In a confined space with an open window, from which you can see the winding Tuscan landscape – the river and the hills – Botticelli presented a group of figures in more complex compositional connection than the first samples of his “Madonna”.

The figures are now not so close. Maria with a slightly inclined head in sad melancholy touches the spikelet. The direction of her gaze is uncertain. Sitting on the lap of the Mother, a serious Baby lifted his hand in a gesture of blessing.

A young angel with a sharply pointed oval face and not childish wisdom – an unusual image for the early Botticelli. He holds out to the little Christ a vase with grapes and grain ears.

Grapes and ears – wine and bread symbolic image of the sacrament, the future sufferings of the Lord, His Passion. According to the artist, they should make up the semantic and compositional center of the picture that unites all three figures. Leonardo da Vinci set himself a similar task.

In the near future “Madonna Benois.” In it, Mary holds out to the child a flower of the crucifix – a symbol of the cross. But Leonardo needs this flower only in order to create a clearly tangible psychological connection between the mother and the child; he needs an object on which he can equally concentrate the attention of both and give purpose to their gestures. Botticelli’s vase with grapes also completely absorbs the attention of the characters. However, it does not unite, but rather internally disunites them; looking at her thoughtfully, they forget each other.

In the picture there is an atmosphere of deep thoughtfulness, detachment, inner disunity of characters. This is largely facilitated by the nature of the lighting, smooth, scattered, almost without giving shadows. Transparent light Botticelli does not have a spiritual intimacy, intimate communication, while Leonardo creates the impression of twilight: they envelop the heroes, leave them alone with each other.

Madonna with the Child and John the Baptist by Sandro Botticelli

Madonna with the Child and John the Baptist by Sandro Botticelli Madonna with the Child and the Five Angels by Sandro Botticelli

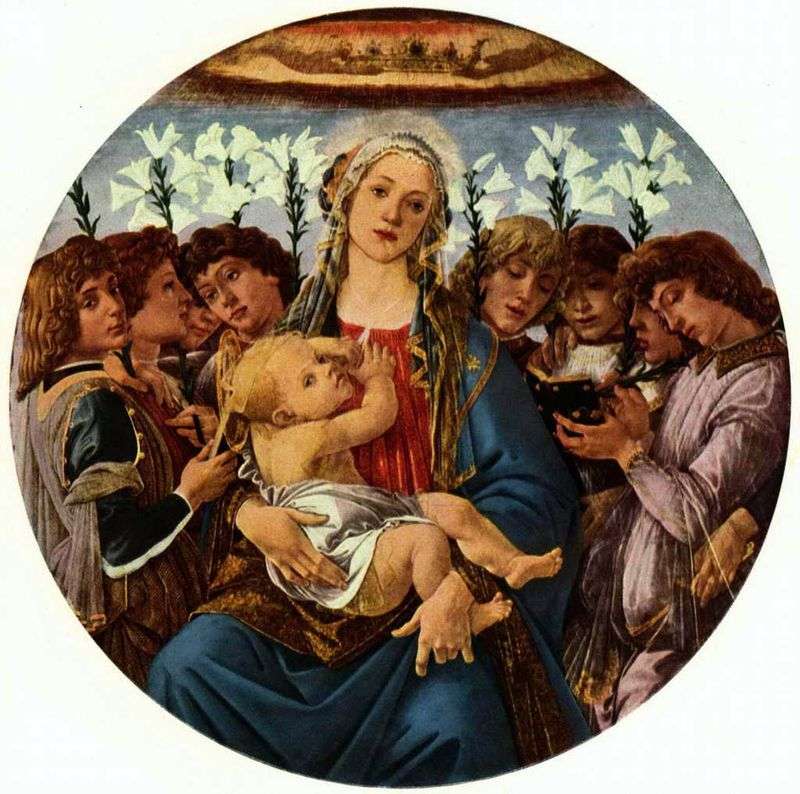

Madonna with the Child and the Five Angels by Sandro Botticelli Madonna with the Child and the Eight Angels (Rachin Tondo) by Sandro Botticelli

Madonna with the Child and the Eight Angels (Rachin Tondo) by Sandro Botticelli Madonna Magnificat by Sandro Botticelli

Madonna Magnificat by Sandro Botticelli Madonna with a book by Sandro Botticelli

Madonna with a book by Sandro Botticelli Madonna in glory by Sandro Botticelli

Madonna in glory by Sandro Botticelli Madonna with Child, Angels and Saint John the Baptist by Sandro Botticelli

Madonna with Child, Angels and Saint John the Baptist by Sandro Botticelli Madonna under the canopy (Madonna del Padillone) by Sandro Botticelli

Madonna under the canopy (Madonna del Padillone) by Sandro Botticelli