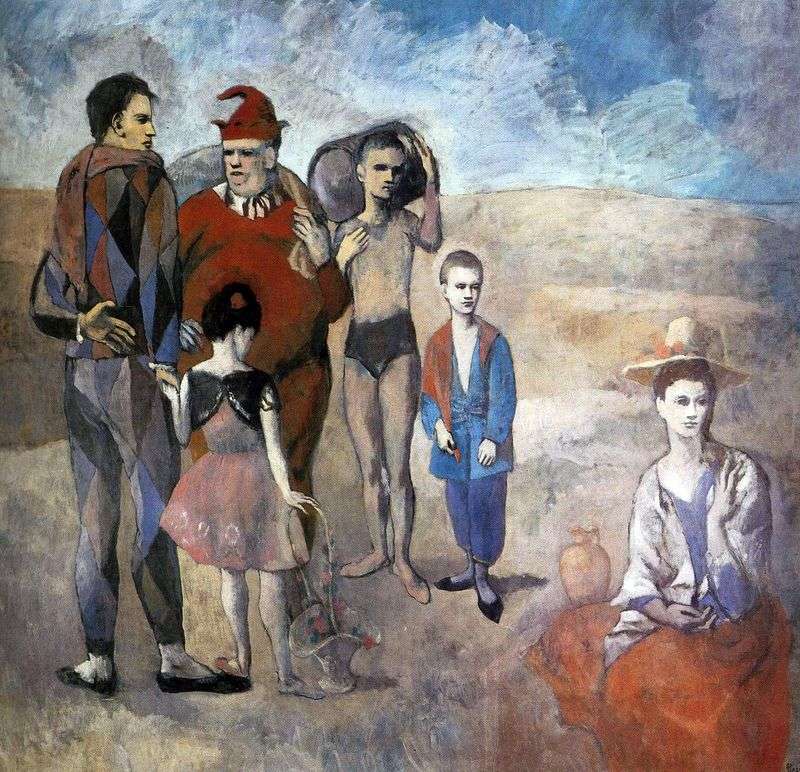

The “pink” period retains a generally gloomy feeling, letting in, however, the notes of life in pink-golden-scarlet tones. A hint of movement, lightness appears in these pictures. In the “pink” period, the “Family of an acrobat with a monkey” is created. Strange, but the artist who had previously rejected simple human joys began to write people united by a simple human community.

A circus troupe, cut off from the outside world, is an extraordinary affinity within itself. The figure of a circus harlequin, gently and reverently bending over a child in the arms of a woman, and a monkey sitting at the feet of the artists evoke pity and a barely noticeable feeling of something unusually strong and significant that bound their destinies together.

During participation in the Resistance, the Popular Front, Picasso seems to draw inspiration from a life-giving source. His works, unusually fruitful, for the first time begin to really exist for people. These are landscapes, still lifes, portraits, monumental canvases, decorative ensembles, lithographs, sculptures, illustrations for books. Hope, light, ironic indulgence replace the alienated sarcasticity that raged before in Picasso. The election of the artist to the World Peace Council in 1950 marked the recognition by humanity of the great artist’s contribution to the struggle for peace.

The rapid history of one of the most famous paintings of Picasso began in the spring of 1937, when the Nazi bombardment destroyed the Basque city of Guernica. Spanish poet and prominent public figure Rafael Alberti later recalled: “Picasso never went to Gurney – v ke, but the news of the destruction of the city struck him like a blow from a bull’s horn.” Indeed, this canvas measuring 3.5 m in height and about 8 m in width Picasso wrote in less than a month.

Picasso took for the basis of the plot and composition of the picture not the development of a real event, but the associative links of the images born by his shocked consciousness. The images of the picture are transmitted in a simplified, generalizing strokes – only that which cannot be dispensed with is drawn, everything else is rejected. In the faces of the mother and the man, turned to the viewer, only the mouth wide open in a scream, visible openings of the nostrils, moving somewhere above the forehead of the eye, are left. Any individuality, any details would be superfluous here, could split up and thereby narrow the general idea.

The tragic feeling of death and destruction of Pablo Picasso ventured to convey the agony of the artistic form itself, which breaks objects into hundreds of small fragments. Next to the mother, holding in her arms a dead child with its head thrown back, stands a bull with an expression of grim indifference on its face. Everything around is dying, and only this bull rises above the fallen people, keeping them fixed on their eyes.

This contrast of indifference and suffering in the first sketches of “Guernica” was almost the main support of the whole picture, but Picasso did not stop there, and in the right side of the canvas, next to a man who threw his hands up, two human faces appeared but with features undistorted, beautiful and determined.

