This masterpiece of Giotto is the pearl of the Capilla del Arena. The center of the composition are two close faces: the dead Christ and His Mother. It is here that the spectator’s eye is guided by the stone slope and the views of the other participants in the scene. A very expressive posture of the Virgin, bending over Christ and staring unceasingly at the lifeless face of the Son. The emotional tension of this “picturesque” story is unprecedented – we will not find analogs to it in the then painting.

Symbolic here is the “landscape”. The stone slope divides the picture diagonally, emphasizing the depth of the fateful loss. The figures around the body of Christ express their various emotions in their postures and gestures. We see before us the stoically worried Mount Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathea, sobbing Mary Magdalene, clinging to the feet of Christ, women wringing their hands in despair, and mourning the death of the Savior of the angels. This masterpiece of Giotto in a concentrated form demonstrates the innovative nature of his painting. The break with Byzantine tradition, which prevailed in medieval art, is sharply marked here. This applies to absolutely everything. The sacred plot turns into a living narrative.

It is Giotto’s painting that ceases to be only an auxiliary commentary on the Holy Scripture, gaining independent significance. The artist departs from stereotypes, abandons the rigid symbolic system, he is interested in complex spatial and optical effects. He is interested in the world in its diversity. He, finally, is interested in the truth of human feelings and human thought. His characters lose their former iconic shape – they – stocky, broad, endowed with majestic appearance, dressed in clothes and raincoats simple cut of the heavy, plain fabric, draped in large folds. Boccaccio wrote that the artist’s characters are perfectly alive people, they just can not talk.

The most important role in Giotto begins to play color. He not only expresses not so much the heavenly symbolism, but helps to give real convincingness, plasticity to figures and objects, to highlight the main characters, to reveal the ideological meaning of the composition. In his compositions, Giotto analyzes the soul of a person, analyzes his feelings, shows various aspects of his character, his moral state. He depicts religious scenes in an earthly setting, instead of the golden soil of the Byzantines, he has a landscape or buildings.

Some of the scenes Giotto borrows from Byzantine art, but recycles them, reviving a new life. Yes, for today’s taste, the artist acts at times very insecure. But the way is planned. And this way will lead to the higher Renaissance ups. It seems that Giotto and, say, Michelangelo can not even be compared, but Michelangelo, whom we know, would never have been, do not make Giotto these uncertain, in our opinion, steps.

The first steps towards a new art Michelangelo himself understood this well, appreciating the merits of his predecessor. And the assessments of other great contemporaries and close descendants speak volumes. They talk about the shock they experienced from the paintings of Giotto. Let’s call Dante, Boccaccio. Let’s call the same Vasari.

The Last Supper by Giotto

The Last Supper by Giotto Lamentation of Christ by Giotto di Bondone

Lamentation of Christ by Giotto di Bondone Pieta, or Lamentation of Christ by El Greco

