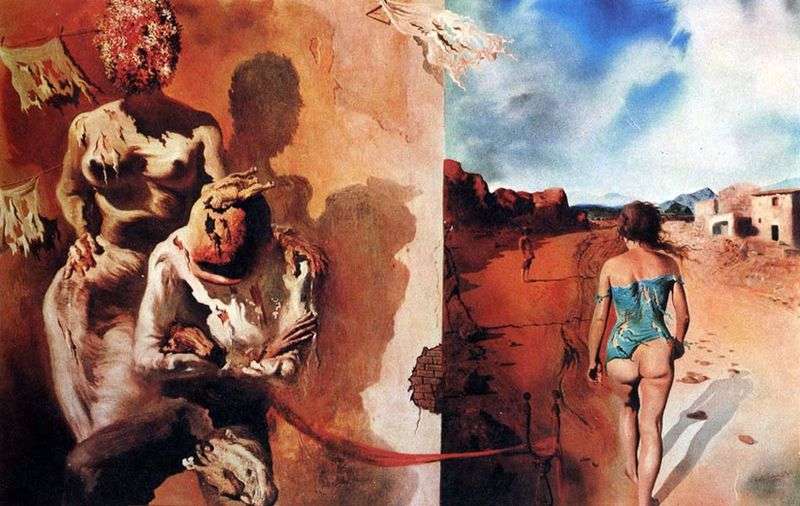

The horizontal fabric is divided into two unequal parts. In the color scheme of the picture, shades of ocher predominate. The right, the smaller half of the canvas, is the dream space. There, to the reddish ohristy tones is added and azure, giving this fragment the volume and depth.

In front of the viewer there is a typical southern landscape: mountains in the distance, ordinary-looking houses, dusty dirt road. On the way there is a woman in tattered remnants of a blue swimsuit or blouse. There is no other clothing for the woman. The viewer sees her from the back: naked buttocks, tangled hair, waving in the wind.

In the background one more female figure is seen: in clothes, in a hat. The left side of the picture is the dream allegory as a phenomenon. The background is an unevenly plastered wall. Where the plaster peeled off, brickwork is visible. In places, nails are pinned to the wall and fragments of cloth torn in rags fluttering in the wind are hung on ropes. One of these rags is present immediately in both halves of the canvas. The wind unites both parts of the composition: the woman’s hair and cloth tapes, torn from her clothes, flutter in the same direction as the flaps on the left side of the picture.

In the foreground we see a bent male figure. The man kneels in a constrained, constrained position. His hands are crossed on his chest, his head is lowered, his face is not visible. On his head is a kepi with a visor, decorated with chicken carcass on top. Behind the man, laying his hand on his shoulder, rises a tall, stately woman. It has magnificent forms, its hips are draped with a thin cloth, the breast is exposed. Instead of a head, this creature is crowned with something that resembles a sea sponge. These two are brightly lit, their shadows stand out clearly on the wall.

From the belly of a man, from under his crossed arms stretches a ribbon of red cloth that goes to the next location, into the space of sleep. There it hangs down to the ground, picked up by a split crutch-prop, Dali’s favorite attribute. The picture is not imbued with an underlying, even explicit, naked eroticism. A ribbon, thrown from one part of the canvas to another, from a man to a woman, is interpreted by art historians as an allegory of a nocturnal pollination.

