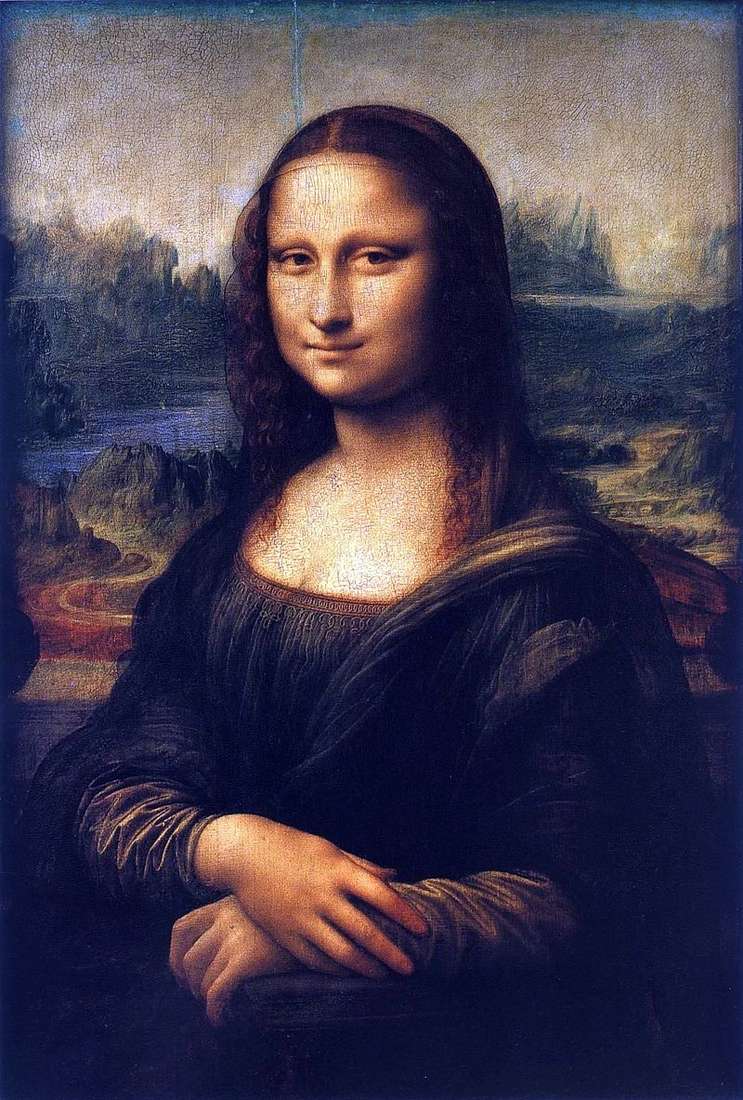

Painting by the artist Leonardo da Vinci “Mona Lisa” or “La Gioconda”. The size of the picture is 77 x 53 cm, wood, oil. About 1503, Leonardo began work on a portrait of the Mona Lisa, the wife of the rich Florentine Francesco Giocondo. This work, known to the common people under the name “Gioconda”, received an enthusiastic assessment already among contemporaries.

The glory of the painting was so great that later legends formed around it. It is devoted to a huge literature, much of which is far from an objective assessment of Leonard’s creation. One can not but admit that this work, as one of the few monuments of world art, really has a tremendous appeal. But this feature of the picture is not connected with the embodiment of some mysterious beginning or with other similar inventions, but is born by its striking artistic depth.

Portrait of Leonardo da Vinci “Mona Lisa” is a decisive step in the development of the Renaissance portrait art. Although the Quattrocento painters left a number of significant works of this genre, yet their achievements in the portrait were, so to speak, disproportionate to the achievements in the main pictorial genres – in compositions on religious and mythological themes. The unevenness of the portrait genre was felt already in the very “iconography” of portrait images. Actually portrait works of the 15th century, with all their indisputable physiognomic similarity and the feeling of inner strength radiated by them, differed in their external and internal stiffness. All that wealth of human feelings and experiences, which characterizes the biblical and mythological images of painters of the 15th century, was usually not the property of their portrait works. Echoes of this can be seen in the earlier portraits of Leonardo da Vinci, created by him in the first years of his stay in Milan. This is the “Portrait of a Lady with an Ermine”, depicting Cecilia Gallearani, beloved Ludovico Moro, and a portrait of a musician.

