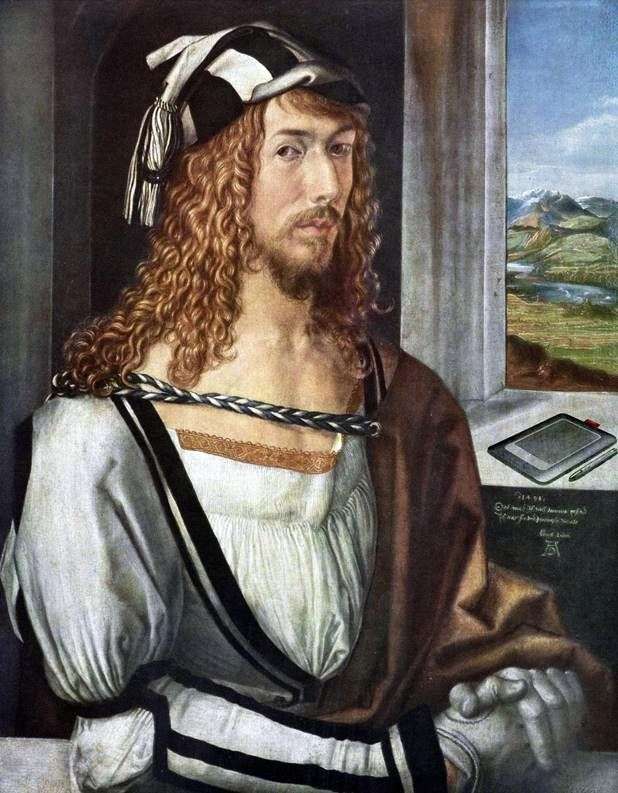

This “self-portrait” of Durer – a vivid evidence of his concern about the assertion of the social status of the artist. Carefully written details of the costume show us the incomparable ability of the author to convey the smallest details of the world around him and make us recall his own words: “The more accurately the artist depicts life, the better his picture looks.” Durer’s hands are stacked as if they are on a table. At the same time they are covered with gloves – obviously, in order to emphasize that these are not the hands of a simple artisan.

The alpine landscape opening in the window reminds of a trip to Italy, held several years earlier. Everything here works to strengthen a certain pathos; the picture proclaims the social significance of the painter, his right to inner freedom and his own view of the world. In the time of Durer, this approach was innovative. The first in the history of German painting Durer began to write self-portraits. This was a bold step, marking the liberation of the artist’s personality from the power of class prejudices. Self-portraits of Durer form a unique series. Before Rembrandt in Western European painting, something like this no one else did.

The first self-portrait the artist created at the age of thirteen. The boy in this picture has puffy lips, smoothly outlined cheeks, but not childlike eyes. In the view there is some strangeness: it seems that it is turned inside of itself. The early self-portraits of the artist are perfectly complemented by the lines from his youthful diary: “Too lazy must be the mind, if it does not dare to discover something new, but constantly moves in the old rut, imitates others and does not have the strength to look into the distance.” This attitude of young Durer to life and creativity will be preserved in him forever. In a similar vein, he decided and very chambered “self-portrait with a carnation.”

In the masterpiece of 1498, which became the theme of this section, the Renaissance approach to interpreting the personality of the artist was reflected, which should henceforth be viewed not as a modest craftsman, but as a person with a high public status. But there is one more self-portrait of Durer, where all these tendencies culminate. It dates back to the year 1500. The master wrote himself as he wanted to see, reflecting on the artist’s great vocation. A man who gave his life to the service of beauty, should be beautiful and himself. Therefore, Durer wrote himself here in the image of Christ.

It may seem blasphemy to the modern viewer. But the Germans of the beginning of the XVI century perceived everything differently: for them Christ was the ideal of man, and therefore every Christian had to strive to become like Christ. On the black field of this self-portrait Durer brought out two inscriptions in gold: he left the date on the left and his signature monogram on the right, symmetrically to them, wrote: “I, Albrecht Durer, Nuremberg, painted myself with eternal colors.” And next year repeated: “1500”. It was in 1500 that people of that time expected the “end of the world”. In this context, this work of Durer is read as his testament of eternity.

