In the early 1460s, the half-brothers Karl the Brave and Antoine of Burgundy, the sons of the famous Don Juan Philip the Good were sealed in portraits. After the death of van Eyck, the court painter was unofficially recognized as Rogier van der Weyden. Although many portraits of his brush were not preserved, among his customers were numerous aristocrats, rich merchants, high-ranking officials and church hierarchs. Among the upper class, it was considered a rule of good taste to have the images of their not always refined features, executed with a refined style.

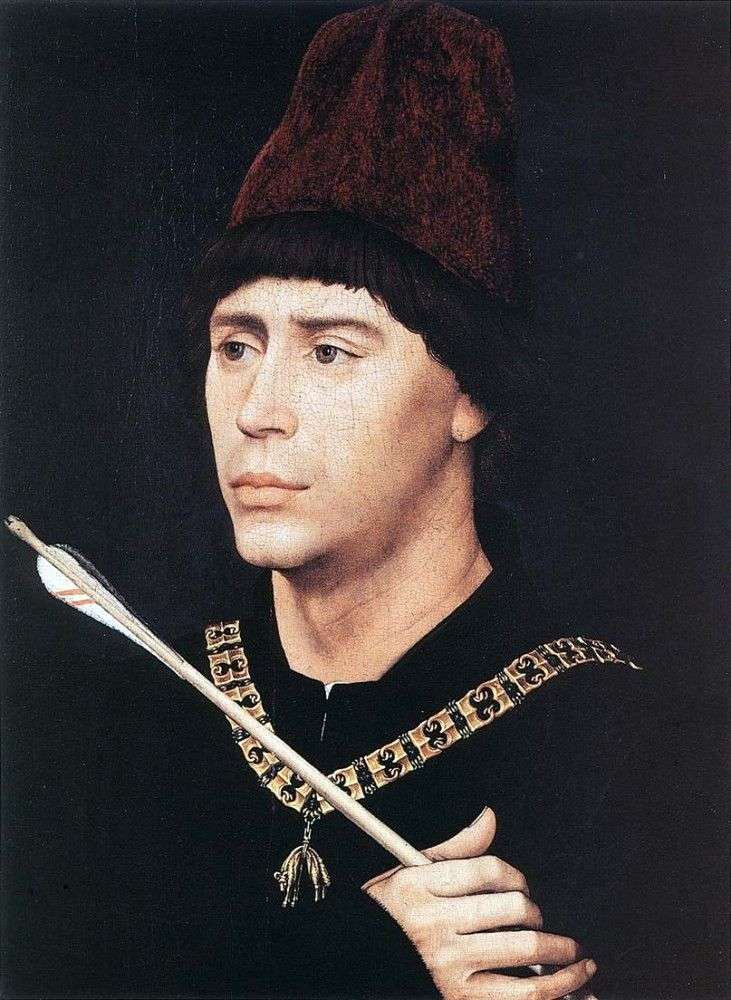

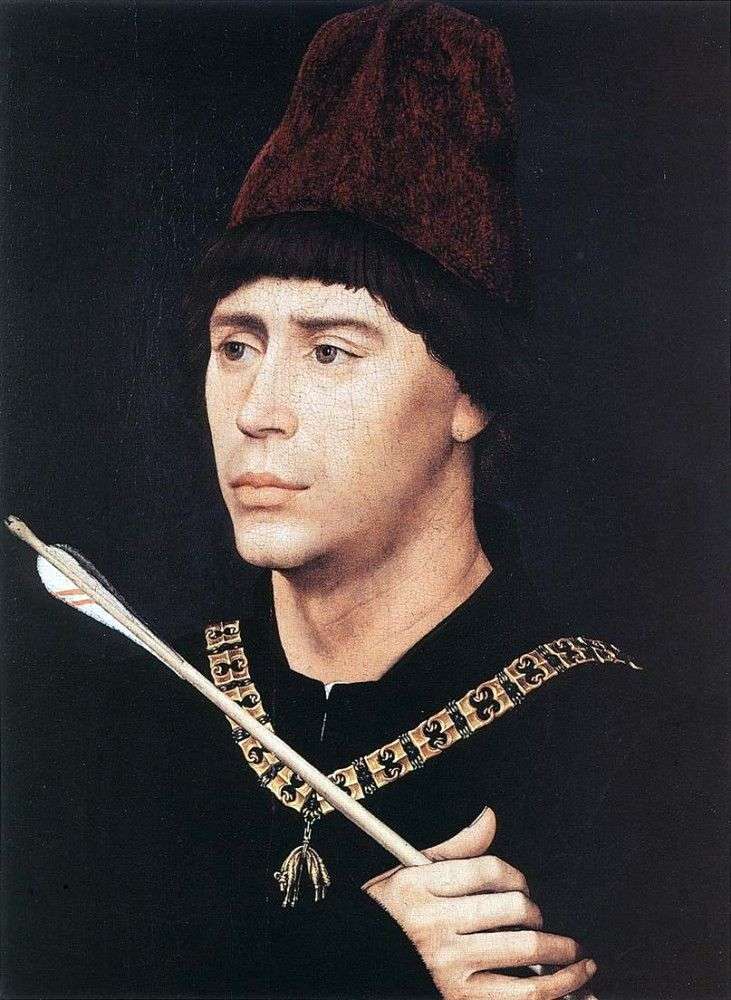

Quite often they were performed in the form of images for personal piety: a praying customer on one leaf, and the Virgin Mary or Christ on the other. For the representatives of the Duke’s family, the portrait was the official image. For example, a copy of the portrait of Duke Philip and his wife Isabella is known. Portrait of Antoine of Burgundy is by right considered the best surviving documented man’s portrait of van der Weyden. Antony is depicted in a purple-brown jacket with the same pattern as in the Berlin portrait of Charles the Bold.

Antoine is written on a homogeneous dark blue-green background. On his neck is the chain of the Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece; in the right hand pressed to his chest is a long arrow. His medium-length hair and high hood are a tribute to fashion, the peak of which came about 1467 and was expressed in long hair and high headdresses. In 1861, the Brussels Museum acquired the work as a portrait of Charles the Bold. Then the depicted knight was considered Antoine of Burgundy, then – Jacques de Laleng or John of Portugal. But relatively recently a portrait of the same man was discovered.