In comparison with them, the portrait of the Mona Lisa is perceived as the result of a giant qualitative shift. For the first time the portrait image in its significance has become one level with the brightest images of other pictorial genres. Mona Lisa is represented sitting in an armchair against the backdrop of the landscape, and the very comparison of her figure close to the viewer from the visible from afar, as if from a huge mountain landscape, gives the image an extraordinary grandeur. This impression is facilitated by the contrast of the increased plastic tactility of the figure and its smooth generalized silhouette with a foggy distance, a vision-like landscape with bizarre rocks and winding water channels among them. But first of all it attracts the face of the Mona Lisa herself – her unusual, as if watching the viewer, watching, radiating the mind and will, and a barely perceptible smile,

Little is found in the whole world of art portraits, equal to the picture “Mona Lisa” by the strength of the expression of the human person, embodied in the unity of character and intellect. It is the extraordinary intellectual charge of Leonardo’s portrait that distinguishes him from portrait images of quattrocento. This peculiarity is perceived as sharper, that it refers to the female portrait, in which the character of the model was first revealed in a completely different, mainly lyrical, imaginative tonality.

The sensation of strength coming from the painting “Mona Lisa” is an organic combination of inner concentration and a sense of personal freedom, the spiritual harmony of a person relying on his consciousness of his own significance. And the smile itself does not express superiority or neglect; it is perceived as the result of calm self-confidence and full self-control. But in the picture of Mona Lisa is embodied not only an intelligent beginning – the image of her is full of high poetry, which we feel in her elusive smile and in the mystery of the semi-fantastic landscape unfolding behind her. Contemporaries admired the artist’s amazing striking similarity and extraordinary vitality of the portrait. But its meaning is much broader: the great painter Leonardo da Vinci managed to bring into the image that degree of generalization, which allows us to consider it as an image of a Renaissance man in general. The feeling of generalization affects all the elements of the pictorial language of the picture, in its individual motifs – in how a light transparent veil, covering the head and shoulders of the Mona Lisa, unites carefully drawn strands of hair and fine folds of the dress in a common smooth contour; this feeling is incomparable in the soft modeling of the face and beautiful, sleek hands. This simulation causes such a strong impression of living corporeality that Vasari wrote that in the deepening of Mona Lisa’s neck one can see the beating of the pulse. combines the carefully written strands of hair and small folds of the dress in a common smooth contour; this feeling is incomparable in the soft modeling of the face and beautiful, sleek hands. This simulation causes such a strong impression of living corporeality that Vasari wrote that in the deepening of Mona Lisa’s neck one can see the beating of the pulse. combines the carefully written strands of hair and small folds of the dress in a common smooth contour; this feeling is incomparable in the soft modeling of the face and beautiful, sleek hands. This simulation causes such a strong impression of living corporeality that Vasari wrote that in the deepening of Mona Lisa’s neck one can see the beating of the pulse.

One of the means of such a subtle plastic nuance was the characteristic Leonard “sfumato” – a barely perceptible haze, enveloping the face and figure, softening the contours and shadows. Leonardo da Vinci recommends, for this purpose, to place between the source of light and bodies, as he puts it, “a sort of fog”. The predominance of the “cut-off” modeling is felt in the painting’s subordinate color. Like many works by Leonardo da Vinci, this picture has darkened from the time, and its color ratios have changed somewhat, but now well-considered comparisons in the tones of carnation and clothing and their overall contrast with the bluish-green, “submarine” tone of the landscape are clearly perceived.

Mona Lisa by Leonardo Da Vinci

Mona Lisa by Leonardo Da Vinci Mona Lisa ou Gioconda – Leonardo Da Vinci

Mona Lisa ou Gioconda – Leonardo Da Vinci Mona Lisa o Gioconda – Leonardo Da Vinci

