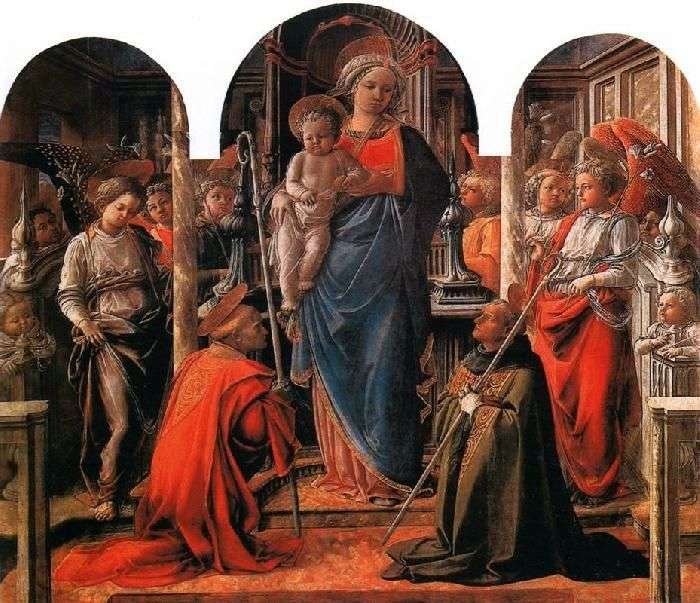

In the mature years of creativity, Lippi wrote polyptychs for the altar of the Barbadori Chapel in the Church of the Holy Spirit in Florence. In this work, he managed to combine the sublime, almost sculptural forms of Masaccio with the true vitality of figures and objects.

For the altar, they chose the form of a polyptych, because it exactly corresponded to the tasks of a single action and a single space. The columns in the Lippi picture do not coincide a bit with dividing it into three parts, which creates the illusion of expanding space. Angels, unconstrainedly positioned around the stately Madonna and the large, but seemingly weightless, Infant Christ, whom she only slightly supports near her thigh, look in different directions.

The Mother of God moves freely, rising from the throne towards two kneeling and concentrated saints. The demonstration of underlined piety, characteristic of earlier altars, is clearly not the main task of the image. This holy gathering is already close to turning into a holy discourse, which later became the norm of the art of the Renaissance.

Cool tones restrain the overall color of the picture. But on this background brighter, warm notes are distinctly sounding. Red color spots together with golden light are reflected in the folds of clothes, in shades of faces and hands. They bring freshness to the space of the image, creating a sense of fullness and richness of the painting. Madonna Filippo Lippi from the altar Barbadori came to the Louvre in 1814 as part of a collection of paintings of the early Renaissance, taken out by Baron Vivan-Denon from Tuscany.

Vierge à l’enfant entourée d’anges, avec les saints Frediano et Augustin – Filippo Lippi

Vierge à l’enfant entourée d’anges, avec les saints Frediano et Augustin – Filippo Lippi Madonna y el niño, rodeados de ángeles, con los santos Frediano y Agustín – Filippo Lippi

