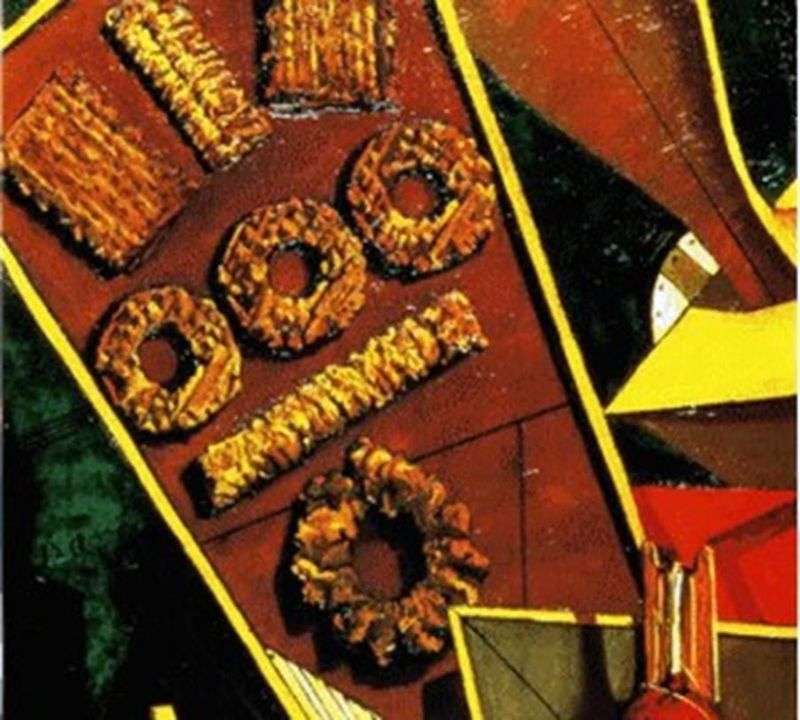

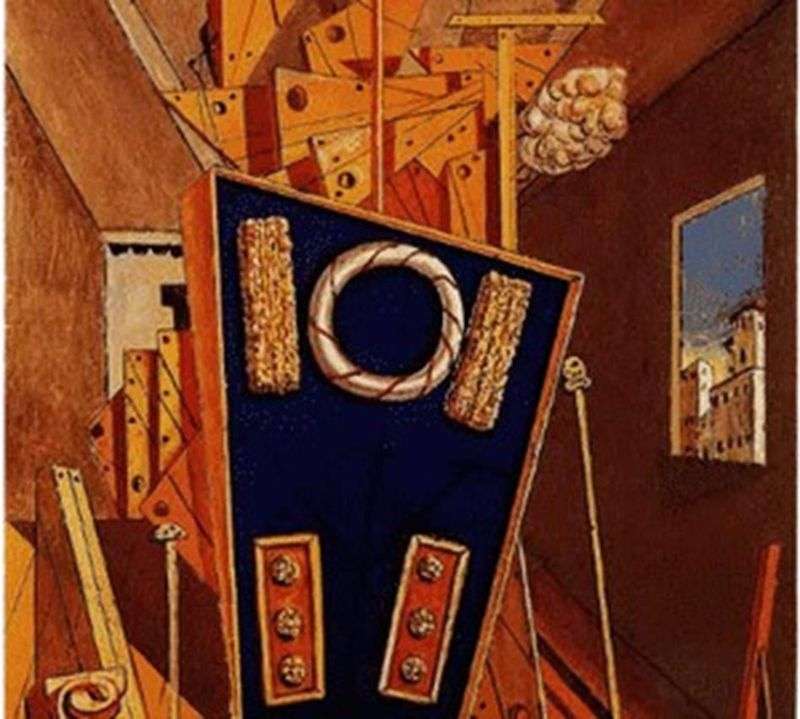

During the First World War, in 1917, de Chirico serves in a hospital in Villa del Seminario near Ferrara. There he also gets acquainted with artists, like him, drafted into the army. In those years, he creates six paintings that compiled the series “Metaphysical Interiors”, the second title of which is “The Discovery of a Lonely Man.” On the canvas is a heap of very naturalistically illustrated cookies and a variety of measuring instruments: angles, rulers, frames, connected in a very balanced composition. On the right is the head of a dummy, resembling a tennis racket.

In the foreground appears hyper-realistic colorful cork float. The master connects objects depicted in a realistic manner, with schematic, sketchy images. All this occurs in a very limited space, which allows the author to hypertrophy the prospective reduction. And this time the objects seem completely unrelated to each other. These are symbolic signs, assembled together to solve the metaphysical tasks of the author. The human presence is indicated by the barely recognizable head of the mannequin.

