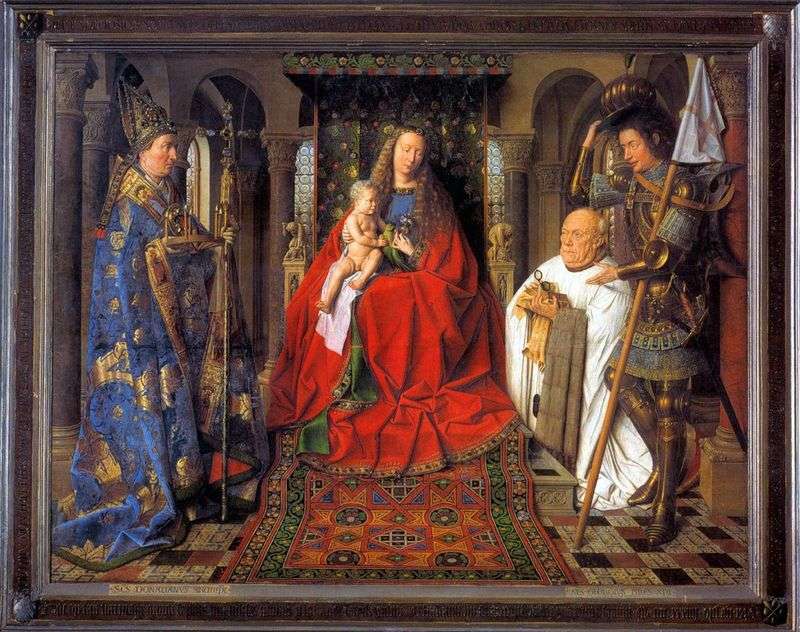

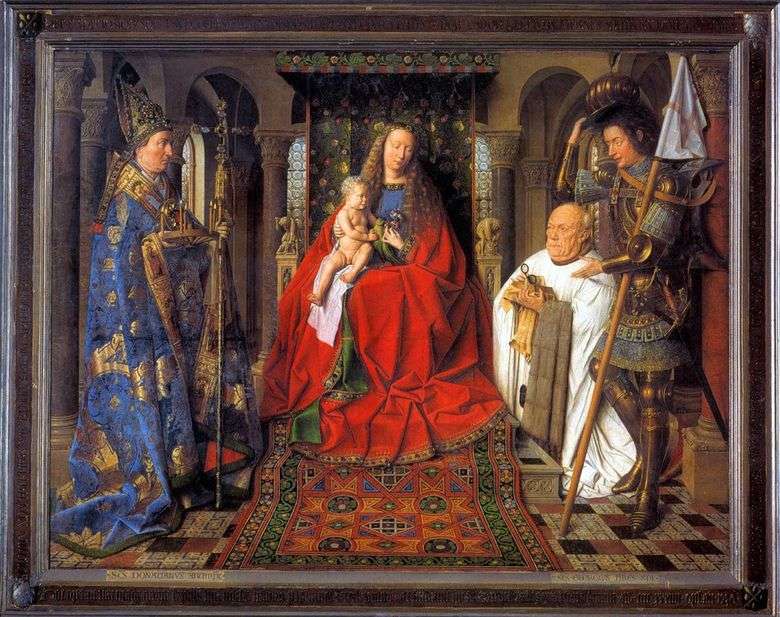

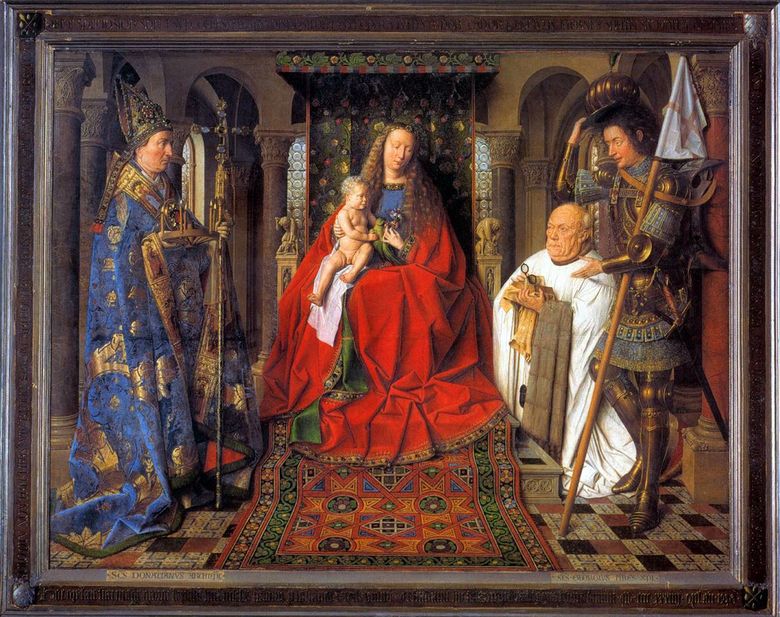

This picture is the largest work of van Eyck after the Ghent altar. Again, the sense of reality in the transfer of space, light and objects, as well as the effect of the presence of figures captures the spirit of the viewer. This became possible thanks to special technical methods, ahead of the new “academic” rules of the Italian Paintings of the time, with which van Eyck was for sure familiar. A compact and symmetrical group of figures is surrounded by a colonnade in the form of a semicircular apse. The bases of the front columns are not combined with the perspective of the floor. This discrepancy is intentional and is a consequence of the van Eyck spatial scheme, which is based on local points of convergence. This method allowed the artist to create the impression of a real large space that is next to the viewer.

