Jacopo da Ponte, nicknamed for the city, in which, with the exception of his young years, when he studied in Venice, spent his whole life, was nevertheless popular in Serenissima. And so much so that it was to him that Veronese sent his son as a pupil. This dramatic composition enjoyed its success, the emergence of which coincided with the era of the counter-reformation – the spiritual search for new meanings of religious experience, resilience in resisting temptations, “free knowledge,” personal responsibility.

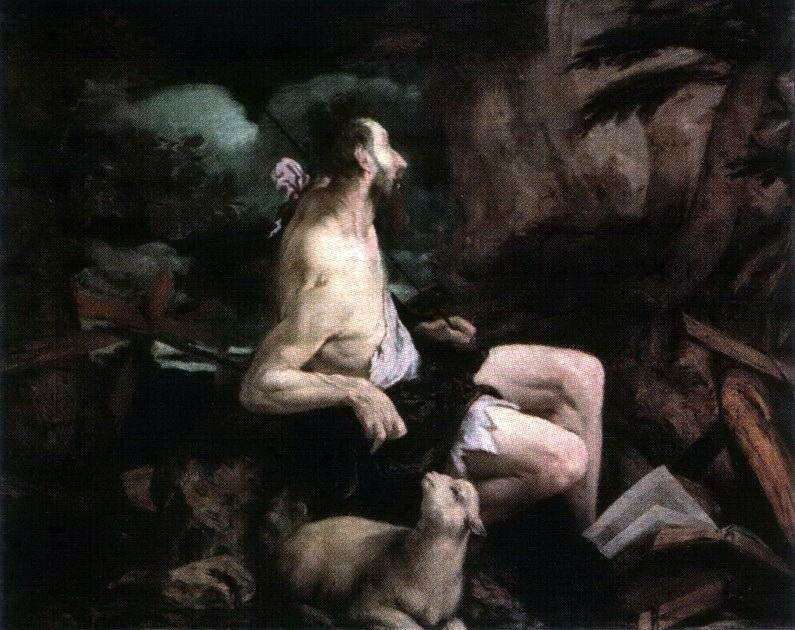

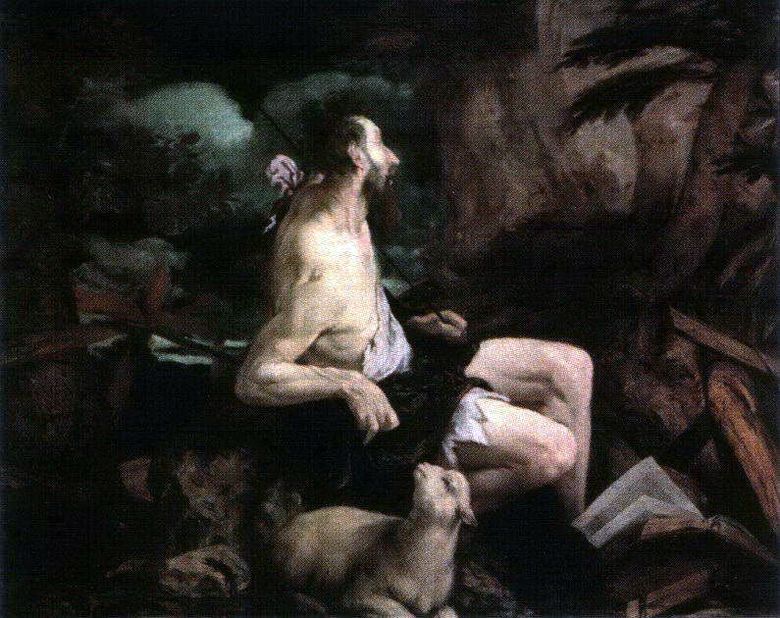

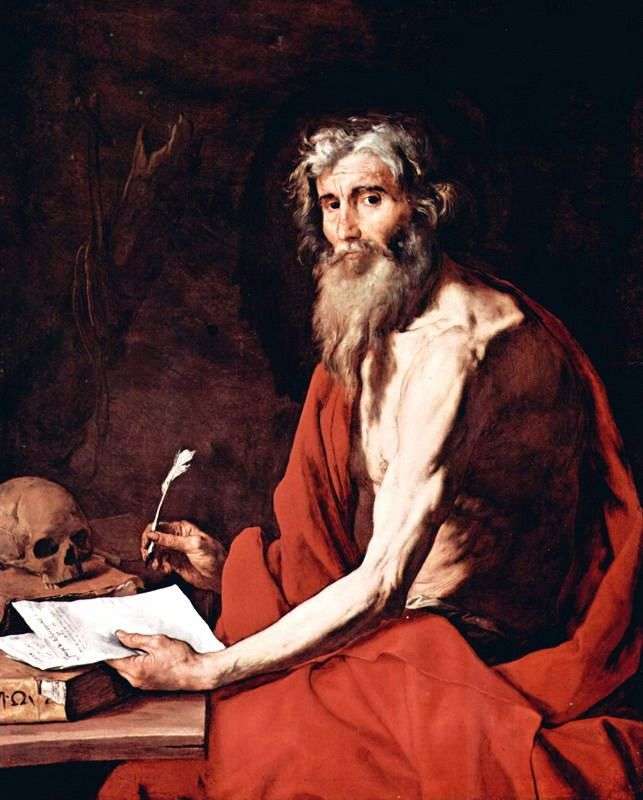

In the depiction of Jerome, the holy character of Christian history, the author of interpretations and polemic writings, an interpreter, it was customary to emphasize his remoteness from worldly vanity, from populated areas. Jerome lived for four years a hermit in the Chalcis desert near the Syrian city of Antioch. According to legend, he tortured himself before crucifixion with blows to the chest in tempting visions. In the desert, he learned Hebrew. In Rome, he was the secretary and assistant of Pope Damas I. It was on behalf of the pontiff that he translated from the Hebrew into Latin the books of the Old Testament, as well as the Gospels.