Any life disappears from painting. The space is completely closed, only a cookie lying on a flat surface creates a picture in the picture. Everything becomes a way of image, and there is a feeling of an inevitable separation from reality. What used to be a space has turned into a bunch of frames, angles and “pictures in pictures”. Weight turns into pure geometry – except for the float and the head of the dummy. Angular plans are superimposed on each other and on themselves.

A typical feature of these metaphysical paintings is the lack of logical connections between objects and strong prospective cuts. Having created several paintings in 1917 from a series of so-called metaphysical interiors, de Chirico abandons this theme and changes the direction of his creative search. However, in 1960, the artist returns to the old experiments with a set of objects, while opening the space.

Metaphysical interior with biscuits by Giorgio de Chirico

Metaphysical interior with biscuits by Giorgio de Chirico Purity of the imagination by Giorgio de Chirico

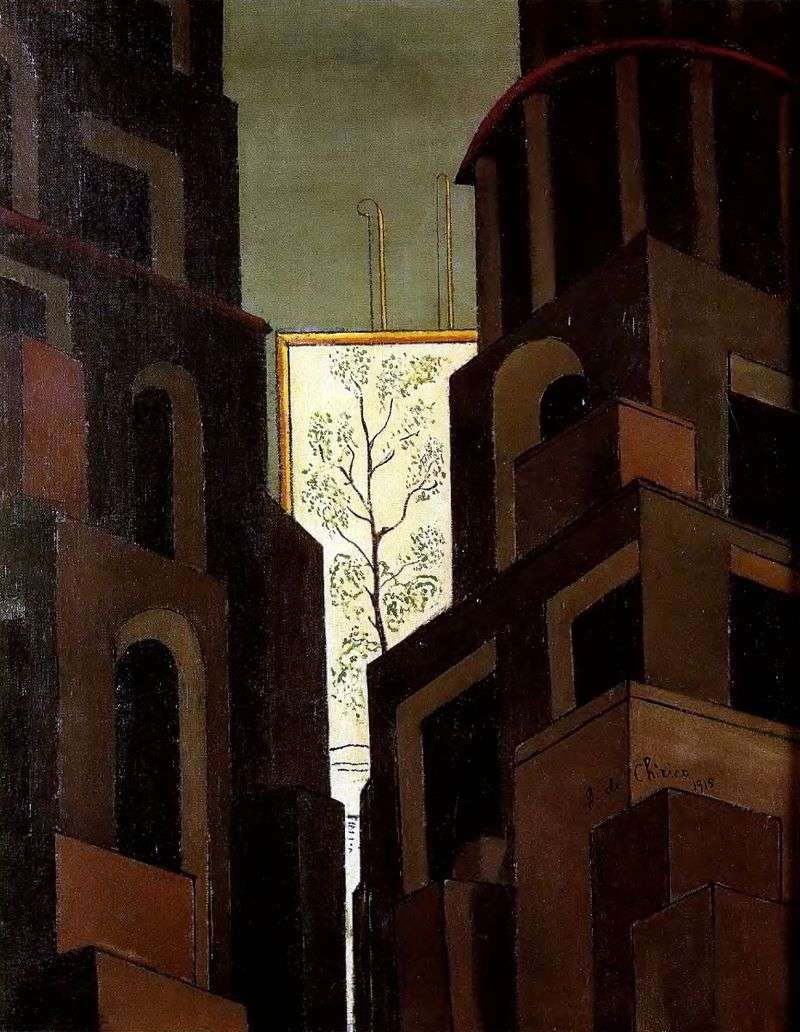

Purity of the imagination by Giorgio de Chirico Walk of the philosopher by Giorgio de Chirico

