God on earth. In the person of Francis of Assisi, the ascetic ideal of the Middle Ages assumes a humanitarian character and extends a hand to the humanism of the new time. Francis of Assisi died on October 4, 1226; already two years later he was canonized by Pope Gregory IX.

Ecstasy of St. Francis by Giovanni Bellini

Ecstasy of St. Francis by Giovanni Bellini The Bliss of St. Francis by Michelangelo Merisi and Caravaggio

The Bliss of St. Francis by Michelangelo Merisi and Caravaggio Stigmatization of St. Francis by El Greco

Stigmatization of St. Francis by El Greco Saint Francis and the Angel by Guido Reni

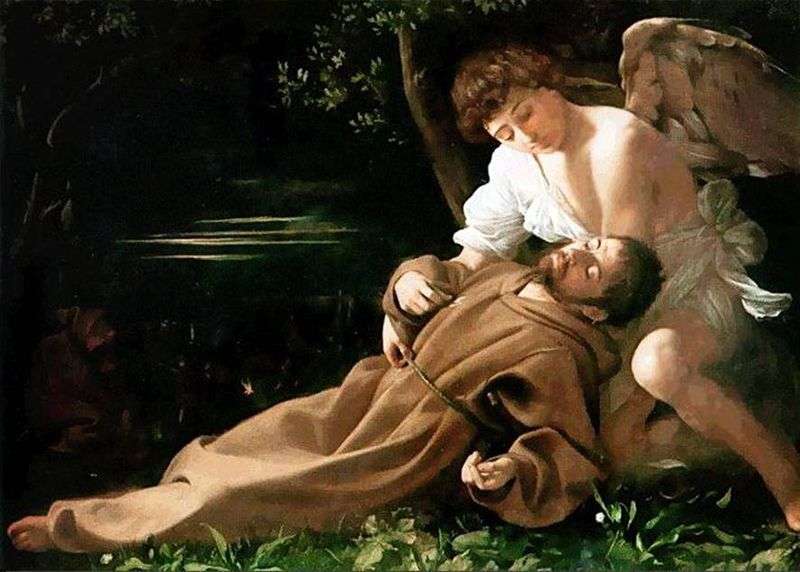

Saint Francis and the Angel by Guido Reni The ecstasy of St. Francis by Michelangelo Merisi and Caravaggio

The ecstasy of St. Francis by Michelangelo Merisi and Caravaggio St. Francis receiving stigmata, with three scenes from the life by Giotto di Bondone

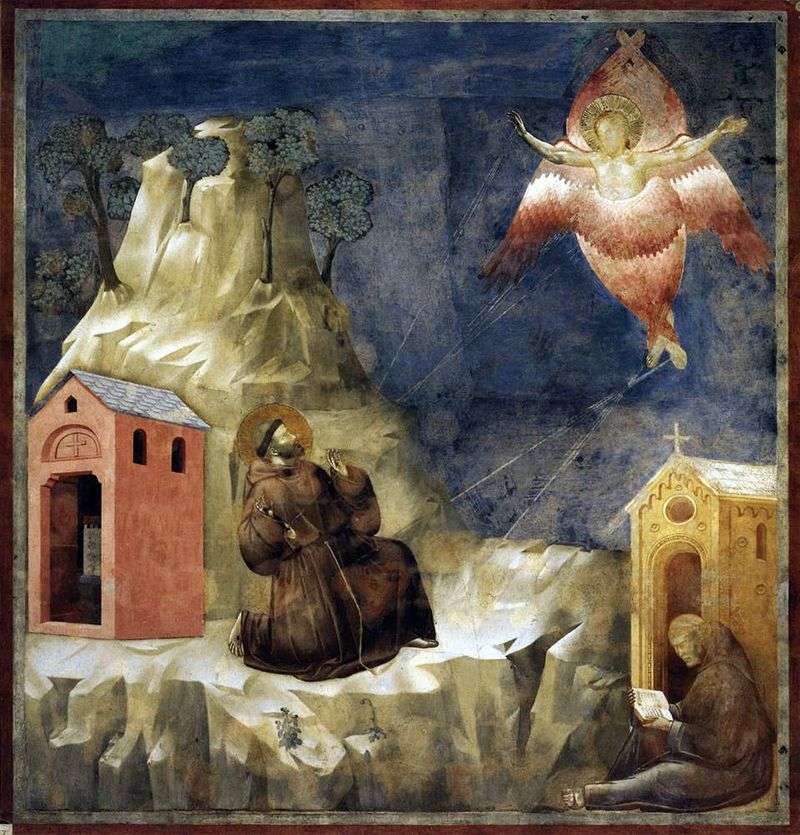

St. Francis receiving stigmata, with three scenes from the life by Giotto di Bondone St. John the Evangelist and Saint Francis of Assisi by El Greco

St. John the Evangelist and Saint Francis of Assisi by El Greco Stigmatization of St. Francis by Giotto

Stigmatization of St. Francis by Giotto