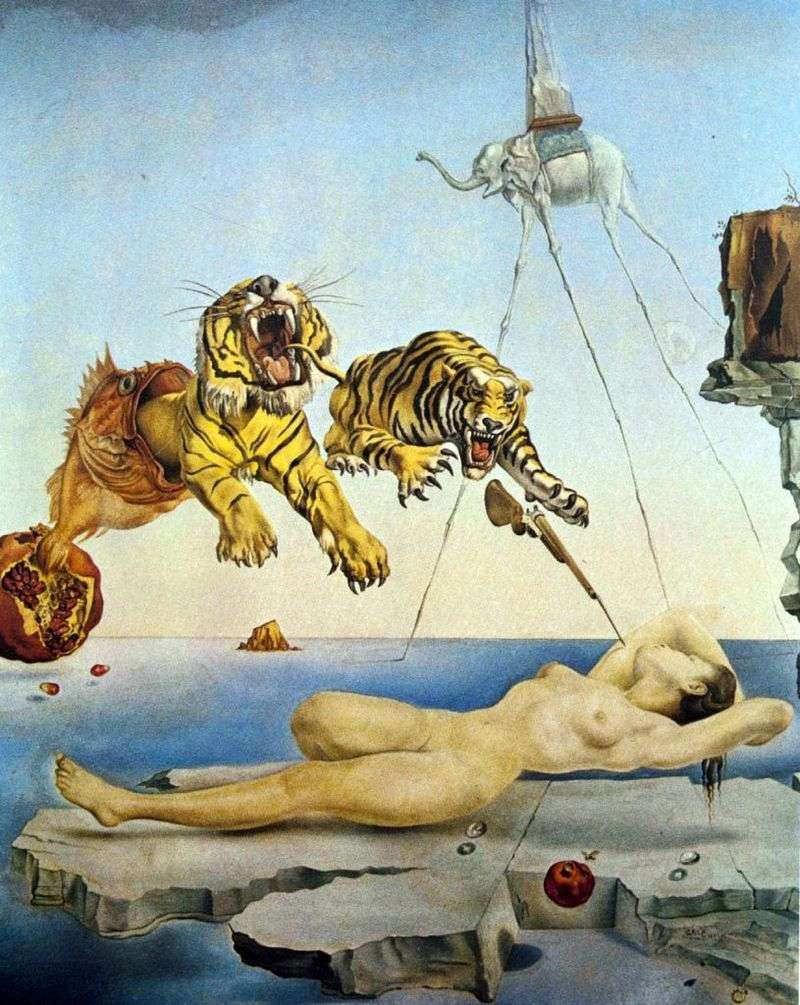

Sleep caused by flight of a bee around a pomegranate a second before awakening by Salvador Dali

Sleep caused by flight of a bee around a pomegranate a second before awakening by Salvador Dali Sleep (Sleeping) by Salvador Dali

