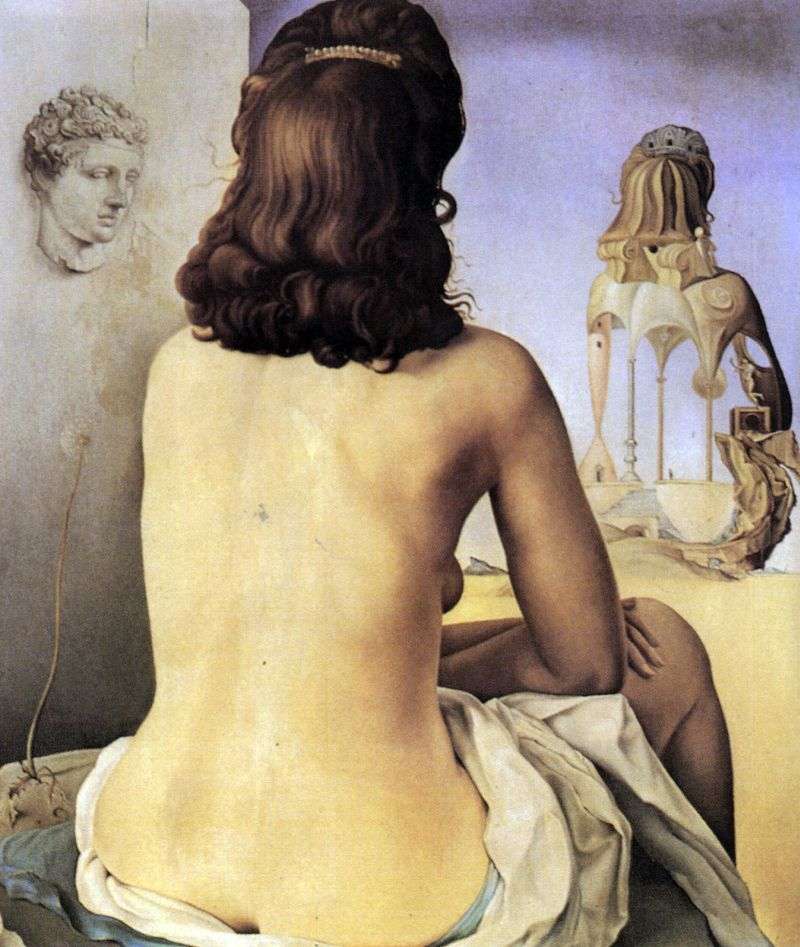

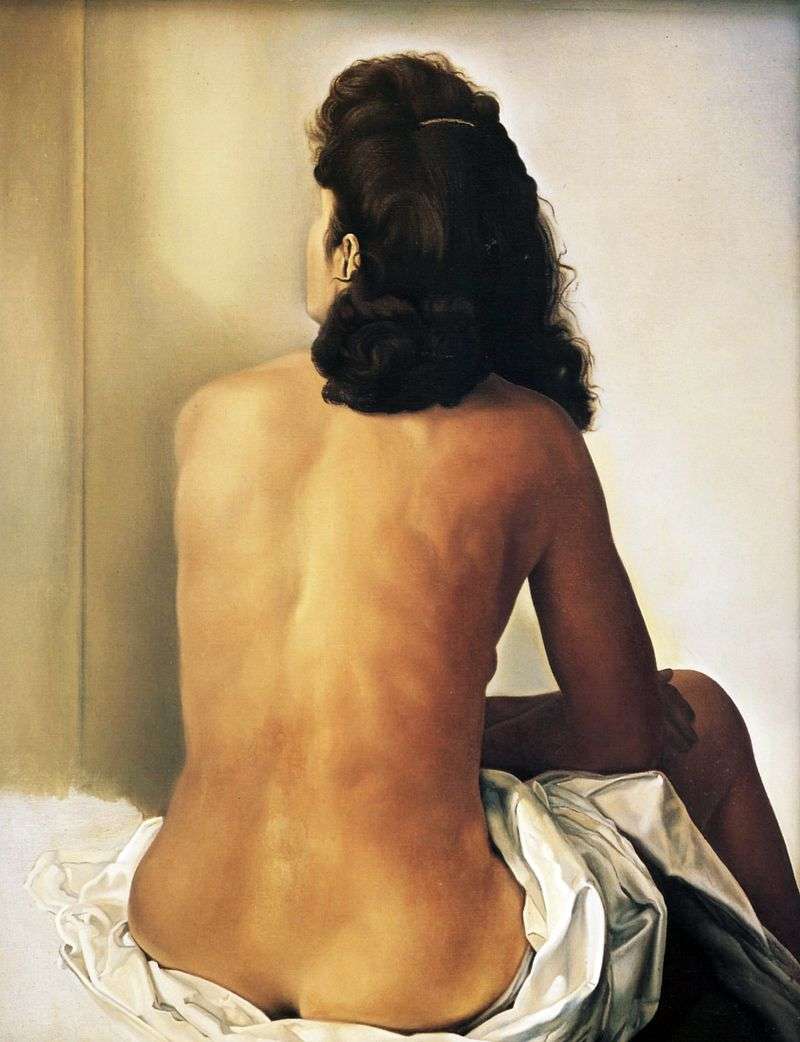

The full name of the painting is “My wife, naked, looks at her own body, which has become a ladder, three vertebrae of the column, sky and architecture.” The model – the wife and the artist’s muse – is depicted twice. Like a flesh-clad image of a beautiful woman with a perfect body – and as his geometrically idealized projection onto the plane of the heavenly background.

The first plan is the sitting naked Gala, which is back to the viewer. To her left is a wall with a plaster mask. Perhaps this mask is a tribute to the favorite techniques and subjects of classical painting, which Dali often addressed during that period of his work. Next to the woman grows a dandelion: fluffy, not yet flown. If the masked wall looks like the personification of the eternal and unshakable, then the dandelion here, most likely, is an allegory of fleetingness.

Cracks are visible on the wall. A little shaggy hair models seem like a continuation of these cracks. A woman looks forward to the projection of her own body in the desert space. On the projection, the hairpin in her hair was transformed into a comb or semblance of a crown. Upon closer examination, the “crown” is the entrance leading to the inside of the head.

The figure-projection, contours ideally repeating a prototype, has lost corporeality and properties of a flesh. It is turned into an openwork gazebo with columns and a tent roof through which the heavens shine through. The arbor became the setting for the sky. Rather, for its fragment, limited by the architectural form. The sky in the gleam of the gazebo is also part of the projection of Gal, it is appropriated by it and melted in it.

One of the bright childhood impressions of Dali, in his recollections, was the empty chitinous shell of a dead insect and the sky visible through the holes in this shell. The echo of this memory over and over again forced the artist, in search of absolute purity, to look at the heavens through the flesh.

In that part of the celestial vault, which is outlined and taken prisoner by the contour of the trunk-gazebo, you can see two circles. At first the eye snatches the circle and identifies it as the disc of the setting sun. But a little to the left and further looms one more, less. Then comes the understanding that the first disc is, most likely, the projection of the right breast of the prototype woman. Inside the gazebo is a sculpture on the pedestal: vaguely discernable, but outlines reminiscent of the classical antique statue of Hermes.

In general, the composition of the picture makes one think about the dual nature of the author’s music. She is both a material earthly woman and her bizarre reflection in the eyes of a genius madman.

