This picture is one of Bellini’s earliest masterpieces. The center of the composition is the figure of the kneeling Christ. Below the viewer sees three sleeping disciples of the Savior – Peter, James and John. They had to stay awake, but fell asleep. In the sky the dawn flares up, foreshadowing the end of a long night and the beginning of a new day-the day of the Lord’s crucifixion.

Against the background of clouds, the artist painted an angel holding a bowl. This cup of suffering, redeeming the sins of mankind, the Savior will have to drink to the bottom. On the way, a detachment of Roman soldiers, led by Judas, is already on his way to arrest Jesus.

The surrounding landscape corresponds to the details mentioned in the Bible and at the same time helps the artist to give the necessary emotional sound to the whole scene. The rising sun paints the edges of the clouds with pinkish highlights and floods the whole scene with golden light, which says that a hopeless night of spiritual blindness is behind us. There comes a new era of salvation and hope. Bellini was one of the first Italian artists of the Renaissance, who began using the landscape to reinforce the realistic sound of the picture. Winding, runaway paths trace the viewer’s view to the Italian city, spreading on top of the hill, the view of which allows the painter to emphasize the universality and timeless significance of the depicted event.

Carefully designed landscape helps Bellini to achieve the necessary lighting of the scene and, consequently, create the necessary mood. The landscape in the picture of Bellini is filled with the light of dawn. Tones here change from cold and transparent in the background to warm, golden in the foreground. It is believed that, working on the “Prayer for the Chalice,” Bellini was the first of Italian artists to paint the sunrise on the basis of direct observations of the atmosphere.

Art critic Paul Hills notes “the unusual plasticity of Bellini’s stone formations and hills.” He conducts a curious analogy between this landscape and the products of the Venetian glass-blowing masters of the fifteenth century. In particular, Hills recalls the so-called “chalcedony glass”, with which glass blowers mimicked various stones, and compares with it the soft, seemingly “swimming” forms of the Bellini landscape.

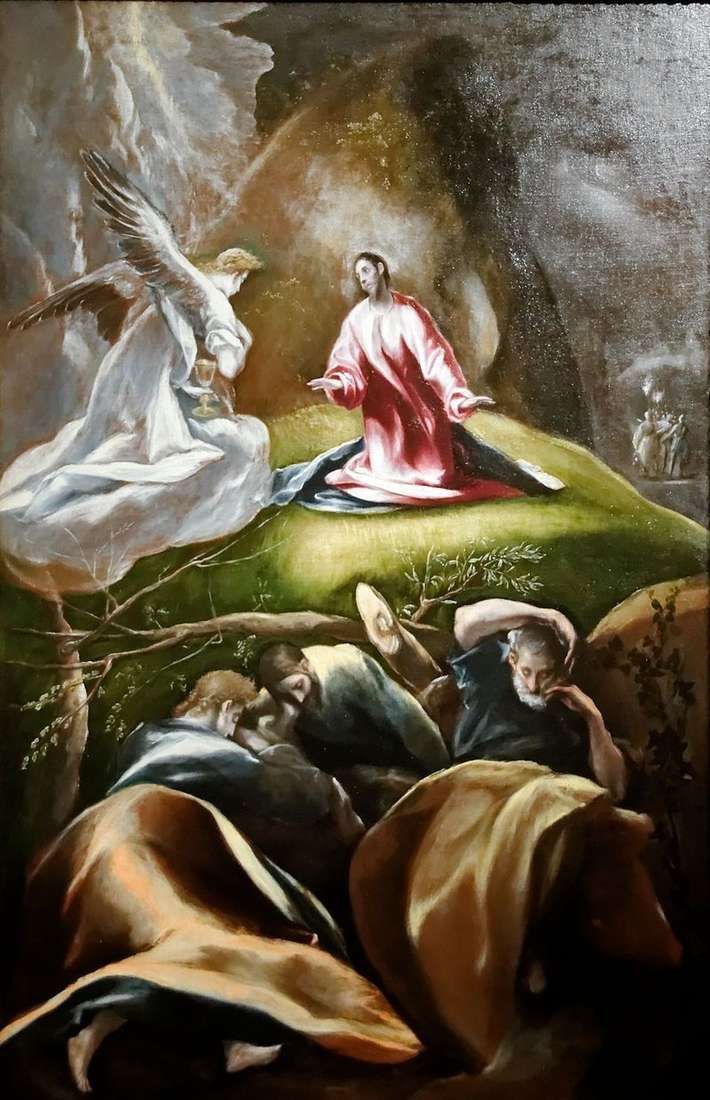

Passion in the Garden (Prayer for the Chalice) by El Greco

Passion in the Garden (Prayer for the Chalice) by El Greco Ecstasy of St. Francis by Giovanni Bellini

Ecstasy of St. Francis by Giovanni Bellini Portrait of a man by Giovanni Bellini

Portrait of a man by Giovanni Bellini Prayer in the Garden of Gethsemane by Correggio (Antonio Allegri)

Prayer in the Garden of Gethsemane by Correggio (Antonio Allegri) Madonna and baby with a blessing by Giovanni Bellini

Madonna and baby with a blessing by Giovanni Bellini Nude young woman with a mirror by Giovanni Bellini

Nude young woman with a mirror by Giovanni Bellini Portrait of Condottier Giovanni Emo by Giovanni Bellini

Portrait of Condottier Giovanni Emo by Giovanni Bellini St. George and the Dragon by Giovanni Bellini

St. George and the Dragon by Giovanni Bellini