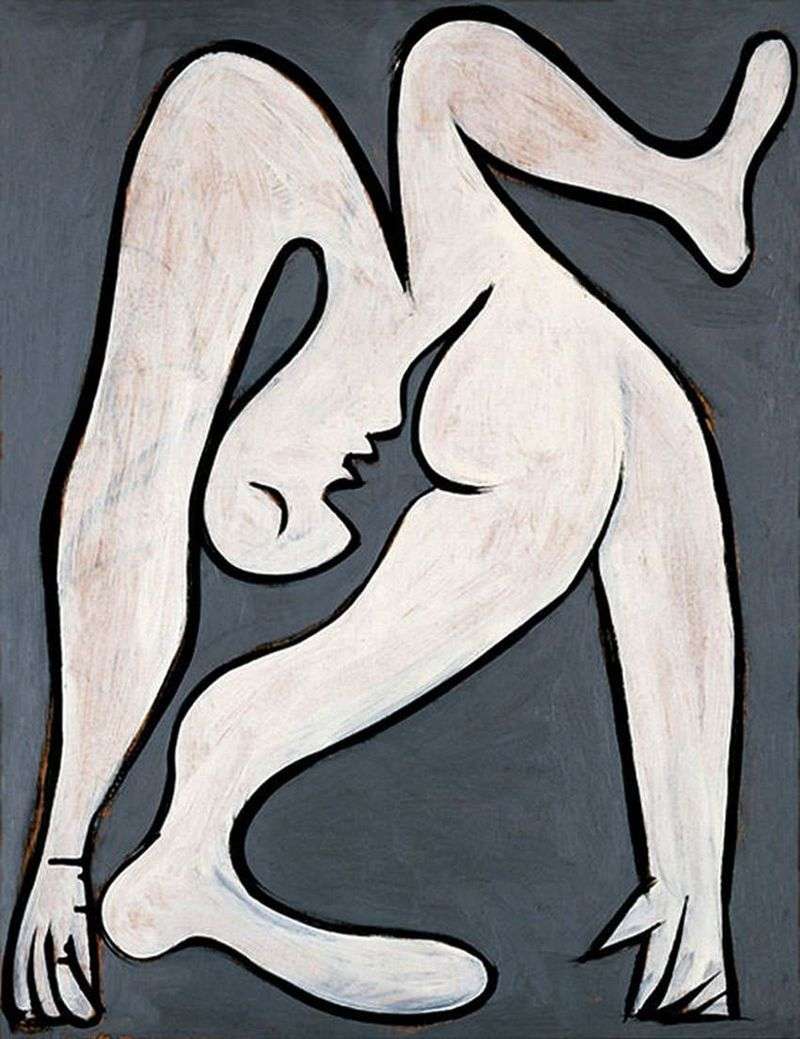

Acrobat by Pablo Picasso

Acrobat by Pablo Picasso Family of Comedians by Pablo Picasso

Family of Comedians by Pablo Picasso Boy with a dog by Pablo Picasso

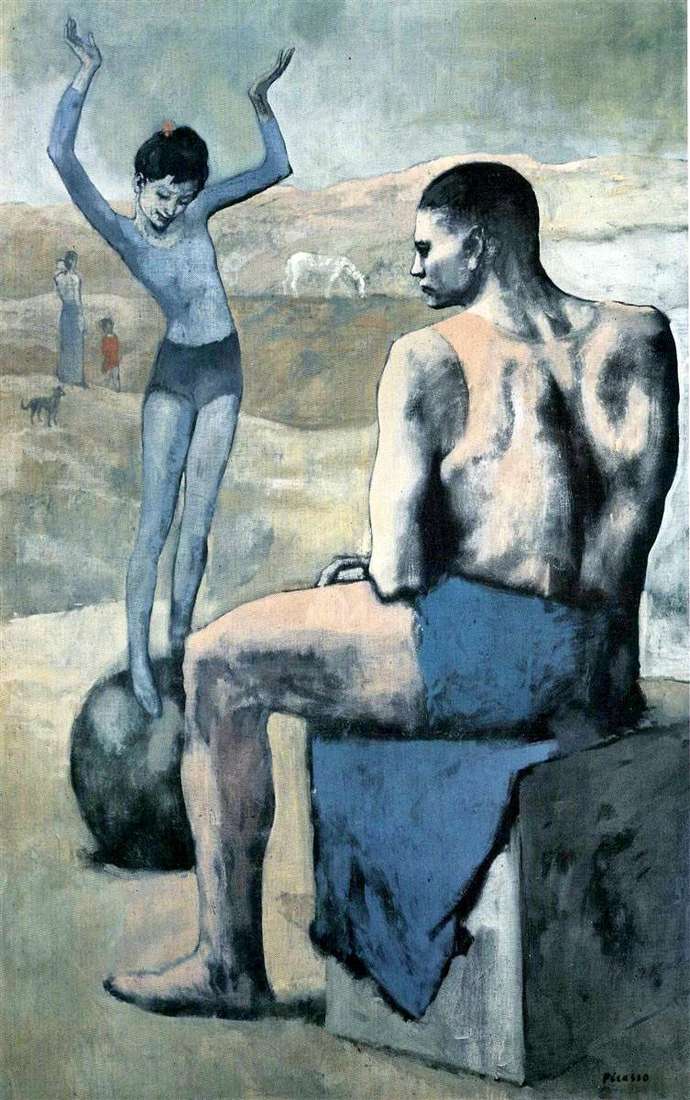