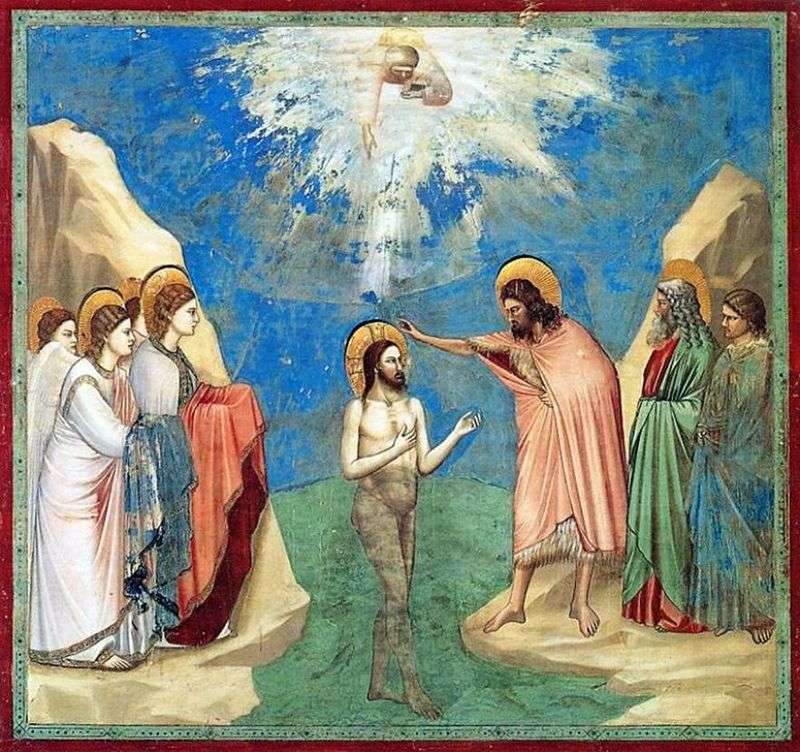

Pieta, or Lamentation of Christ by El Greco The Baptism of Christ by Giotto

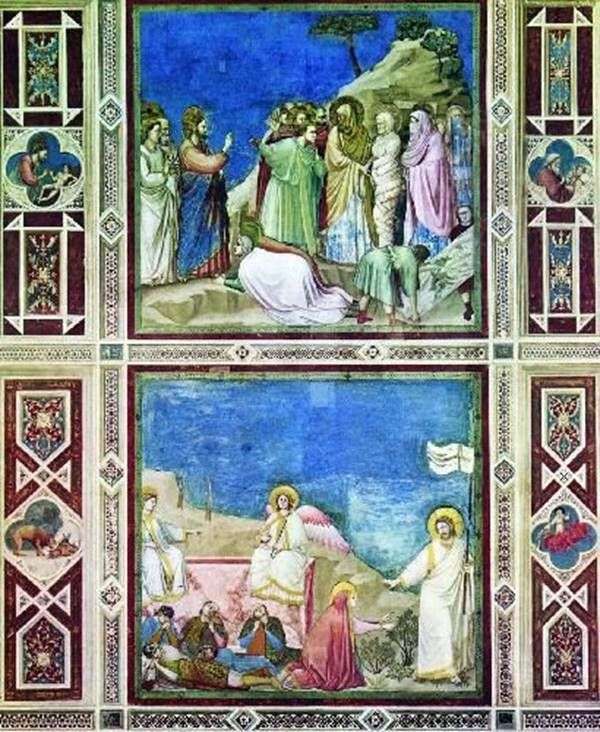

The Baptism of Christ by Giotto Paintings of the Capella del Arena by Giotto di Bondone

Paintings of the Capella del Arena by Giotto di Bondone Marriage in Cana of Galilee by Giotto

Marriage in Cana of Galilee by Giotto Escape to Egypt by Giotto

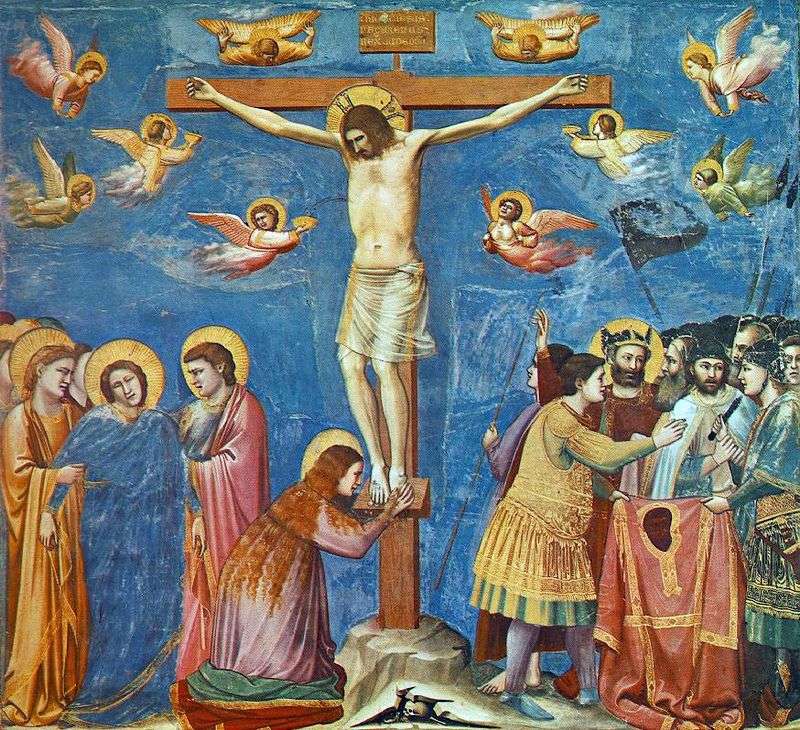

Escape to Egypt by Giotto Crucifixion (Capella del Arena) by Giotto

Crucifixion (Capella del Arena) by Giotto