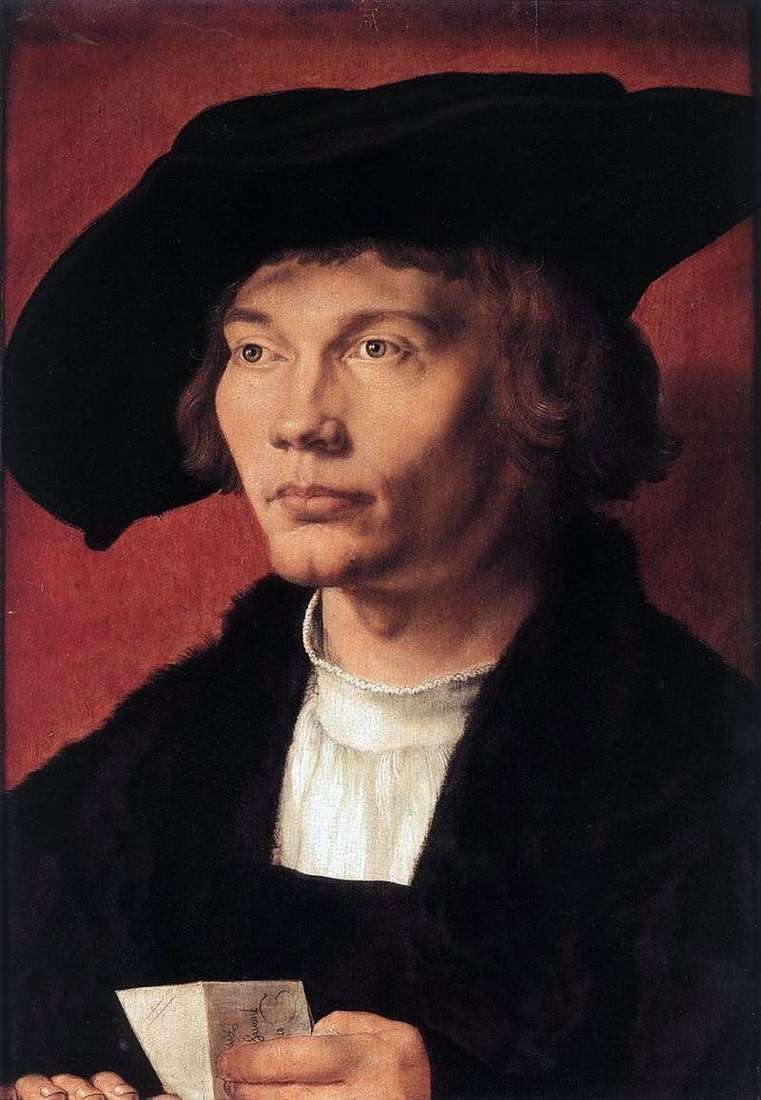

Portrait of the artist’s father by Albrecht Durer

Portrait of the artist’s father by Albrecht Durer Portrait of Jakob Muffel by Albrecht Durer

Portrait of Jakob Muffel by Albrecht Durer Portrait of a father in 70 years by Albrecht Durer

Portrait of a father in 70 years by Albrecht Durer Portrait of Berhart von Riesen by Albrecht Durer