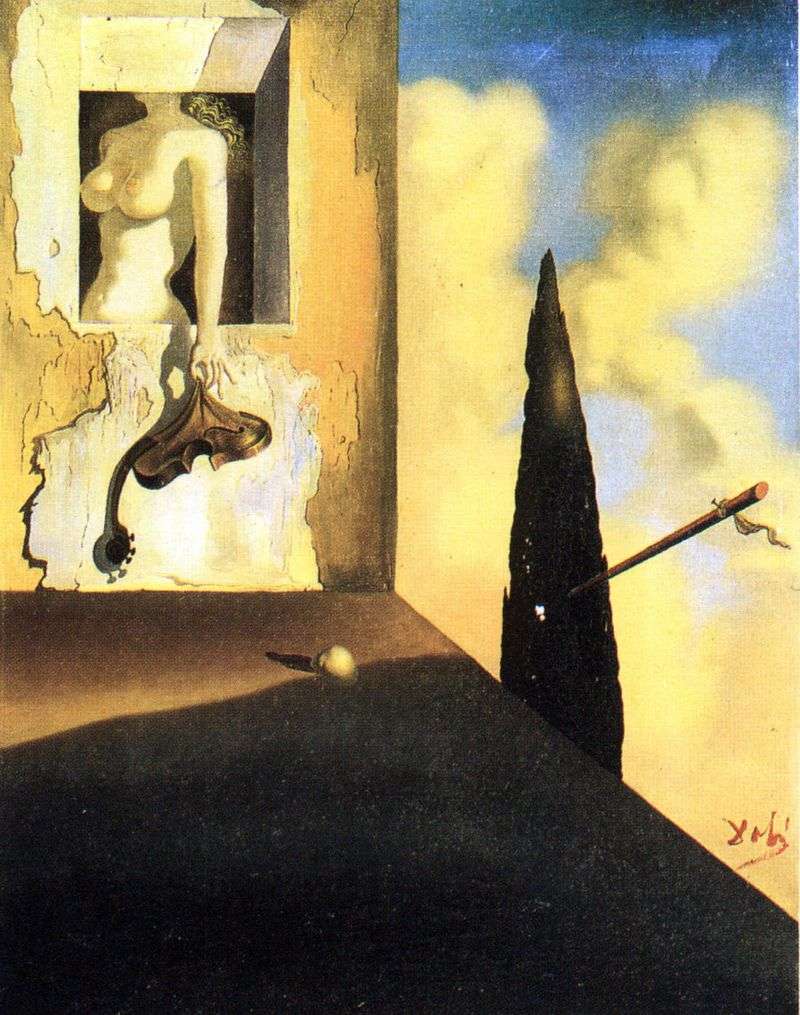

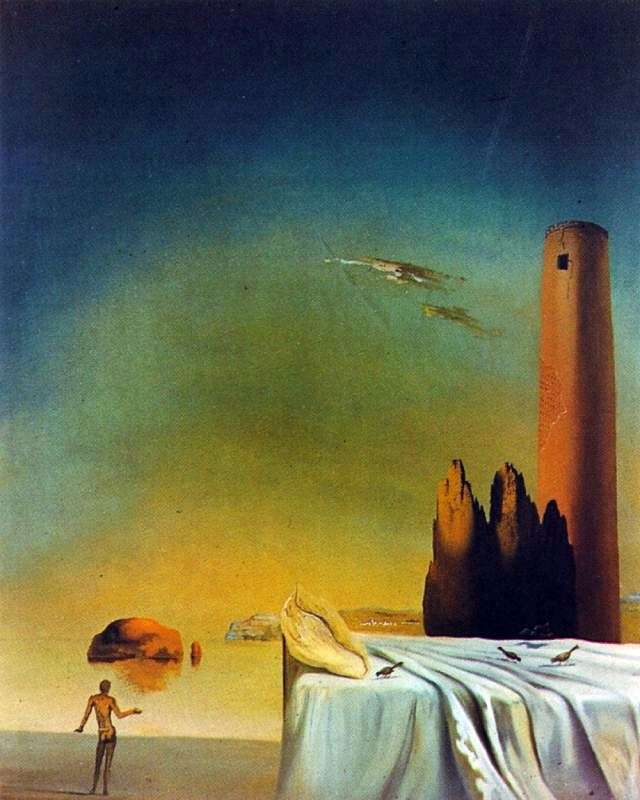

Sleep (Sleeping) by Salvador Dali Anxious sign by Salvador Dali

Anxious sign by Salvador Dali Masochistic tool by Salvador Dali

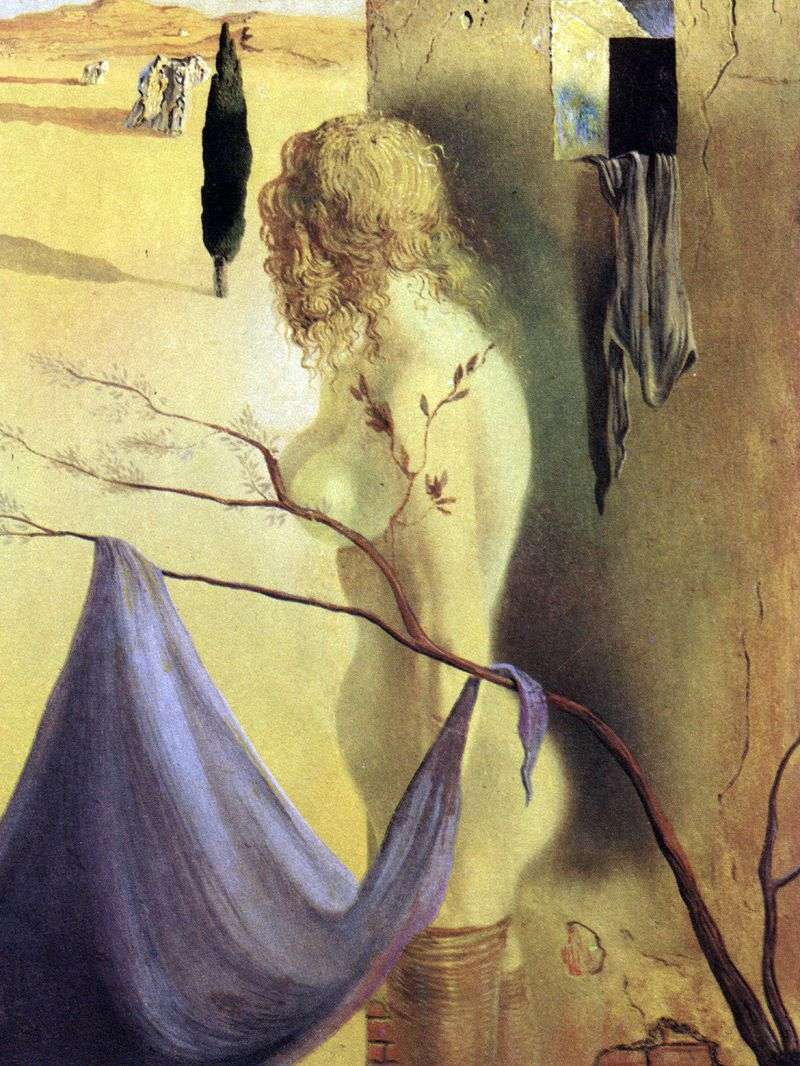

