The emergence of Pierre Bonnard as an artist coincided with the time when the art was the last battles around impressionism. He witnessed the posthumous triumphs of Cezanne, Van Gogh and Gauguin. Together with his comrades – Denis, Vuillard, Valloton – Bonner joined the group, which was called “Nabi”. Following the precepts of Gauguin, these artists sought a decorative generalization of forms and colors.

In the works of Bonnard the main place is occupied by street sketches, unpretentious pictures of family life, still life and landscape. Bonner develops his own style, which, with pronounced decorativeness, was not so radically innovative as the style of Matisse; a significant role is played by his transfer of space, volume and lighting. In this respect, Bonnard’s work can be regarded as a continuation of the traditions of impressionism. His art undergoes a relatively weak evolution over a long life.

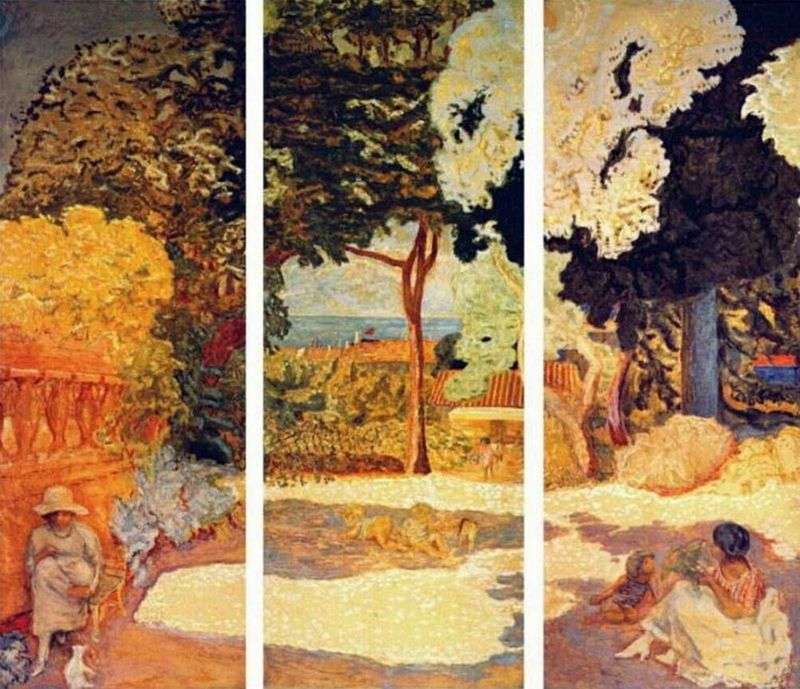

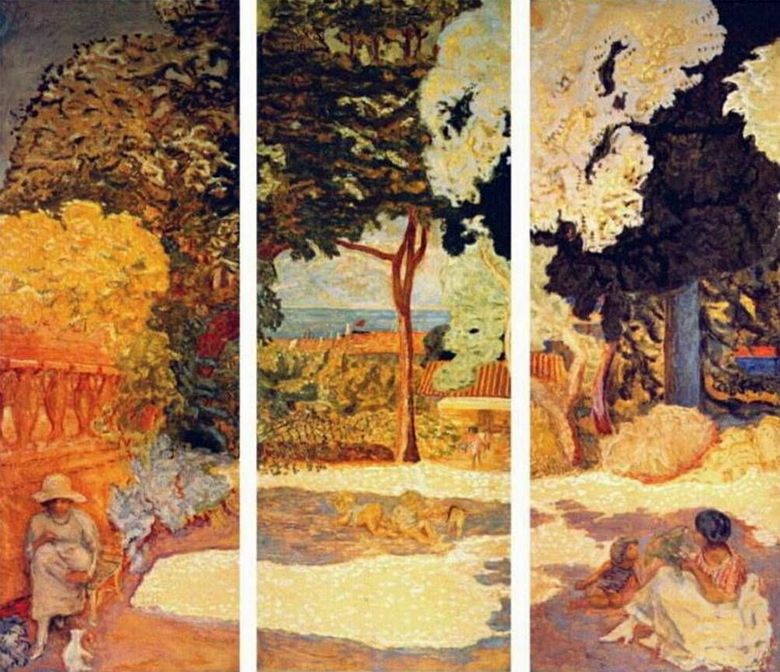

In 1911, the famous Moscow collector IA Morozov ordered Bonnar series of panels to decorate the front staircase of his mansion. For these works, a combination of the tasks of the decorative panel and landscape painting is characteristic. The panel “In Autumn: Collecting Fruits” and “In Early Spring in the Village” are kept in the Museum of Fine Arts named after I. A. Pushkin in Moscow. The Hermitage triptych occupied the end wall of the staircase. According to the artist’s intention, the composition was divided into three parts by white semicolumns, and a sparkling Mediterranean landscape, visible through an antique portico, was revealed before the incoming ones.