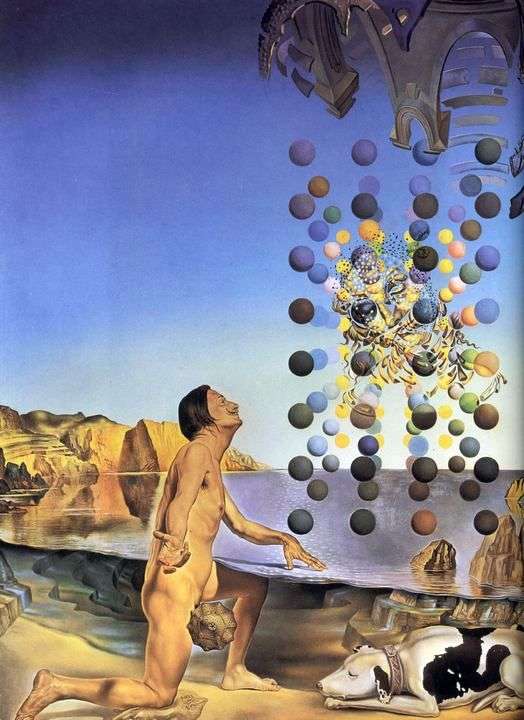

Naked Dali in front of five regular bodies by Salvador Dali

Naked Dali in front of five regular bodies by Salvador Dali Anxious sign by Salvador Dali