In 1546 at the Council of Trent, this translation of the Bible was declared canonical and was called the “vulgar”. As the author of the saint, vulgates are traditionally portrayed with a book, sometimes working in the study. Jacopo Bassano shows the old man repentant in the cave, with a stone in his hand, in front of an open book. Another attribute in the iconography of Jerome is the skull. However, here it is not “by the rules” located next to the foreground, illuminated by the same mystical light from the half-darkness, as the emaciated but not ascetic body of the elder. The crucifix looks absolutely marvelous. Nailed to the cross, the God-man is written as if alive, as if to the spectator, as to the learned and righteous Jerome, from afar, but the event itself appears personally.

Saint Jérôme dans le désert – Jacopo Bassano

Saint Jérôme dans le désert – Jacopo Bassano John the Baptist in the Desert by Jacopo Bassano

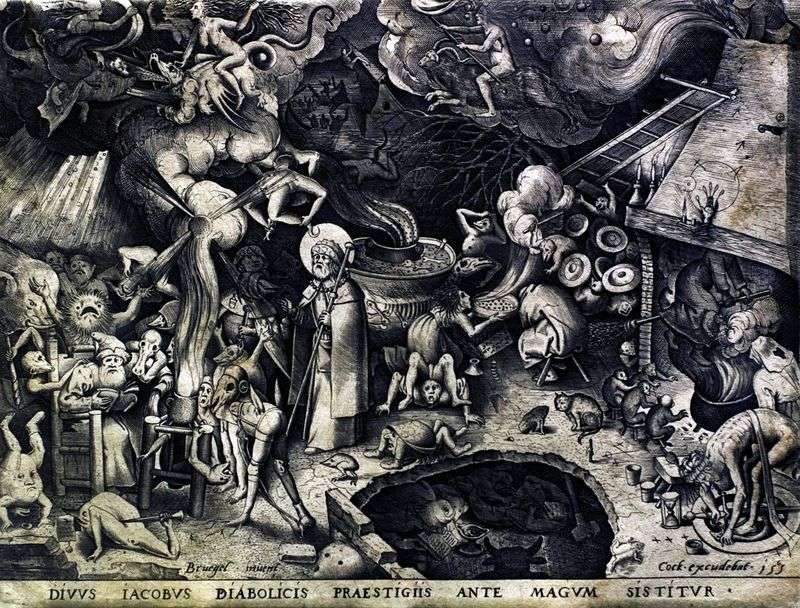

John the Baptist in the Desert by Jacopo Bassano Saint Jerome. Engraving by Peter Brueghel

Saint Jerome. Engraving by Peter Brueghel Jean-Baptiste dans le désert – Jacopo Bassano

Jean-Baptiste dans le désert – Jacopo Bassano The Prayer of St. Jerome by Hieronymus Bosch

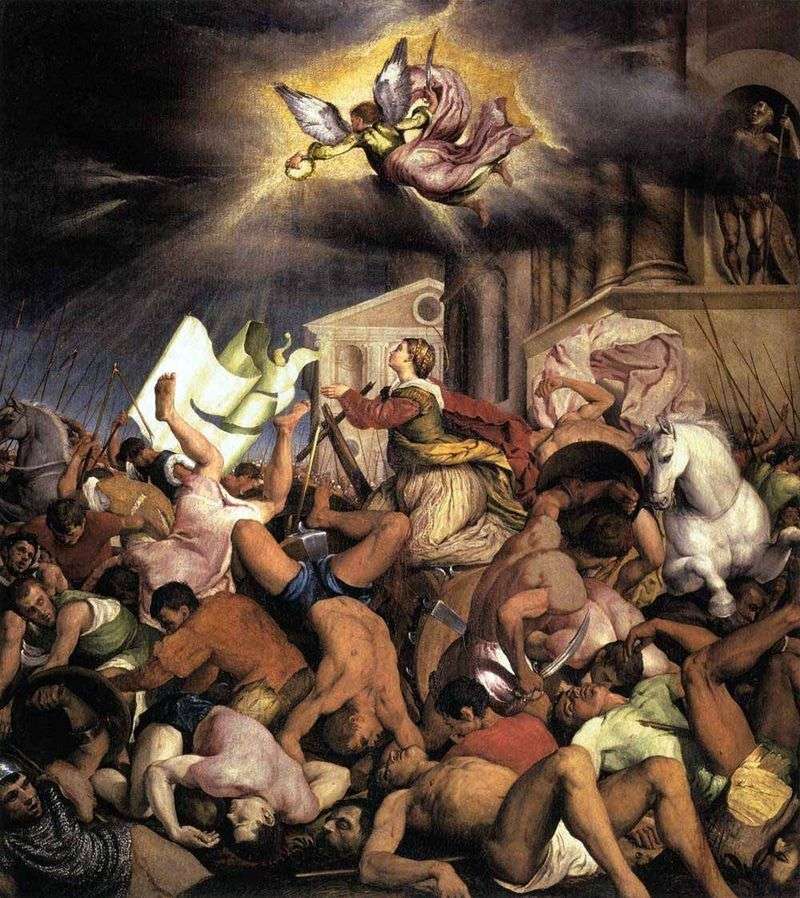

The Prayer of St. Jerome by Hieronymus Bosch The martyrdom of St. Catherine by Jacopo Bassano

The martyrdom of St. Catherine by Jacopo Bassano San Jerónimo en el desierto – Jacopo Bassano

San Jerónimo en el desierto – Jacopo Bassano Saint Jerome by Jusepe de Ribera

Saint Jerome by Jusepe de Ribera