The plot of the film “Freedom on the Barricades”, exhibited in the Salon in 1831, is addressed to the events of the bourgeois revolution of 1830. The artist created a kind of allegory of the alliance between the bourgeoisie, represented in the picture by a young man in a cylinder, and the people that surrounds him. True, by the time the picture was created, the union of the people with the bourgeoisie had already disintegrated, and it had been hidden from the viewer for many years.

The painting was bought by Louis-Philippe, who financed the revolution, but the classic pyramidal composition of this painting emphasizes his romantic revolutionary symbolism, and vigorous blue and red strokes make the plot emotionally dynamic. A clear silhouette against the background of a bright sky rises the young woman embodying Freedom in a Phrygian cap; her breast is bare. High above her head she holds the French national flag.

The look of the heroine of the canvas is directed at a man in a cylinder with a rifle embodying the bourgeoisie; to her right is a boy, Gavroche, waving pistols, a national hero of the streets of Paris. The painting was presented to the Louvre by Carlos Beystegi in 1942; in the Louvre collection was included in 1953. “I chose a modern plot, a scene on the barricades… If I did not fight for the freedom of the fatherland, then at least I should celebrate this freedom,” Delacroix told his brother, referring to the picture “Freedom leading the people.” The call in it for the struggle against tyranny was heard and enthusiastically received by contemporaries. On the corpses of the fallen revolutionaries barefoot, with bare chest, Freedom, calling for the rebels. In her raised hand she holds a tricolor Republican flag, and its colors are red,

In his masterpiece, Delacroix combined, seemed incompatible – protocol realism of the reportage with a lofty cloth of poetic allegory. A small episode of street fighting, he gave a timeless, epic sound. The central character of the canvas is Freedom, combining the stately posture of Aphrodite of Milo with the features Liberty bestowed on Auguste Barbier: “This is a strong woman with a mighty chest, with a hoarse voice, with fire in her eyes, quick, with a wide step.” Encouraged by the success of the revolution of 1830, Delacroix began work on the picture on September 20 to glorify the Revolution. In March 1831 he received a reward for her, and in April he exhibited a painting in the Salon.

The painting with its furious force repelled the bourgeois visitors, who also reproached the artist for showing only “mob” in this heroic act. At the salon, in 1831 the Ministry of the Interior of France buys “Freedom” for the Luxembourg Museum. After 2 years, “Freedom,” whose story was considered too politicized, was removed from the museum and returned to the author. The king bought the painting, but, frightened by her character, dangerous during the period of the bourgeoisie’s kingdom, ordered to hide, roll up, then return to the author. In 1848, the painting requires the Louvre. In 1852 – the Second Empire. The picture is again considered subversive and sent to the store. In the last months of the Second Empire, Freedom was again viewed as a great symbol, and engravings from this composition served the cause of republican propaganda.

After 3 years, it is extracted from there and demonstrated at the World Exhibition. At this time, Delacroix rewrites it again. Perhaps it makes the darker the bright red tone of the hood to soften its revolutionary look. In 1863, Delacroix dies at home. And after 11 years, “Freedom” again exhibited in the Louvre. Delacroix himself did not take part in the “three glorious days,” watching what was happening from the windows of his workshop, but after the fall of the monarchy, the Bourbons decided to perpetuate the image of the Revolution.

Liberty Leading the People by Eugene Delacroix

Liberty Leading the People by Eugene Delacroix Liberté guidant le peuple (Liberté sur les barricades) – Eugene Delacroix

Liberté guidant le peuple (Liberté sur les barricades) – Eugene Delacroix Moroccan family by Eugene Delacroix

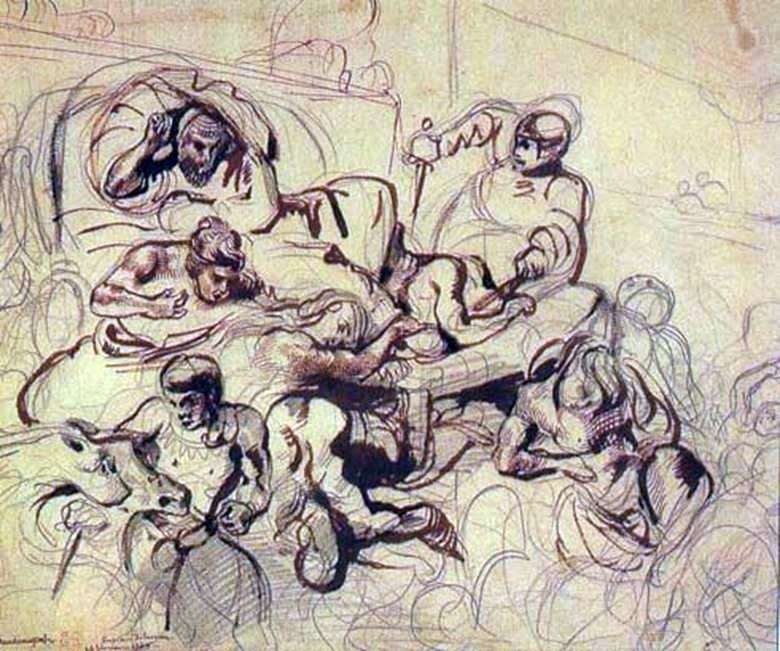

Moroccan family by Eugene Delacroix Sketch for the painting Death of Sardanapal by Eugene Delacroix

Sketch for the painting Death of Sardanapal by Eugene Delacroix The death of Sardanapal by Eugene Delacroix

The death of Sardanapal by Eugene Delacroix Portrait of Baron Schweiter by Eugene Delacroix

Portrait of Baron Schweiter by Eugene Delacroix Lion devouring a rabbit by Eugene Delacroix

Lion devouring a rabbit by Eugene Delacroix A tiger playing with his mother by Eugene Delacroix

A tiger playing with his mother by Eugene Delacroix