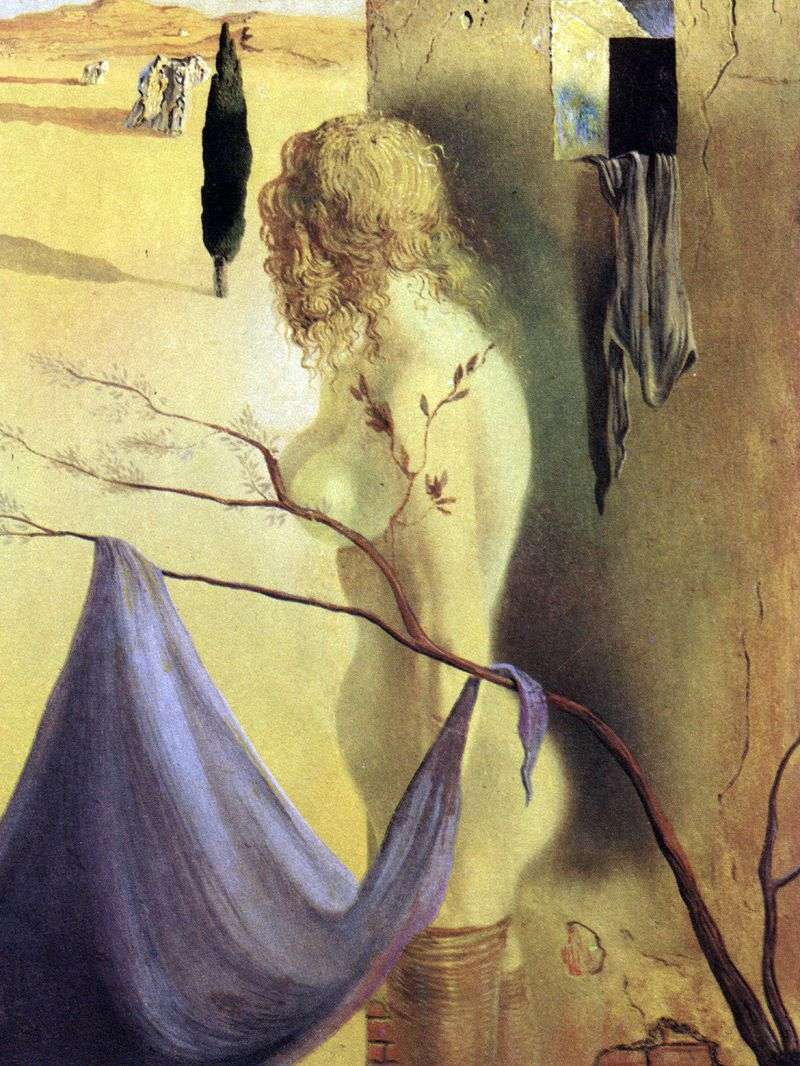

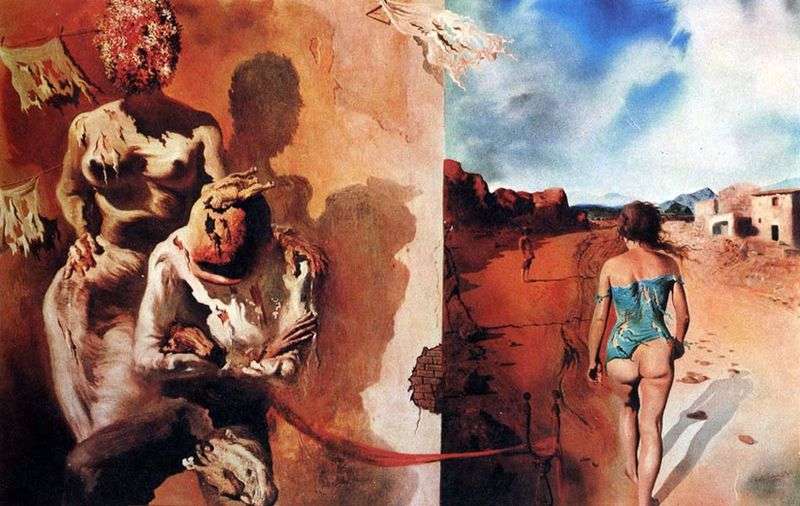

Anxious sign by Salvador Dali Honey is sweeter than blood by Salvador Dali

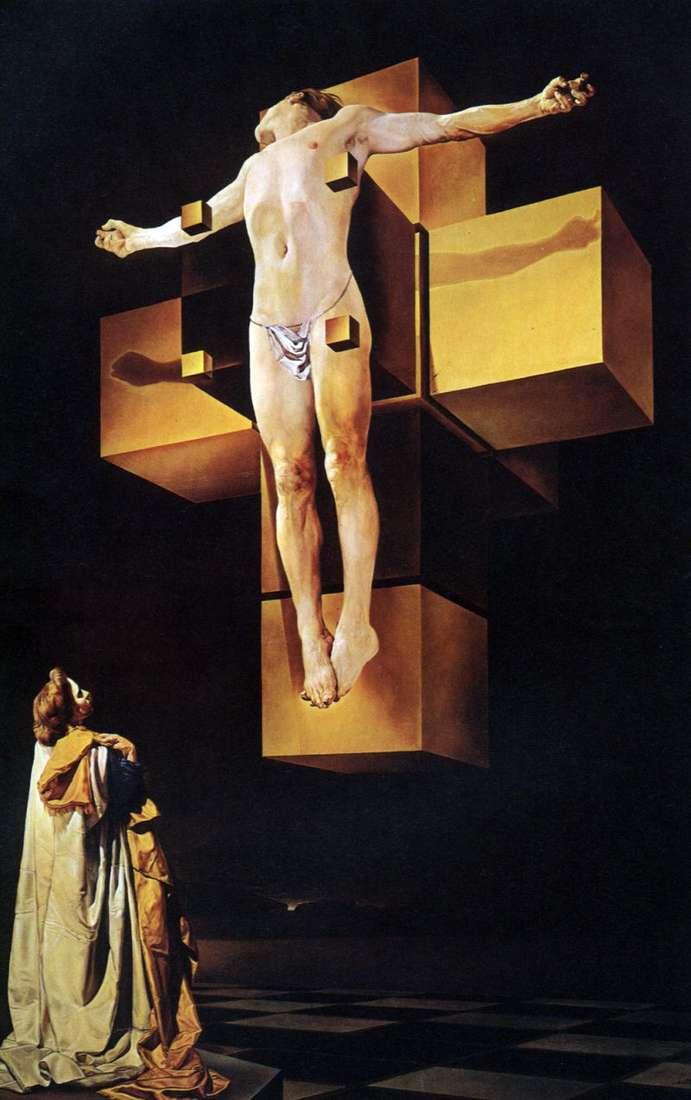

Honey is sweeter than blood by Salvador Dali The Crucifixion by Salvador Dali