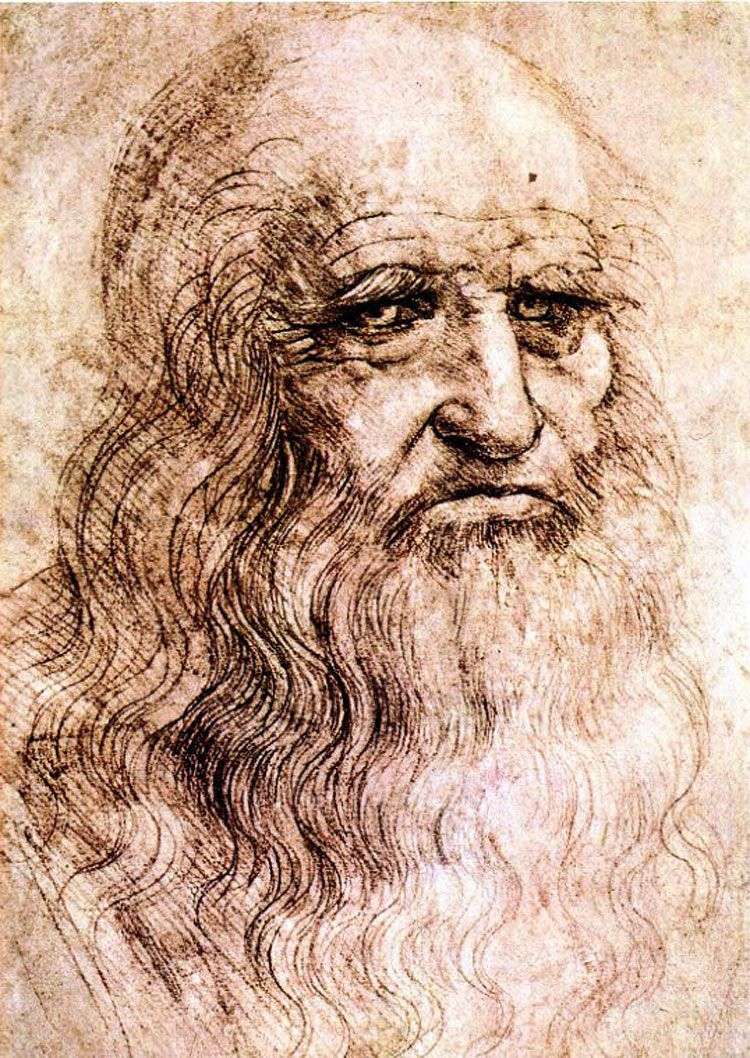

Mona Lisa o Gioconda – Leonardo Da Vinci Self Portrait by Leonardo Da Vinci

Self Portrait by Leonardo Da Vinci Bacchus by Leonardo Da Vinci

Bacchus by Leonardo Da Vinci Self-portrait by Leonardo Da Vinci

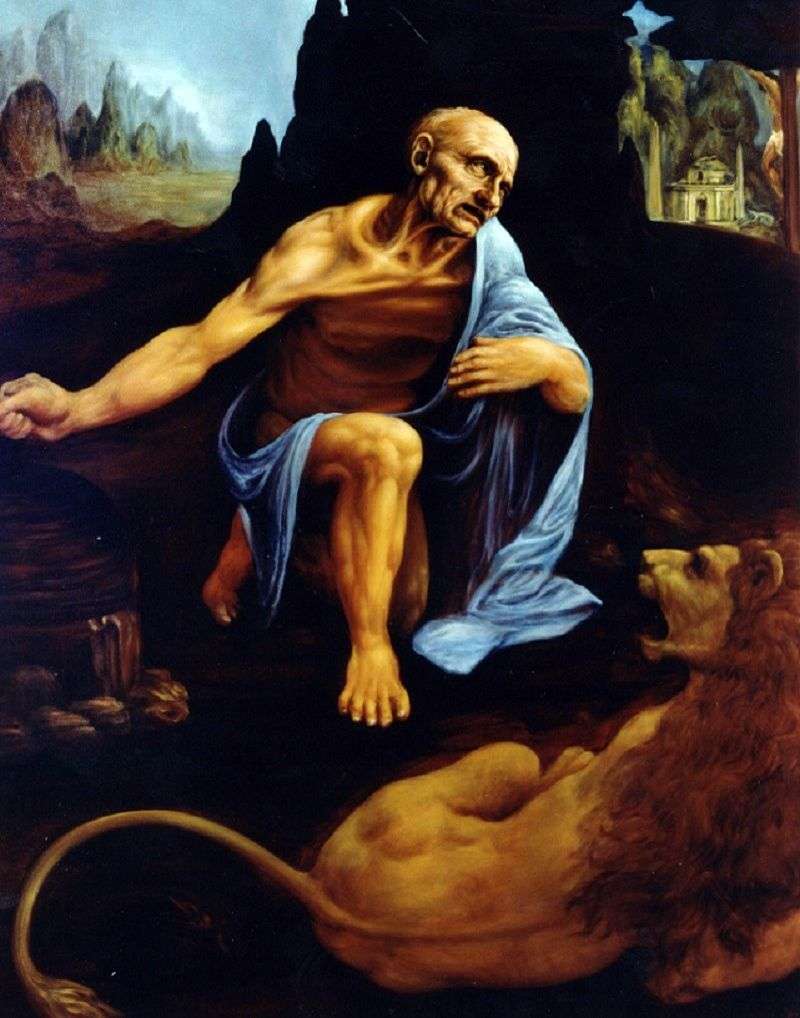

Self-portrait by Leonardo Da Vinci Saint Jerome by Leonardo Da Vinci

Saint Jerome by Leonardo Da Vinci Beautiful Ferronera by Leonardo Da Vinci

Beautiful Ferronera by Leonardo Da Vinci