Dirk worked on the product for about four years, which is rather strange: according to the terms of the contract, he did not have the right to take another order before the end of the Sacrament. The painting was commissioned by the Brotherhood of Holy Sacraments for St. Peter’s Church in Louvain. It was intended for the altar of one of their chapels – the second radial chapel in the covered arcade on the north side near the chapel of St. Erasmus. The room was granted to the brotherhood in the year of its foundation.

Right opposite the altar was located in the early 1450’s cancer for the storage of guests. The altar was to become “a valuable historical work conveying the plot of the holy mysteries.” The main theme was the Last Supper and four scenes “or figures from the Old Testament” on the doors. In the closed state, additional images were to be present on each leaf, but they were not preserved. During the restoration, the central part was transferred to the canvas, as was done with the Martyrdom of Saint Erasmus.

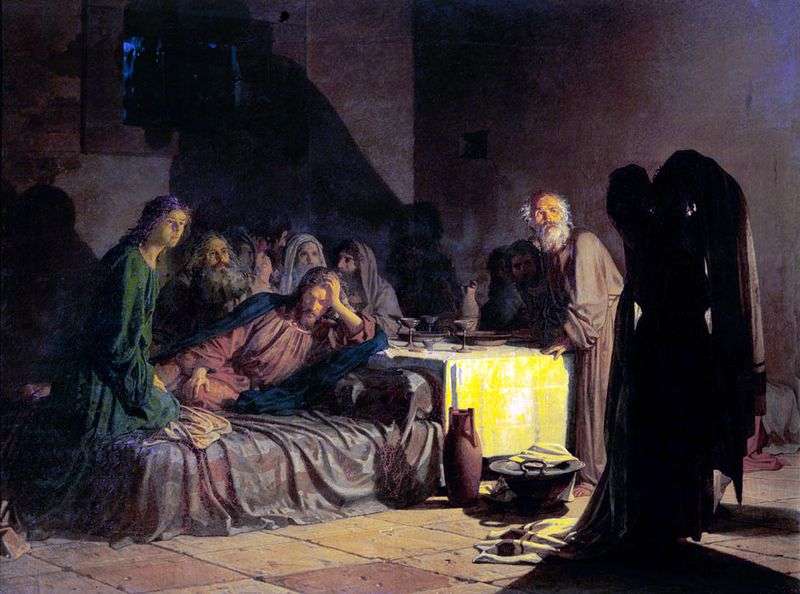

The artist was assisted in the work of two theologians: University professor Jan Warenaker and Gilles Bayluvel; their advice in many ways determined the manner of depicting the Last Supper. According to the Synoptic Gospels, the evening before the arrest of Jesus fell on the Jewish Passover, when in honor of the feast they killed and ate the sacrificial lamb. Jesus gathered his disciples at the table to bless the bread and wine, which he called flesh and blood. The historical moment of the establishment of the sacrament of the Eucharist is depicted here in the form of a liturgy of transfiguration adopted by the Church later.

The new in the work is the depiction of Christ in the role of a contemporary priest who conducts a ceremony of consecration of bread and wine. Since the action takes place in the environment of the numerous attributes of the Jewish Passover, the continued existence of the rite throughout the history of mankind is highlighted graphically: this is expressed in strong contrast to the more traditional images of the breaking of bread, the society of apostles, or the betrayal of Judah.

Dinner is held in a spacious room, which is more like a monastic refectory than a dining room in a big house. High Gothic windows on the left overlook the market square, where the construction of the Louvain City Hall was started. For her, Bates later wrote Scenes of Justice, similar to those that van der Weyden performed for the Brussels Town Hall. Transparent only the upper parts of the windows, as evidenced by their gray color. The lower parts can be covered with shutters because of cold weather or patterned wooden bars. To the right is an open annex with a sideboard for storing dishes. The rear side adjoins another room, apparently the bedroom, where there is a bed with a red veil.

The ornamental arch leading to the corridor of the doorway depicts the predecessor of Christ Moses. The corridor with a washbasin and a water container located in its niche leads to the garden with a geometric layout. The light falling on the left fills the room, sliding along the yellowish-white walls and reflecting off the dazzling white table cloth. Penciled with geometric patterns of beige, brown and blue tiles, the floor reminds of the cold purity of the monastic cell. The shadows from the benches under the table are intertwined with the bare feet of the apostles. Unlike the darkness described in the Gospel, a bright day reigns in the picture. The bronze chandelier is high, and the hearth is closed by a wooden summer screen.

Christ sits in the middle of a large room, raising his head; his blessing hands are at the very center of the composition. He looks directly at the viewer, half-open mouth utters the words: “This is my flesh.” His face is the canonical image of Christ for the fifteenth century. This idealized portrait of Jesus corresponds to the medieval notions of his appearance on the basis of a detailed description in Lentulus’s apocryphal letter. Such elements as parting, curly locks of hair and a beard divided in two are quite recognizable. A gesture of blessing such as that of the Savior of the world, which Jesus is; through the mystical transformation of the guest, he becomes simultaneously a servant of the Mass and a sacrifice.