… The area in front of the villa is flooded with a hot, dazzling southern sun. On all sides it is surrounded by trees and only in the depth, in the gap between them, can be seen azure sea. Transparent purple shadows almost do not give a cool, and yet the inhabitants of the house rush to hide here in a sultry hour: a woman in a white dress plays with a kitten, another – talking to a parrot, two half-naked kids swarming in the sand. These figures, so characteristic of Bonnard with his attachment to the poetry of everyday life, do not distract the viewer’s attention from the main thing – the luxurious, fantastically abundant southern nature surrounding them.

Most of the composition is occupied by huge bunches of trees; The lush greens of dark, salad, silvery tones define the color of the triptych. Fanciful tree crowns, curved trunks, ragged spots of shadows give rise to the impression of a movement that should have seemed particularly tangible in contrast to strict columns.

The decorative scope is combined in Bonnar with a subtle sense of color: he puts nearby tones close and does not seem monotonous; he uses dozens of shades of green and yellow, lilac and pink, brown and blue, but avoids variegation. For Bonnard, the main thing is not the volume and lines, but the colorful spot, he seeks to emphasize the plane of the picture itself, the alternation of dark and light plans.

The Mediterranean triptych is a thing created in the full power of its enormous pictorial talent.

The painting entered the Hermitage in 1948 from the State Museum of New Western Art in Moscow.