The system consists in dividing the picture plan into several overlapping zones, each of which has its own point of departure. Perhaps this is not as empirical and intuitive as is commonly believed, but it represents a competitive alternative to the Italian system with a single point of convergence, which is only suitable for space at a less obtuse angle. The semicircular arch, which does not exceed the figures by its height, emphasizes the religious function of the room. However, the depicted architectural elements do not play the role of a frame as much as emphasize the giant proportions of figures.

The pretentious architecture in the Romanesque style is surprisingly similar to the non-preserved choirs of the Church of St. Donatsian, judging by their portrayals of the 18th century. The location of the whole group on the choir, and the altar serves as a throne for the Virgin Mary, hints at the sacrament of the Eucharist. That is why the canon is dressed in surplice. On the pilaster capitals in the dark gallery depicts Old Testament episodes, including small statuettes of Cain with Abel and Samson with a lion on the pillars of the throne. Jesus and Mary are the new Adam and Eve, who are represented in niches under sculptures. Heroic plots next to St. George symbolize the triumphant struggle against Evil. Next to Saint Donatsian is the sacrament of the Eucharist, which, thus, becomes a sacred ceremony.

The column behind St. George is markedly different in color from the other columns. Thus van Eyck sought to symbolically point out the sacred struggle and blood of Christ. It’s hard to think of a better example of the use of symbolism in a realistic image. The frame is depicted in the form of a carved stone window on which the text on the left, top and right is cut out. The inscription below is encrusted with gold. Embossment to the letters is given by the same light source. When you look at it from this angle, the frozen character of the scene inside the frame appears: it is an imitation of a giant color sculpture made of stone and metal. It is interesting that the characters in the picture form separate blocks of colors: blue, red, white and gold. Do these colors coincide with the colors of the coat of arms of the city of Bruges? Gold, red and blue are also present on the canon of the canon and his family and on the decorative elements of the chapel. During the life of the artist, this picture was as popular as his “Ghent Altar”. This is because she was in the church, and not in a private collection, like many other works of the artist.

Madonna canon van der Palet by Jan van Eyck

Madonna canon van der Palet by Jan van Eyck Stigmatization of St. Francis by Jan van Eyck

Stigmatization of St. Francis by Jan van Eyck Madonna Canon Canon van der Pale – Jan van Eyck

Madonna Canon Canon van der Pale – Jan van Eyck Madonna in the church by Jan van Eyck

Madonna in the church by Jan van Eyck Lucca Madonna by Jan van Eyck

Lucca Madonna by Jan van Eyck Madonna Canon Van der Pale – Jan van Eyck

Madonna Canon Van der Pale – Jan van Eyck Madonna Canon Van der Pale – Jan van Eyck

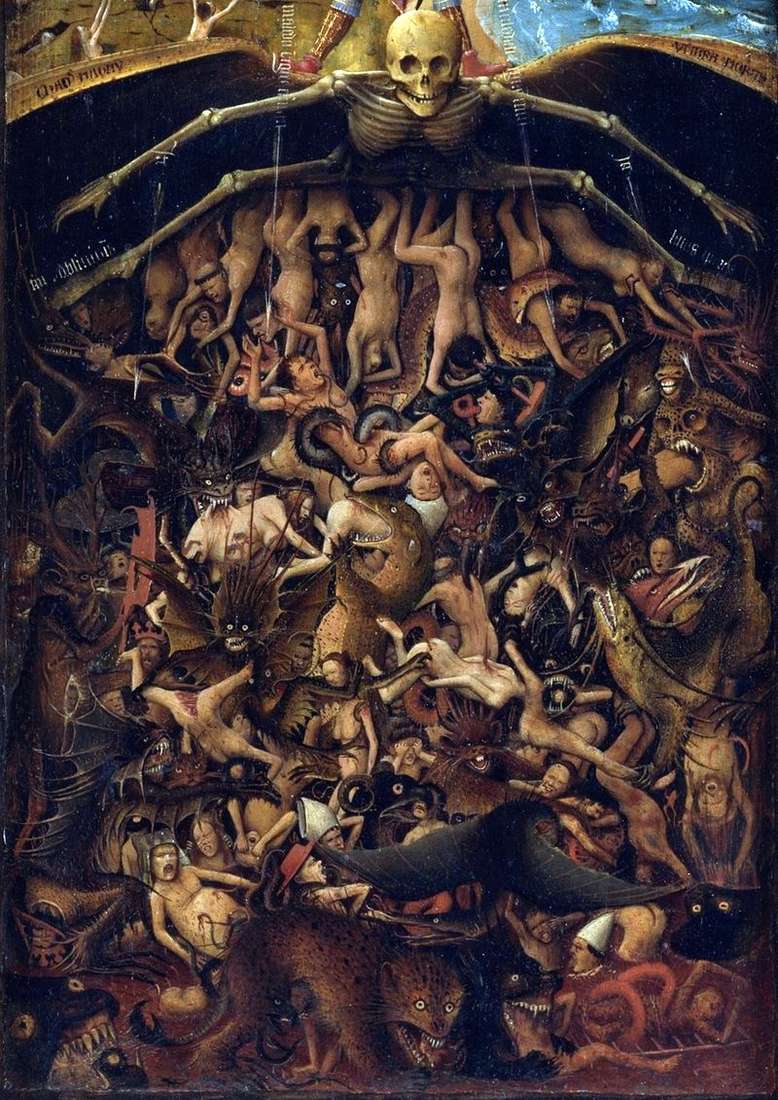

Madonna Canon Van der Pale – Jan van Eyck The Last Judgment by Jan van Eyck

The Last Judgment by Jan van Eyck