Boy with a dog by Pablo Picasso The girl on the ball by Pablo Picasso

The girl on the ball by Pablo Picasso The girl on the ball by Pablo Picasso

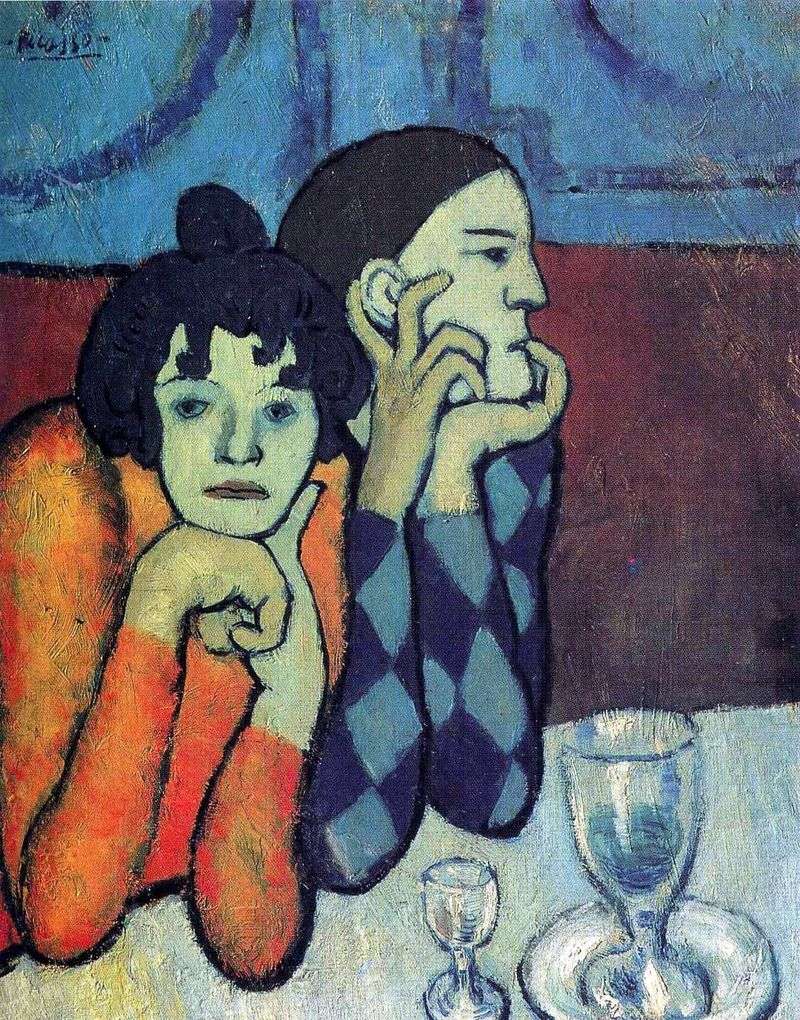

The girl on the ball by Pablo Picasso Harlequin and his girlfriend by Pablo Picasso