On its damaged back there are the remains of the emblem of the “great bastard of Burgundy,” as Antoine called it, the fortress tower from which the burning log is falling, and the second half of his motto: “ainsi le veul”. The arrow is a common knightly and military attribute, sometimes used as a ceremonial staff by tournament judges. Like the mace, it sometimes played the role of a symbol of power in the hands of rulers and nobles. The image of the hand on the portrait is amazing. It is not so much balancing the composition on this breast portrait, how much it attracts attention, like a second person. The hand itself is a whole work of art: it’s worth watching how the contours of the fingers go into the folds of the skin between them or match the crescent of the thumb with the flex of the little finger.

Equally expressive from this neighborhood is a straight shaft of arrows, although this is just an uncomplicated object. A person in a portrait reveals his rank rather than character. He is a symbol of civilization, not an individuality. In this vision lies the way of transferring the features of his face, from whose skin all possible defects are purposely removed: there are no wrinkles and scars, and lips seem literally polished. But at the same time, it is not so much a complete idealization, but an unduly manifested realism, limited in favor of the style and the whole image as a whole.

Antoine, the illegitimate son of Philip the Good and Jeanne de Presle, was born around 1430. In 1452 he was knighted, and in 1456 he was awarded the Order of the Golden Fleece. The repeated winner of tournaments, a brave warrior and collector of manuscripts, he served faithfully all his life to his father and half-brother Karl the Bold. After the latter’s death in 1477 he entered the service of the King of France. In 1504, Antoine died. His portrait, depicting Antoine at the age of about 30 years, one of the last works of the artist.

Portrait d’Antoine de Bourgogne – Rogier van der Weyden

Portrait d’Antoine de Bourgogne – Rogier van der Weyden Portrait of Chancellor Rolen and his wife by Rogier van der Weyden

Portrait of Chancellor Rolen and his wife by Rogier van der Weyden Portrait of Philip the Good by Rogier van der Weyden

Portrait of Philip the Good by Rogier van der Weyden Retrato de Antoine de Borgoña – Rogier van der Weyden