Some of the apostles at the table are easy to recognize. To the right of Jesus is Peter, to the left – John, next to him Jacob. Since he is a relative of Jesus, there is some similarity. Most of the apostles are depicted in a state of astonishment and delight at the establishment of a new rite. Those who sit closest to Jesus express their joy at the sacrifice of the guest. This rite was more important than the sacrament, and only the priest had the right to perform it. The Eucharist – the spiritual perception of the sacrificed body – filled the hearts of people with piety, which was to lead them to eternal bliss. Jacob looks at Judas with pity; the latter is held aloof, it can be recognized by a typical Semitic profile, which medieval artists have always exaggerated. Judas looks at the tin plate,

This is an allegory of the death of Christ, which will come as a result of betrayal, as well as a reminder of Jesus’ words about the traitor among the apostles. Although everyone tasted the lamb, the tablecloth and long common napkins are still clean, because the table should symbolize the altar. In a moment Christ as a priest will pour wine from the crystal vessel into the chalice and offer to drink it as his own blood. In general, for Bates’ works, an inconspicuous transition from everyday reality to sacral symbolism is typical: the roots of this reception should be sought in a new religious perception embodied in the sermons of “new worship.” Near the focal point on the left, two figures observe what is happening. It’s probably portraits. Two Bauts’ sons, also artists Dirk and Albert, immediately come to mind. Before them – two forgotten tin plates with the remains of food.

In this scene, Dirk Bouts uses a perspective with a single point of descent, depicting the exact diagonal lines on the tiled floor. The point of descent is located high – in the middle of the lintel above the hearth. This allows you to look at the table from above; but it seems that the room itself is at a certain height. It is not known whether such a prospect is a consequence of the decision of the two advisers of the artist, although in favor of this assumption is said atypical for this context almost square form of the table. It occurs in the Life of Jesus Christ Ludolphus Cartesian. He devoted several chapters to the ritual of the Eucharist. Perhaps Ludolfus was partly inspired by the book Meditationes Vitae Christi, recorded in the late 13th century by the Franciscan monk Johannes de Colibus. There is described a square table; the same table can be seen in the church of St. John Lateran, where it is preserved as a relic. Three apostles must sit on each side; Bauts slightly changed their arrangement so that Jesus could be clearly seen.

The professors defined the themes of the two flaps, choosing the scenes from the Old Testament that preceded the Eucharist.

To view the personalities or events from the Old Testament as predictors of a new era that began with the birth of Christ was a favorite occupation of the theologians of the time. These aspects are often illustrated with engravings for visual presentation by the uneducated public. Of these books, the poorest Bible used the most popular, in which illustrations from the New Testament were located above the corresponding events from the Old. In the illustrated edition of another religious text of the above Ludolphus for the Last Supper, her prototypes follow: Manna collection. Easter, Meeting Abraham with Melchizedek. It was these stories that were chosen for the altar and supplemented with the fourth, rarely seen image – the Angel, which brings food to the prophet Elijah in the desert. In the contract, these four scenes are listed in heraldic, rather than chronological order: not from left to right, but vice versa. This suggests that the description of the scenes should have been based on a carefully thought out sketch, which was lost.

In the upper part of the left wing, the high priest Melchizedek offers bread and wine to Abraham; they stand outside the gate of Salem – the residence of Melchizedek.

It can be argued that pointing to the scene on the left are two figures in black robes – these are the same professors. Below is a scene of collecting the manna from heaven, sent down by the god Yahweh to the Jewish people during his journey to the Promised Land. In the upper part of the right wing there is a scene of eating the Easter lamb and matzah before the exodus from Egypt. In the lower part, the emaciated Elijah is depicted asleep. He had to flee to the wilderness after the killing of the priests of Baal. The angel gives him power from the bread he has brought; In the background, Elijah is again on the road. The general name of all these scenes is matzah. The Melchizedek is the forerunner of Christ; lamb symbolizes the future sacrifice, which will open the gates to the heavenly promised land.

In general, this work is the pinnacle of the master’s work, for paintings which are characterized by religious concentration, restraint and attractive contemplation.

Sacrement de la Sainte Communion – Dirk Bouts

Sacrement de la Sainte Communion – Dirk Bouts Madonna and Child on the Throne with Saints Peter and Paul by Dirk Bouts

Madonna and Child on the Throne with Saints Peter and Paul by Dirk Bouts Madonna feeding the Infant by Dirk Bouts

Madonna feeding the Infant by Dirk Bouts Wonder of a Cowl by Paolo Uccello

Wonder of a Cowl by Paolo Uccello The Last Supper by Nikolay Ge

The Last Supper by Nikolay Ge Sacramento de la Sagrada Comunión – Dirk Bouts

Sacramento de la Sagrada Comunión – Dirk Bouts The Temptation of Christ by Sandro Botticelli

The Temptation of Christ by Sandro Botticelli Peasant family by Louis Lenin

Peasant family by Louis Lenin