Painting of the artist Tiziano Vecellio “The situation in the grave.” The size of the picture is 148 x 205 cm, canvas, oil. Titian of this period was not alien to the themes of a dramatic nature, which was natural amidst that strength of forces, in the difficult struggle that Venice had recently experienced.

Obviously, the experience of this heroic struggle and the trials connected with it in many ways contributed to the achievement of that full manly strength and mournful greatness of pathos that was embodied by Titian in his Louvre “Position in the Coffin.” The beautiful and powerful body of the dead Christ conjures up in the imagination of the viewer the notion of the courageous fighter-hero who fell in battle, and not at all about the voluntary sufferer who gave his life for the redemption of human sins.

The restrained hot coloring of the picture, the power of the movements and the strength of the feeling of strong courageous people carrying the body of the fallen, the very compactness of the composition in which the figures brought to the fore fill the entire plane of the canvas, give the picture the heroic sounding so characteristic of the art of the High Renaissance.

In this work, with all its dramaticness, there is no feeling of hopelessness, of internal breakdown. If this is a tragedy, then, in modern terms, it is an optimistic tragedy that glorifies the strength of the spirit of a person, his beauty and nobility, and in suffering. This distinguishes it from the complete hopeless grief of the later, Madrid’s “Position in the Casket.”

In the Louvre “Position in the Coffin” and especially in the death of the “Murder of St. Peter the Martyr” in 1867, a new step achieved by Titian in transmitting the connection between the mood of nature and the experiences of the depicted heroes is noteworthy. Such are the sombre and formidable tones of the sunset in the “Position in the Coffin,” the violent whirlwind, the shaking trees, in “The Murder of St. Peter,” so consonant with this explosion of merciless passions, the fury of the murderer, Peter’s despair.

In these works, the state of nature is, as it were, caused by the actions and passions of people. In this respect, the life of nature is subordinate to a person who still remains “the master of the world”. Later, in the late Titian, the life of nature, as the embodiment of the chaos of the spontaneous forces of the universe, acquires a force of existence independent of man and often hostile to him.

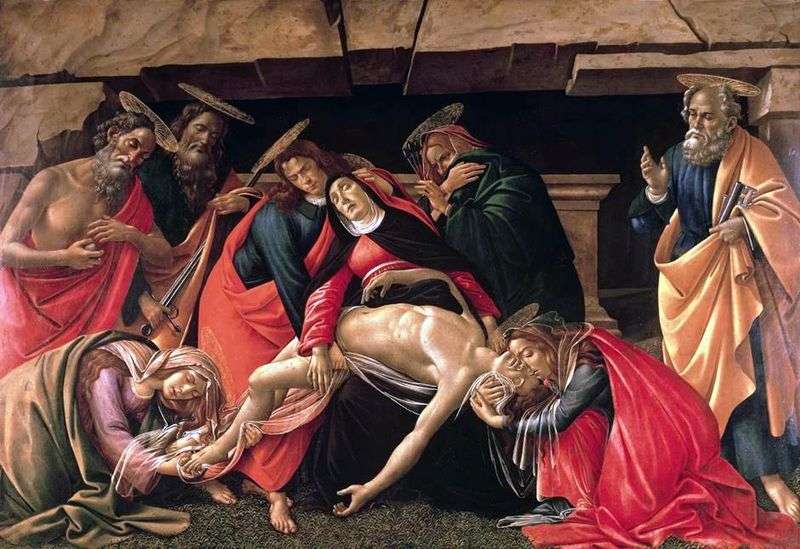

The situation in the grave is Sandro Botticelli

The situation in the grave is Sandro Botticelli Dinner at Emmaus by Tician Vecellio

Dinner at Emmaus by Tician Vecellio Secular love by Titian Vecellio

Secular love by Titian Vecellio The situation in the grave by Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

The situation in the grave by Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio Lamentation of Christ (Pieta) by Titian Vecellio

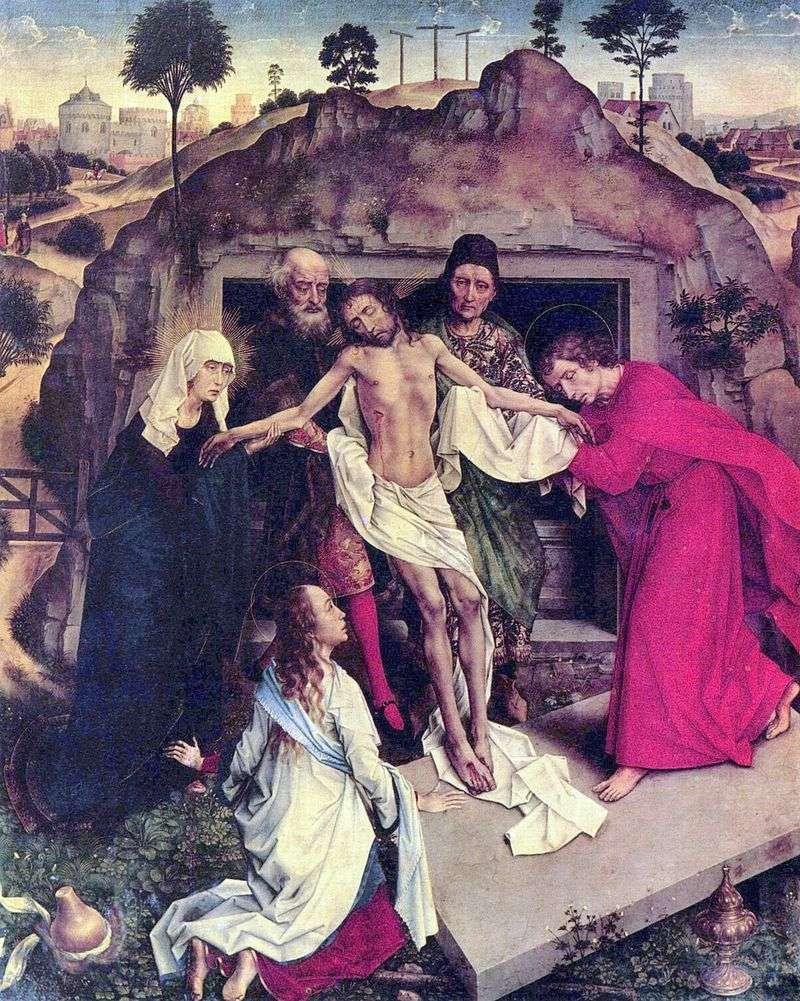

Lamentation of Christ (Pieta) by Titian Vecellio The situation in the grave by Rogier van der Weyden

The situation in the grave by Rogier van der Weyden The situation in the coffin by Hans Holbein

The situation in the coffin by Hans Holbein Danae by Titian Vecellio

Danae by Titian Vecellio