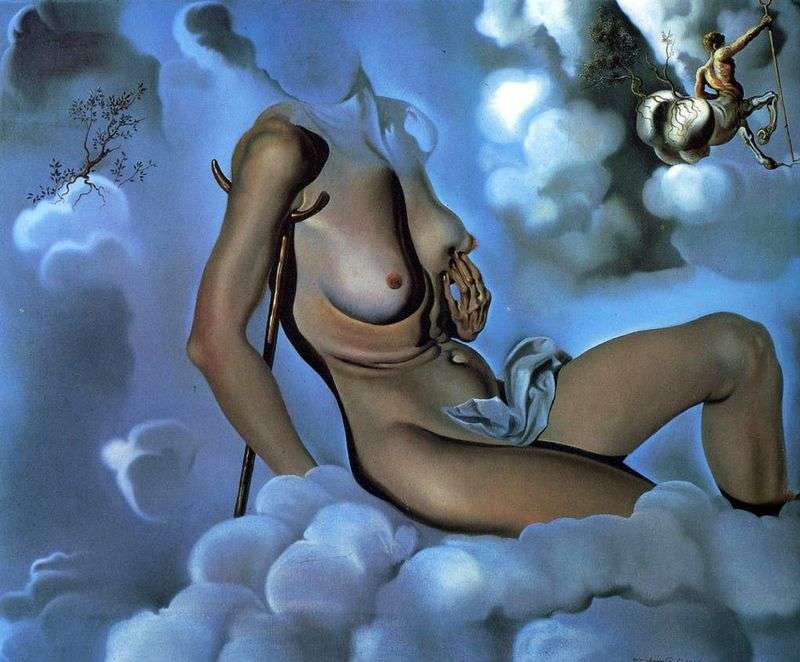

The Crucifixion by Salvador Dali A sleeping woman in the background of a landscape by Salvador Dali

A sleeping woman in the background of a landscape by Salvador Dali Sleep laying a hand on the male back by Salvador Dali

