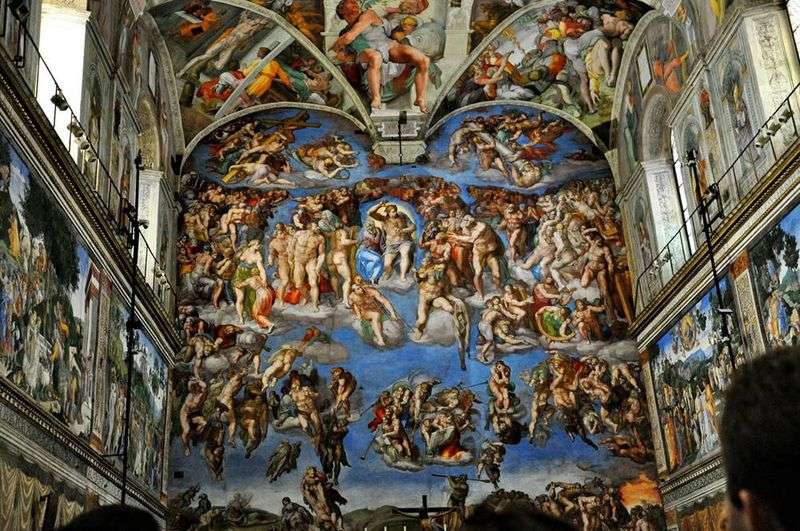

The Sistine Chapel was built in 1475-81, during the time of Pope Sixt IV, and the walls are still decorated with frescoes by remarkable masters of the time. The arch was originally depicted with a sky covered with stars, and in 1508 Pope Julius II ordered thirty-three-year-old Michelangelo to paint it.

The artist did the truly impossible: in four years he wrote on a 600-square-meter ceiling. m more than 300 figures in the most difficult angles! Moreover, the technique of the so-called “clean fresco”, painting on wet plaster, is very complex, because it requires speed and precision from the master. We add that Michelangelo worked in an extremely uncomfortable position – lying on a specially designed platform, constantly wiping paint that dripped on his face. He painted the vault almost alone: apprentices were entrusted with only minor details of the frames.

For each figure, the artist made many sketches and a life-size sketch, but it was still impossible to assess the unity of the composition, as long as the work was closed by the scaffolding. The more striking is the perfection of the fresco! Michelangelo – not only a sculptor, painter, architect, but also a wonderful poet – was a sensitive reader of the Bible, and the compositional form he found surprisingly accurately reflects the very mosaic structure of the Old Testament, which arose over the centuries, consisting of many books that, differing greatly from other stylistically, add up, nevertheless, into one monumental whole.

All parts of the fresco, whether the storyline scene or a separate figure, are finished and self-sufficient, but they naturally merge into the overall composition, subject to a single rhythm, and the repeating elements of the frame – figures of naked youths, medallions and architectural details – liken the pattern to a complex ornament, as if woven from human bodies. The man is not just the main, but the only subject of Michelangelo’s sculptural and pictorial works. Unlike other masters of the Renaissance, for whom a keen interest in man did not exclude attention to what surrounds him – nature, architecture, the world of things, Michelangelo knew only one means of expression: the plastics of the human body.

In the paintings of the Sistine Chapel, the landscape, interiors, clothing, objects are present minimally, only where it is impossible to do without them; they are generalized, not detailed and do not distract from the narration of human deeds, characters, passions. Such an artist’s focus on the main thing could not be more than match the style of biblical stories, in which the dramatic plots are summarized, in a few mean, epic-capacious phrases, and this concentration of feelings is much more impressive than another flowery story.

The language of plastics – the language of line, form, color – sounds in Michelangelo as powerfully, succinctly and sublimely as the verses of the Bible; The pathos of the Book of Books is embodied so naturally, convincingly and freely, that any other interpretation of familiar plots seems to be impossible. The book of Genesis corresponds to nine compositions that occupy the entire central field of the vault. To familiarize yourself with them in the sequence in which the plots are set forth in the Bible, one must go to the altar and begin the inspection, moving from it to the entrance.

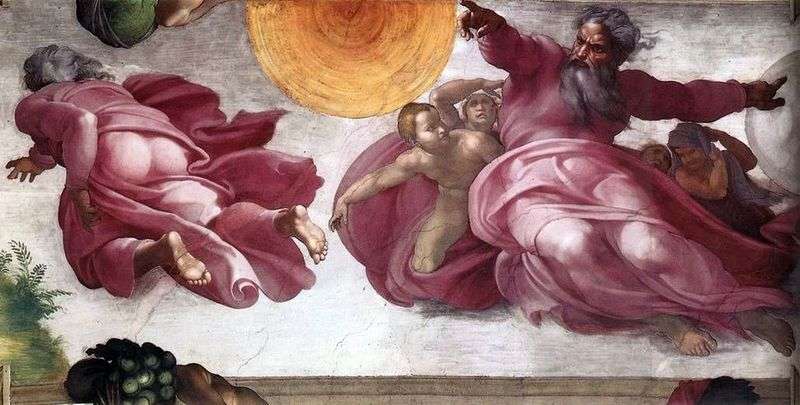

Five scenes are devoted to the creation of the world: “Separation of light from darkness”, “Creation of the luminaries and plants”, “Separation of firmament from water”, “Creation of Adam”, “Creation of Eve”. It seems that it was in these compositions that Michelangelo put the most personal into himself – who, if not him, the obsessed sculptor, was close to the pathos of creation! Combat with inert matter, create new beautiful bodies from a shapeless, inanimate mass, sculpt them from clay, carve out of stone – this inspired work most of all attracted the master: it was not without reason that he compared sculpture to the sun, and painting to the moon.