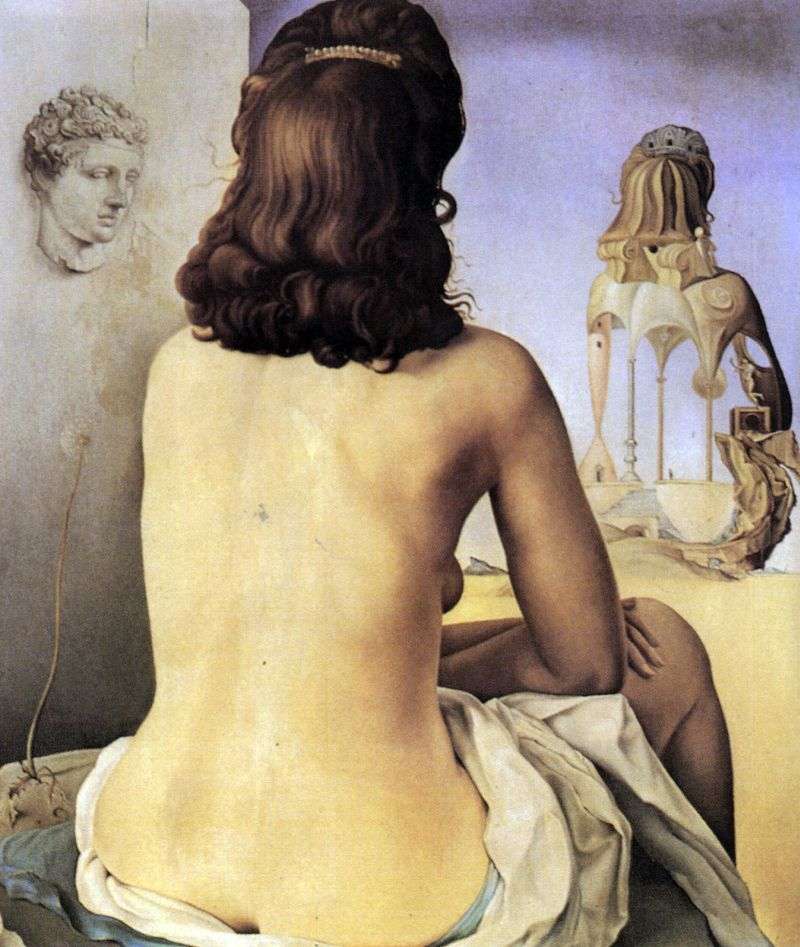

Masochistic tool by Salvador Dali My wife, naked, looks at her own body by Salvador Dali

My wife, naked, looks at her own body by Salvador Dali Sleep approaches by Salvador Dali

