Antonis van Dyck, a pupil and younger contemporary of Rubens, is one of the greatest artists of Flanders of the 17th century.

In 1632, Van Dijk, having accepted the invitation of the English King Charles I, moved to London. In the life and work of the painter a new period begins. Promised by the king, who elevated him to a knighthood and married to a noble family member, filled with orders, van Dyke becomes a fashionable portraitist of the English aristocracy. Under a brush of the master there is a gallery of the most prominent representatives of pre-revolutionary England. The artist conveys in the created images a haughty nonentity, and spiritual strength, and beauty of character of heroes.

The portrait of Sir Thomas Chaloner, executed at the very end of the 30s, is an excellent example of custom work. A forty-five-year-old man with a strong-willed, nervous, morbid face framed by a shambles of disheveled hair and a thin lace collar looks at us from the canvas. A black silk cloak was carelessly thrown on his shoulders. With an energetic gesture of his right hand, he points to the hilt of his sword. The precariousness and accuracy of the psychological characteristics of the depicted character were an important conquest of the art of van Dyck.

The artist was able to discern even those character traits that were manifested much later, when Thomas Chaloner witnessed a charge in court over Archbishop Lod, sentenced to treason for high treason, and when he signed the death sentence to Charles I. But, along with strong-willed features, van Dijk marks at the model and a painful flabbiness of a skin, and reddened eyelids, and bags under the eyes, appeared, maybe, a consequence of intemperance. It is known that with the dissolution of the Long Parliament, of which Chaloner was a member, Cromwell called Sir Thomas a drunkard.

“Portrait of Thomas Chaloner” was purchased for the Hermitage in 1779 as part of the famous collection of Walpole. It is interesting to note that during the sale it was issued for the portrait of the father depicted, also called Thomas. Most likely, this was done deliberately, so as not to cause discontent with Catherine II, who, perhaps, would not like to buy a portrait of the “regicide”. Under the erroneous name, the portrait was listed in the Hermitage catalogs until 1893.

Portrait de Sir Thomas Chaloner – Anthony Van Dyck

Portrait de Sir Thomas Chaloner – Anthony Van Dyck Retrato de Sir Thomas Chaloner – Anthony Van Dyck

Retrato de Sir Thomas Chaloner – Anthony Van Dyck Equestrian portrait of Charles I by Anthony Van Dyck

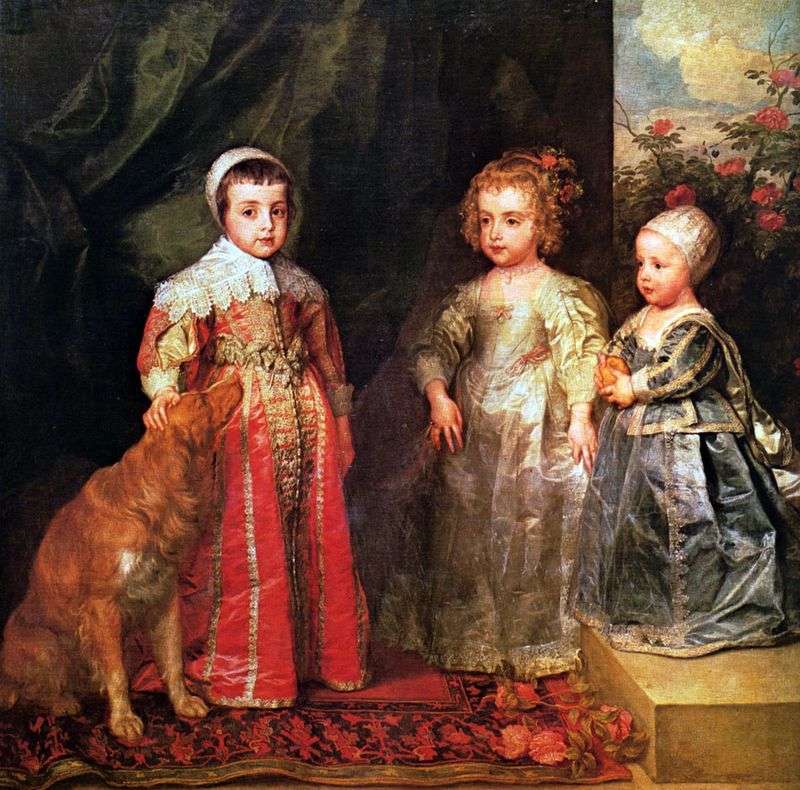

Equestrian portrait of Charles I by Anthony Van Dyck Portrait of three older children of Charles I by Anthony Van Dyck

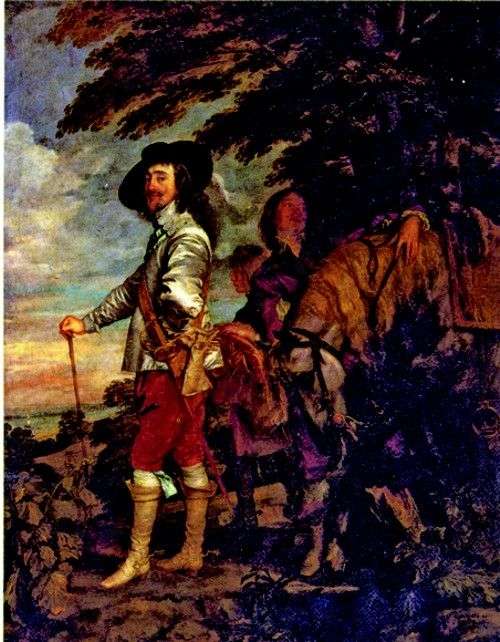

Portrait of three older children of Charles I by Anthony Van Dyck Charles I, King of England, on the hunt by Anthony Van Dyck

Charles I, King of England, on the hunt by Anthony Van Dyck Portrait of James Stewart by Anthony Van Dyck

Portrait of James Stewart by Anthony Van Dyck Portrait of Geronima Brignole-Sale with her daughter Maria Aurelia by Anthony Van Dyck

Portrait of Geronima Brignole-Sale with her daughter Maria Aurelia by Anthony Van Dyck Portrait of Sir Thomas Wharton by Anthony Van Dyck

Portrait of Sir Thomas Wharton by Anthony Van Dyck