Sleep laying a hand on the male back by Salvador Dali Nude Gala sitting with her back by Salvador Dali

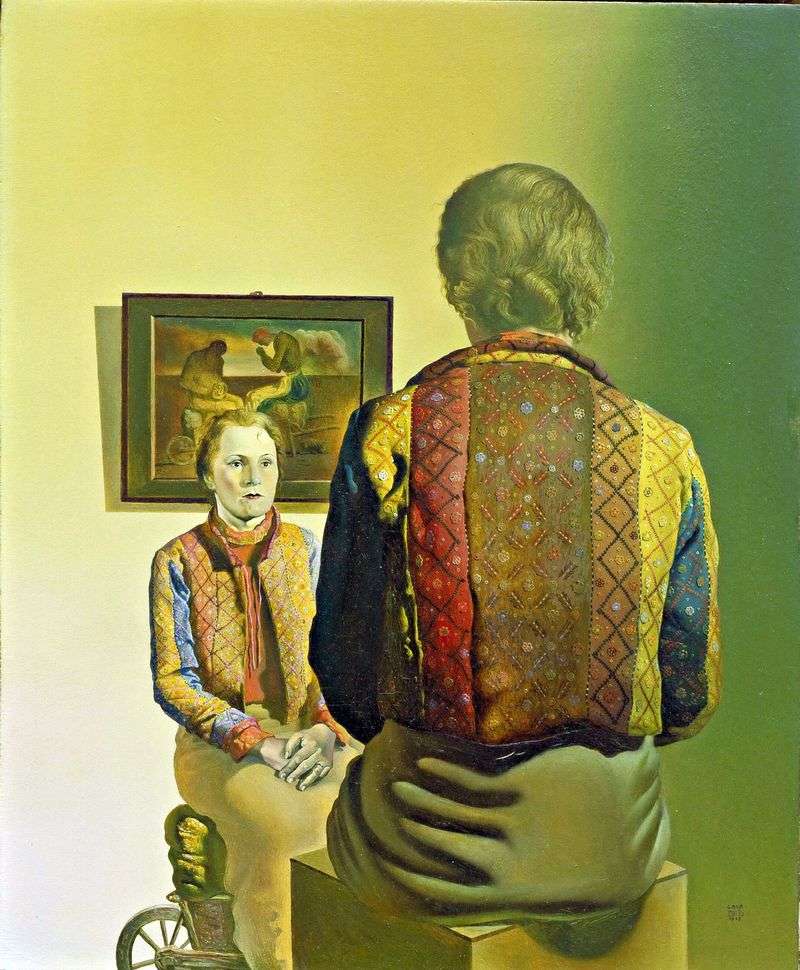

Nude Gala sitting with her back by Salvador Dali Portrait of Gala by Salvador Dali

Portrait of Gala by Salvador Dali