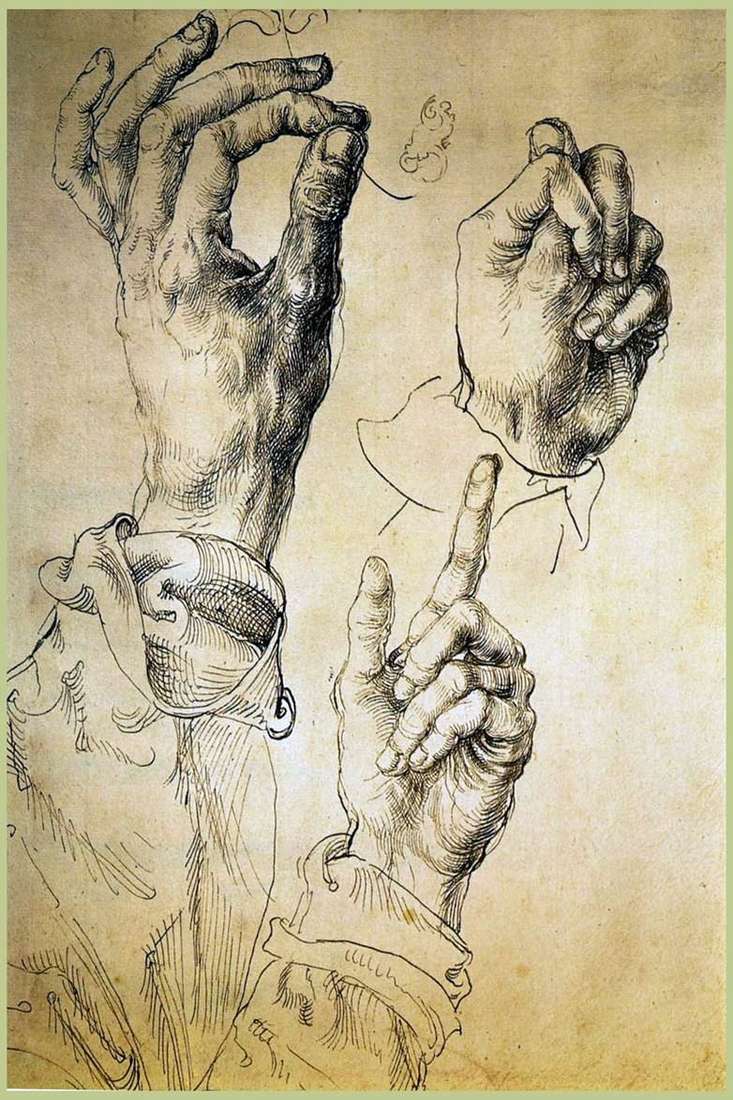

Portrait of Berhart von Riesen by Albrecht Durer Etude “Three Hands” by Albrecht Durer

Etude “Three Hands” by Albrecht Durer Portrait of Barbara Durer by Albrecht Durer

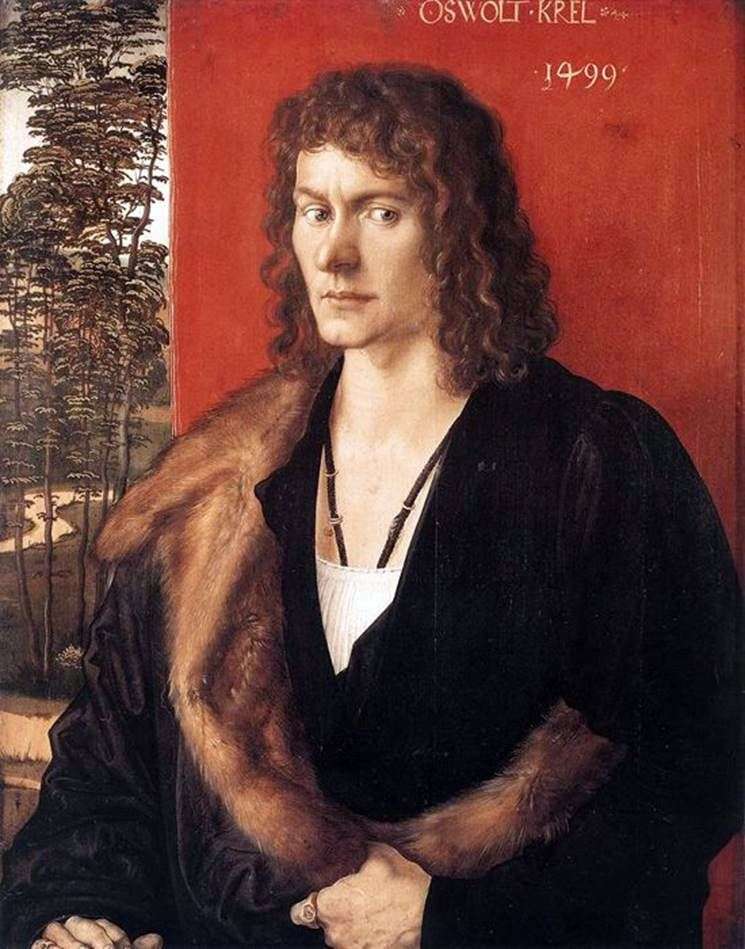

Portrait of Barbara Durer by Albrecht Durer Portrait of Oswald Krell by Albrecht Durer

Portrait of Oswald Krell by Albrecht Durer Portrait of Willibald Pirkheimer by Albrecht Durer

Portrait of Willibald Pirkheimer by Albrecht Durer