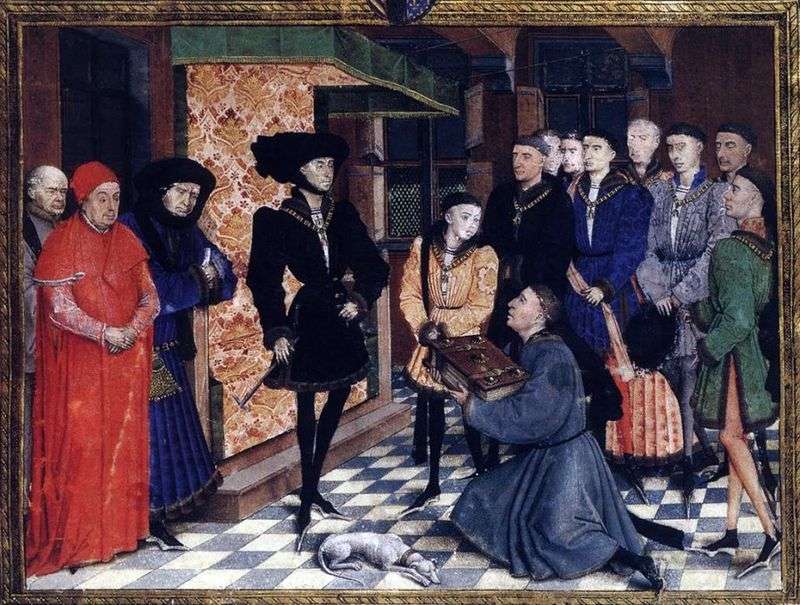

Retrato de Antoine de Borgoña – Rogier van der Weyden Chronicles of Hainaut by Rogier van der Weyden

Chronicles of Hainaut by Rogier van der Weyden Portrait du chancelier Rolen et de sa femme – Rogier van der Weyden

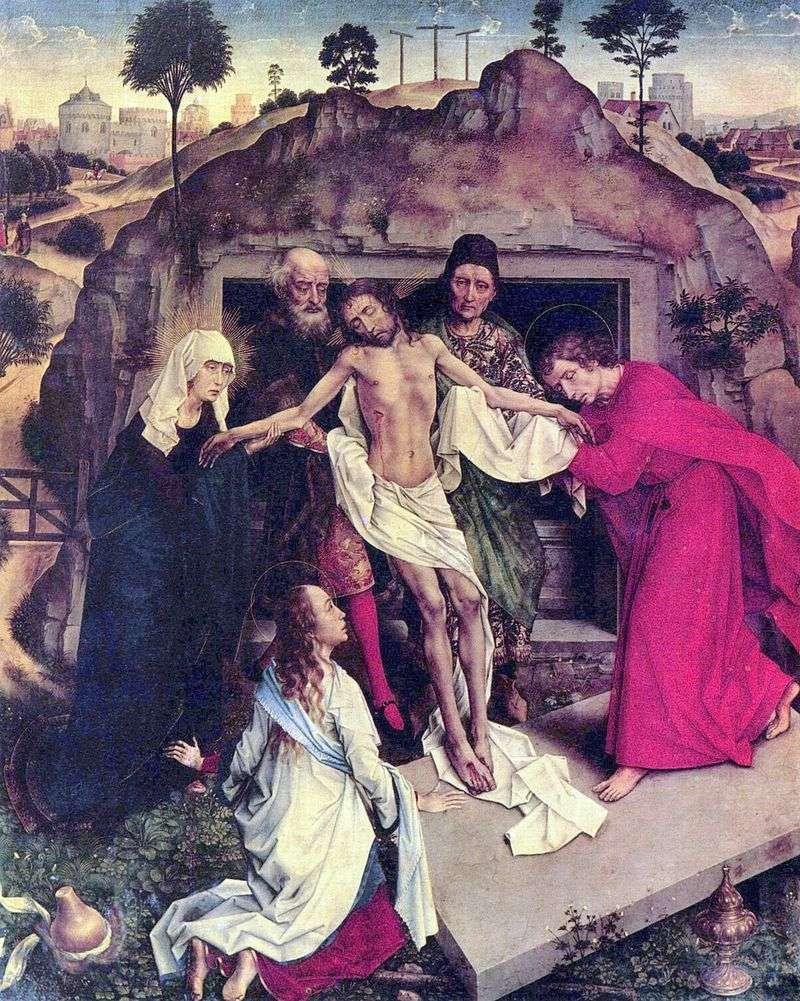

Portrait du chancelier Rolen et de sa femme – Rogier van der Weyden The situation in the grave by Rogier van der Weyden

The situation in the grave by Rogier van der Weyden Polyptych “The Last Judgment” by Rogier van der Weyden

Polyptych “The Last Judgment” by Rogier van der Weyden