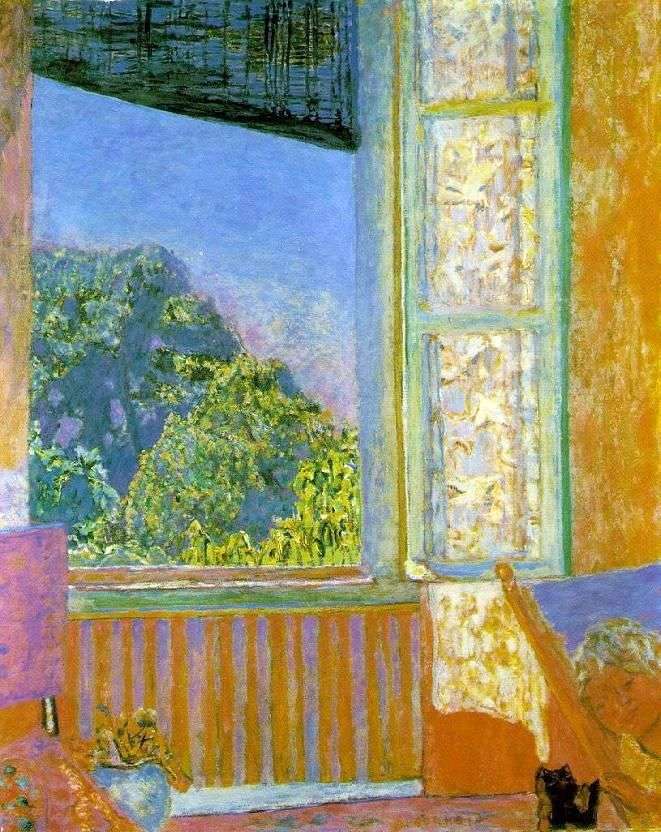

Open Window by Pierre Bonnard

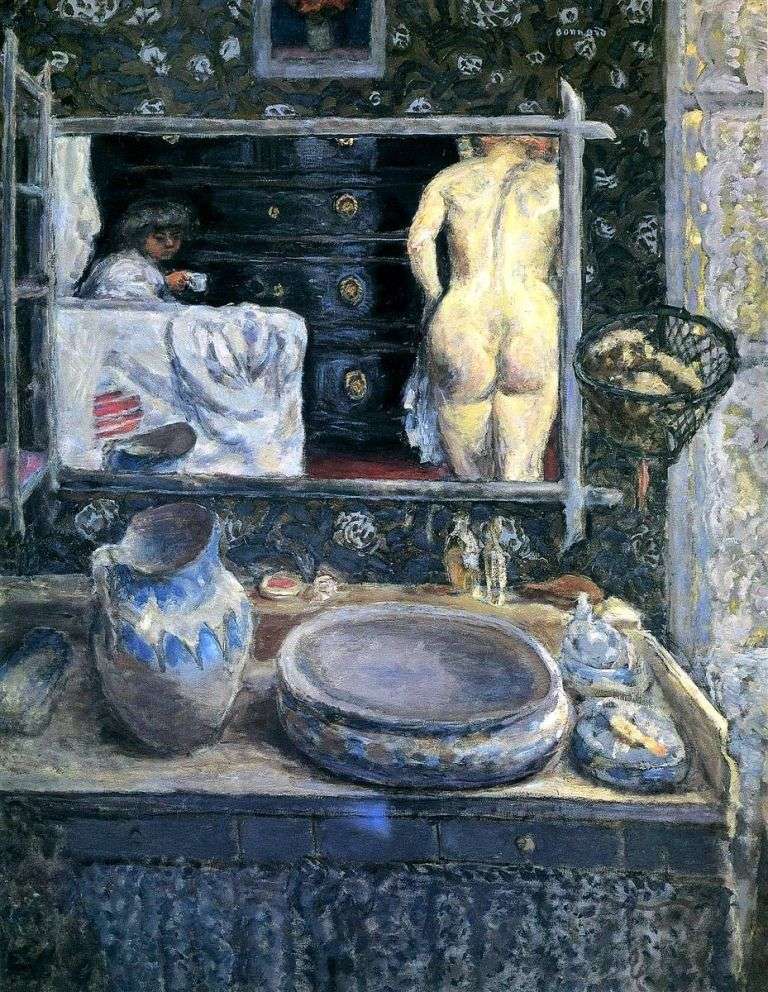

Open Window by Pierre Bonnard Mirror over the sink by Pierre Bonnard

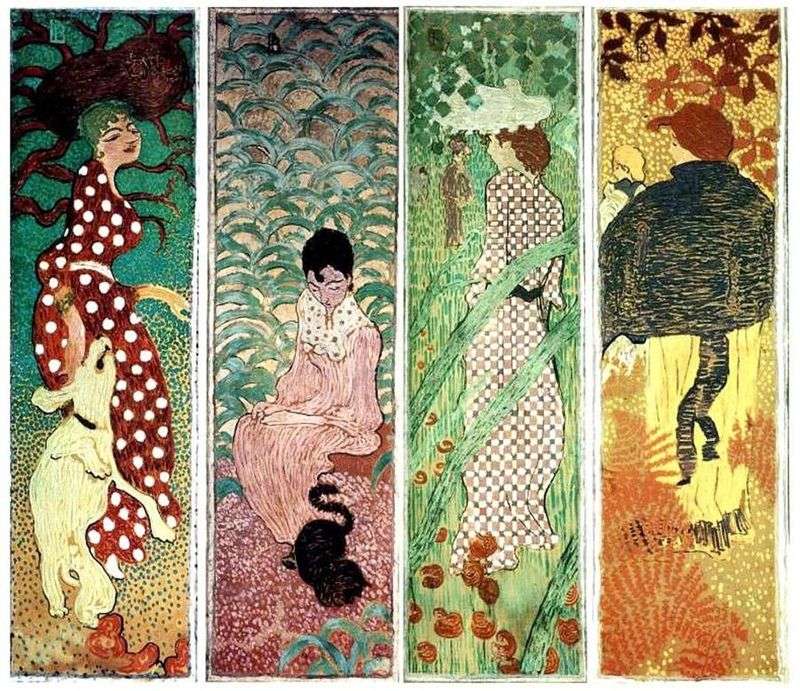

Mirror over the sink by Pierre Bonnard Women in the Garden by Pierre Bonnard

Women in the Garden by Pierre Bonnard Two poodles by Pierre Bonnard

Two poodles by Pierre Bonnard Workshop with mimosa by Pierre Bonnard

Workshop with mimosa by Pierre Bonnard Lodge by Pierre Bonnard

Lodge by Pierre Bonnard Par la Méditerranée – Pierre Bonnard

Par la Méditerranée – Pierre Bonnard Nanny on a walk by Pierre Bonnard

Nanny on a walk by Pierre Bonnard