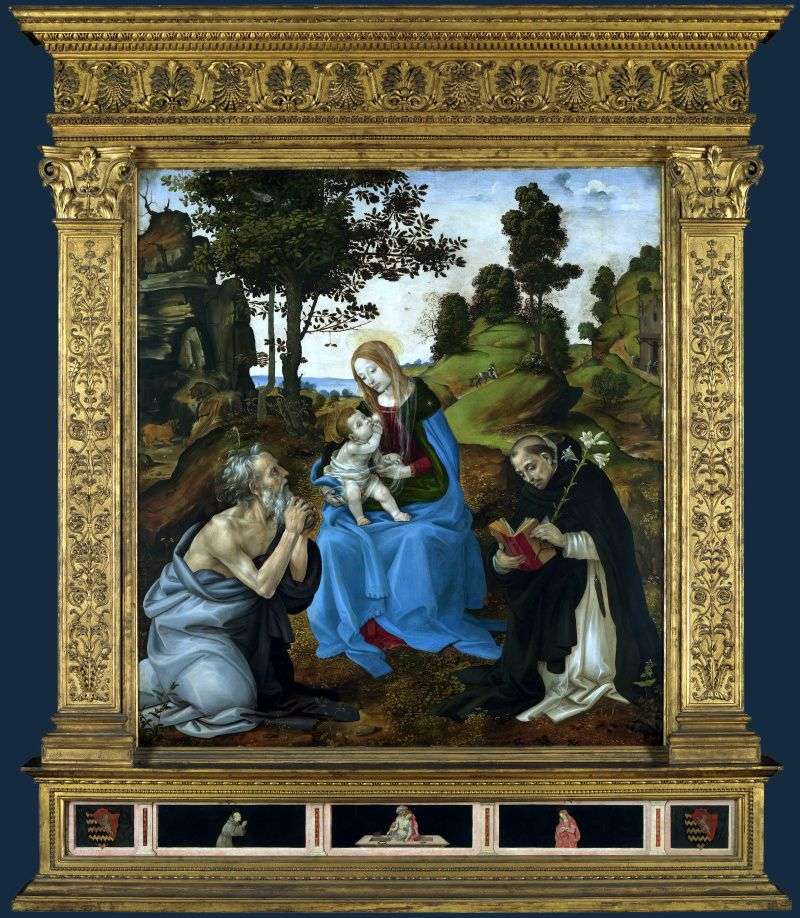

Madonna y el niño, rodeados de ángeles, con los santos Frediano y Agustín – Filippo Lippi Madonna and Child with Saints Jerome and Dominic by Filippino Lippi

Madonna and Child with Saints Jerome and Dominic by Filippino Lippi Maria and the baby on the throne, surrounded by the saints Juvenal, Sabina, Augustine, Jerome and six angels by Giovanni Boccati

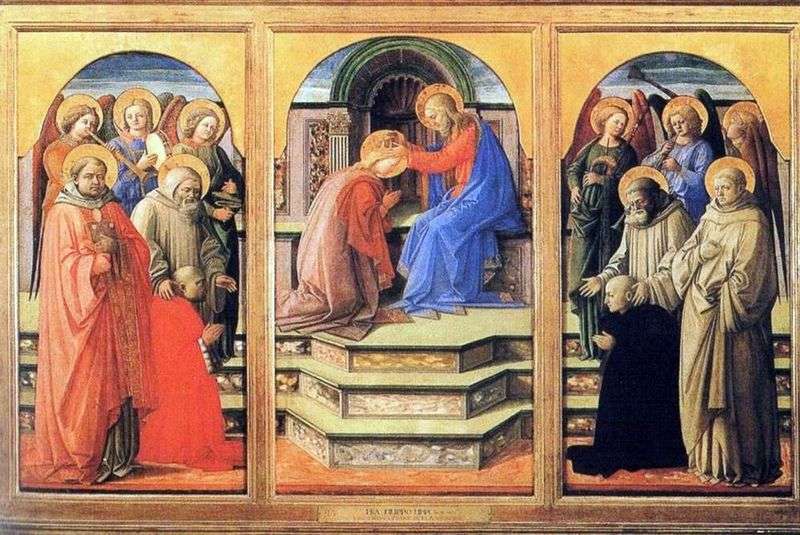

Maria and the baby on the throne, surrounded by the saints Juvenal, Sabina, Augustine, Jerome and six angels by Giovanni Boccati The Crowning of Mary by Fra Filippo Lippi

The Crowning of Mary by Fra Filippo Lippi Virgin and Child on a throne surrounded by angels by Chenny Di Pepo

Virgin and Child on a throne surrounded by angels by Chenny Di Pepo Madonna and Child, surrounded by angels, of sv. Roses and St. Catherine by Pietro Perugino

Madonna and Child, surrounded by angels, of sv. Roses and St. Catherine by Pietro Perugino Madonna with Child and Saints by Giovanni Bellini

Madonna with Child and Saints by Giovanni Bellini