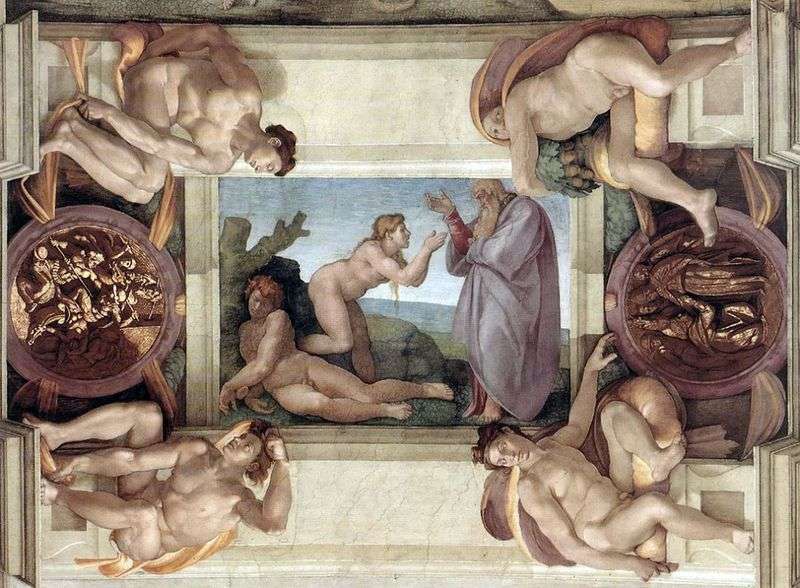

The author of the famous frescoes always felt first and foremost a sculptor, often repeating: “Painting is not my craft.” And Michelangelo God appears before us the victorious chaos of the Sculptor of the Universe. The face of Savaof is almost distorted by the torments of creativity, then beautiful in its concentration. His powerful muscular body, the hands of his strong sensitive hands radiate energy. God does not need to touch his creations – they obey his confident free gestures. In the Separation of Light from Darkness, Sabaoth spreads shapeless clouds of fog to the sides, and we seem to hear the noise of a great peace-building. With strong strokes of hands, he sends luminaries to the sky, gives life to plants, pacifies the water element, and with a majestic movement removes the feminine and submissive Eve from Adam’s ribs.

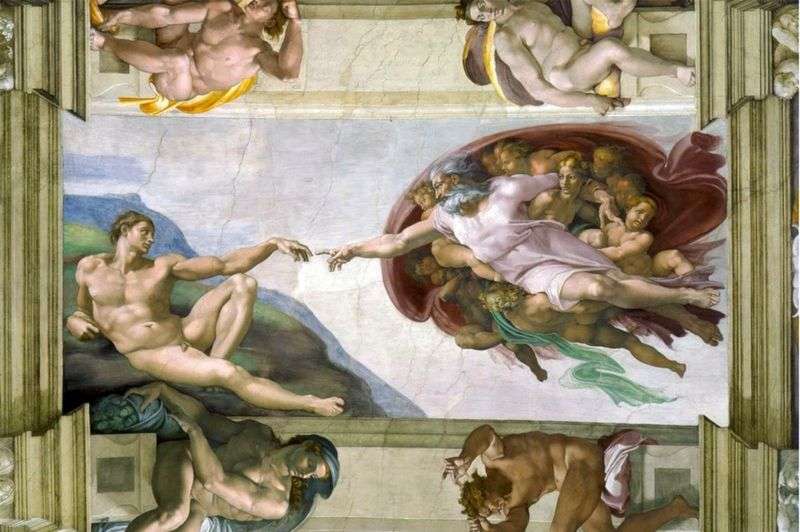

In Adam’s Creation, admittedly, the finest composition of the entire mural, from the imperious hand of Savaof to the still limp, quivering brush of the first man, a stream of life-giving force almost visibly emanates; and it is hardly possible to find in the world art a more accurate formula of “creativity and miracles,” a more capacious metaphor for the unity of material and spiritual, earthly and heavenly, than these two aspiring, almost touching hands. Shortly before his death, Michelangelo destroyed all his rough sketches and sketches – he didn’t want his descendants to “see his sweat”, and when we look at the vault of the Sistine Chapel, it seems to us that the greatest of earth artists created his Universe in no more than six days.

The Creation of Eve by Michelangelo Buonarroti

The Creation of Eve by Michelangelo Buonarroti Flood, a fragment of the painting of the Sistine Chapel (fresco) by Michelangelo Buonarroti

Flood, a fragment of the painting of the Sistine Chapel (fresco) by Michelangelo Buonarroti The Creation of Adam by Michelangelo Buonarroti

The Creation of Adam by Michelangelo Buonarroti Creation of Adam by Michelangelo

Creation of Adam by Michelangelo The Last Judgment by Michelangelo Buonarroti

The Last Judgment by Michelangelo Buonarroti Persian Sibyl (fresco) by Michelangelo Buonarroti

Persian Sibyl (fresco) by Michelangelo Buonarroti The Delphic Sibyl by Michelangelo Buonarroti Buonarroti

The Delphic Sibyl by Michelangelo Buonarroti Buonarroti The Fall and Exile from Paradise by Michelangelo Buonarroti

The Fall and Exile from Paradise by Michelangelo Buonarroti