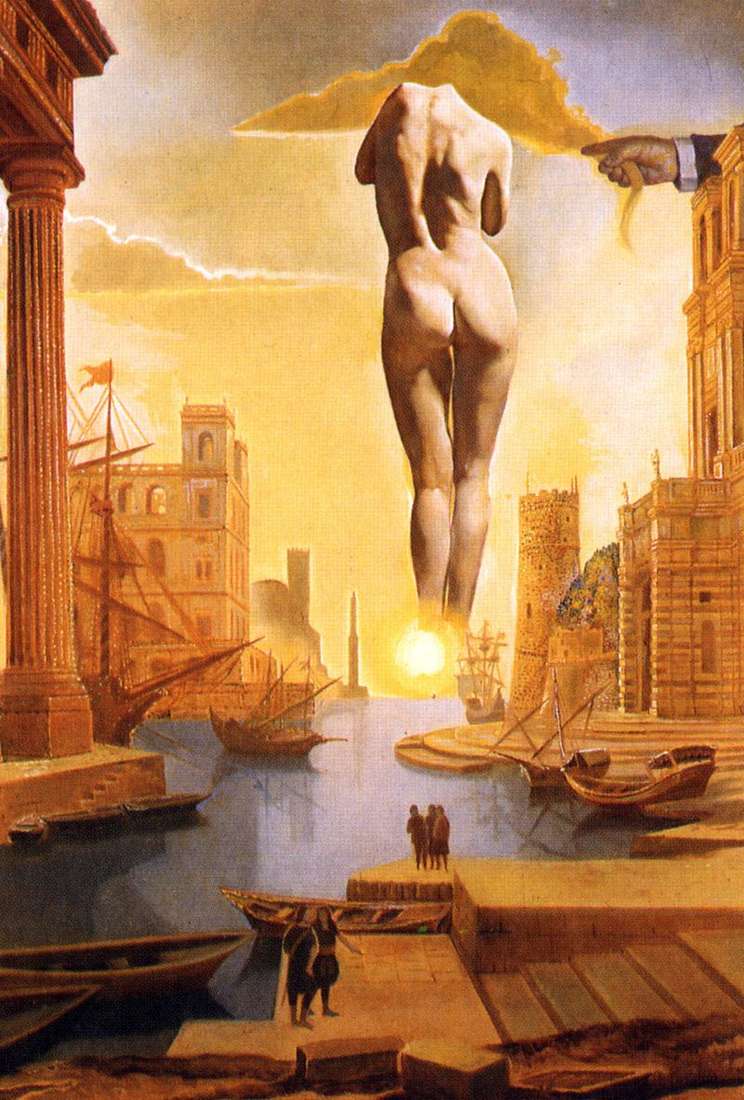

Sleep approaches by Salvador Dali Dali’s hand steals the golden fleece to show the Gala-Dawn by Salvador Dali

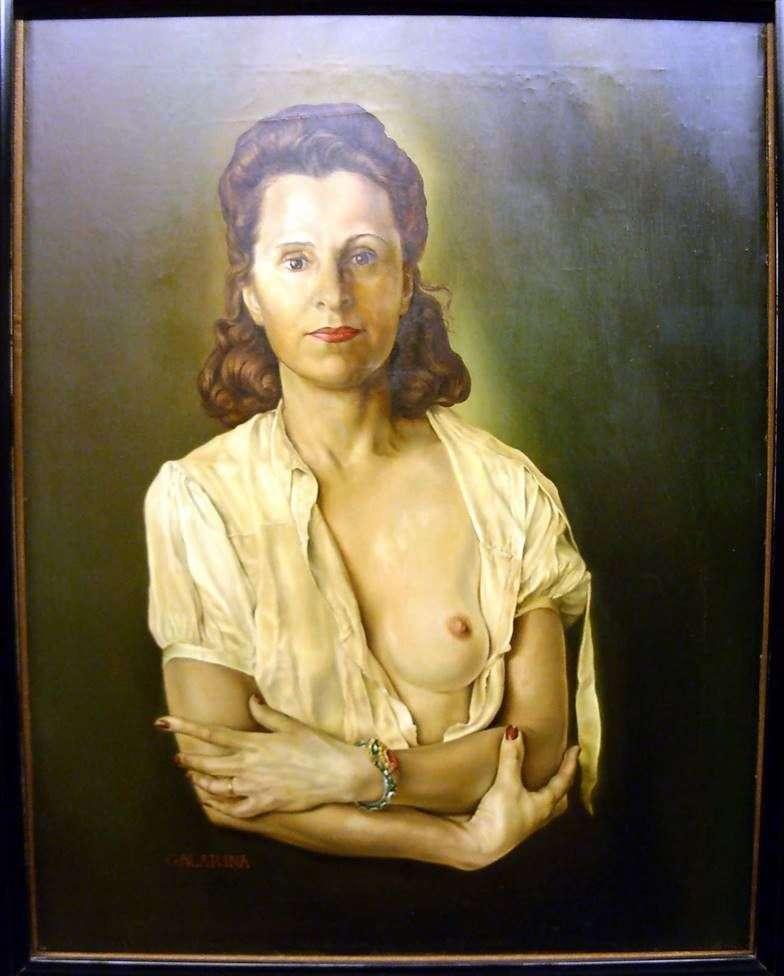

Dali’s hand steals the golden fleece to show the Gala-Dawn by Salvador Dali Galarina by Salvador Dali

Galarina by Salvador Dali