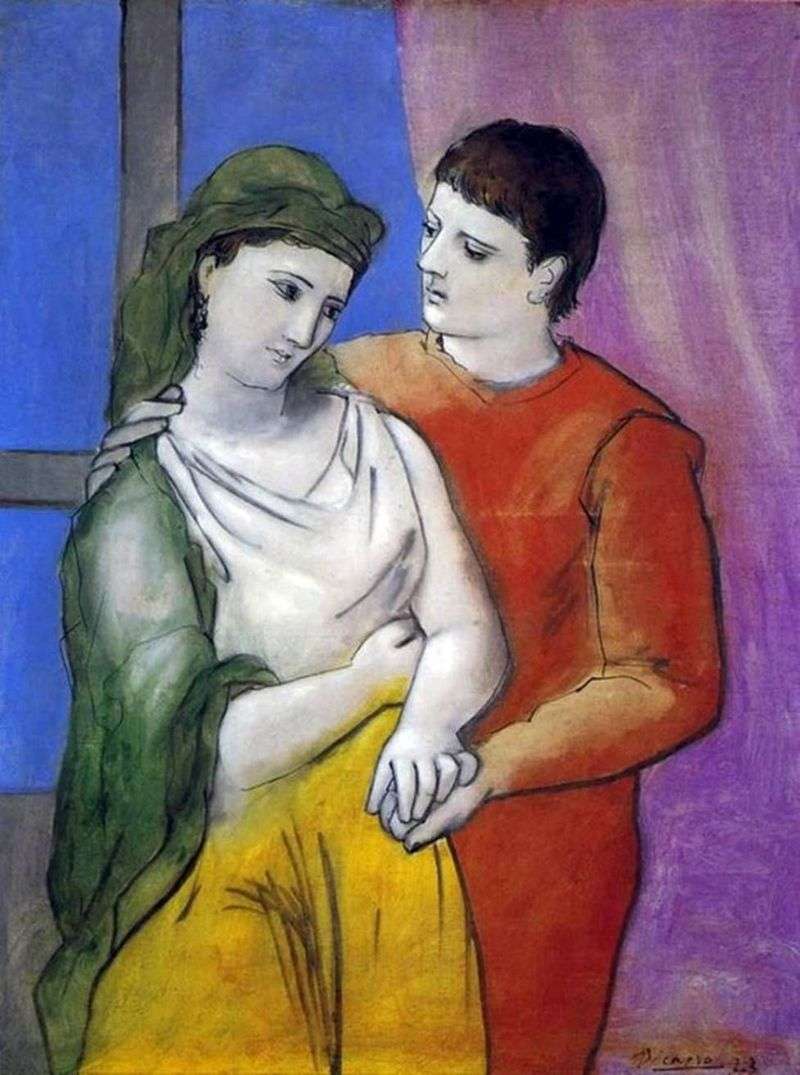

Harlequin and his girlfriend by Pablo Picasso Lovers by Pablo Picasso

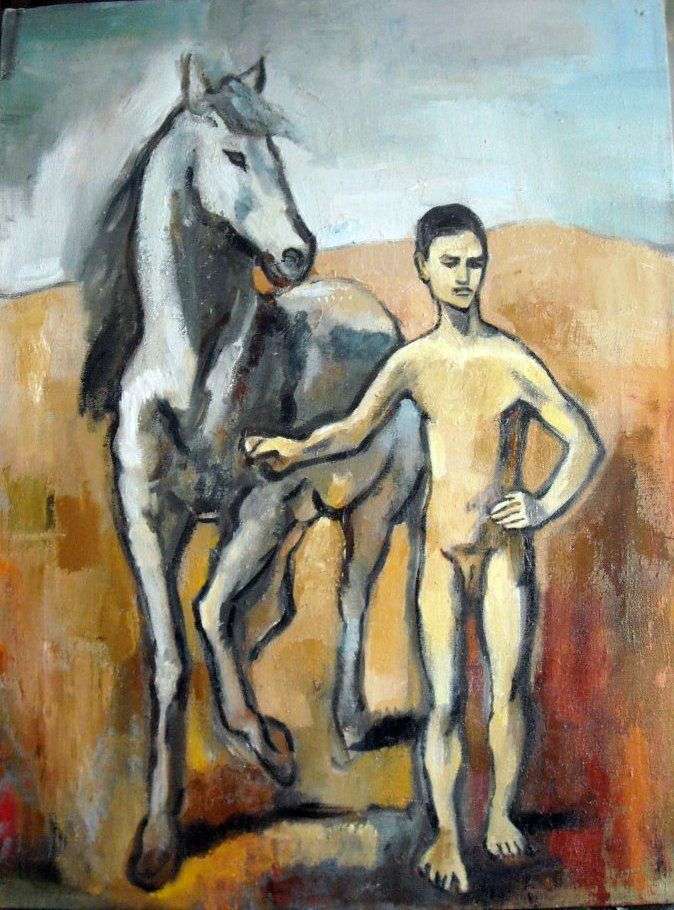

Lovers by Pablo Picasso The boy is the lead horse by Pablo Picasso

The boy is the lead horse by Pablo Picasso