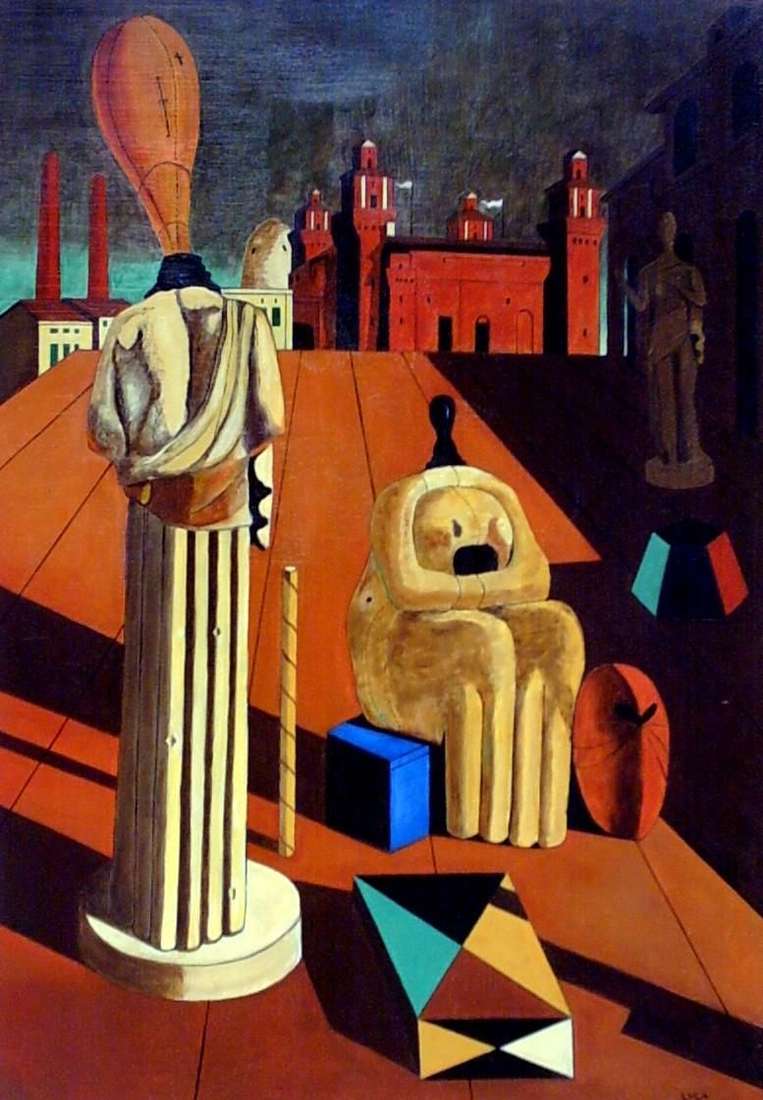

Walk of the philosopher by Giorgio de Chirico Destruction of the Muses by Giorgio de Chirico

Destruction of the Muses by Giorgio de Chirico The Prodigal Son by Giorgio de Chirico

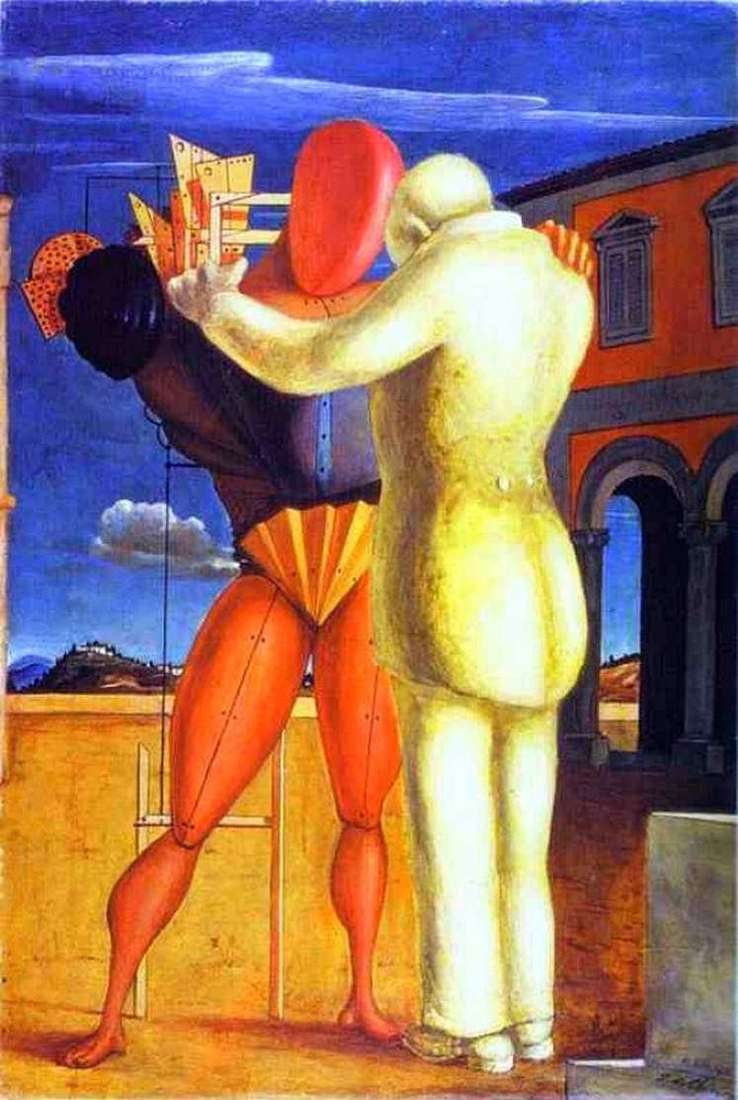

The Prodigal Son by Giorgio de Chirico Archaeological cycle by Giorgio de Chirico

Archaeological cycle by Giorgio de Chirico Classic figures in the room by Giorgio de Chirico

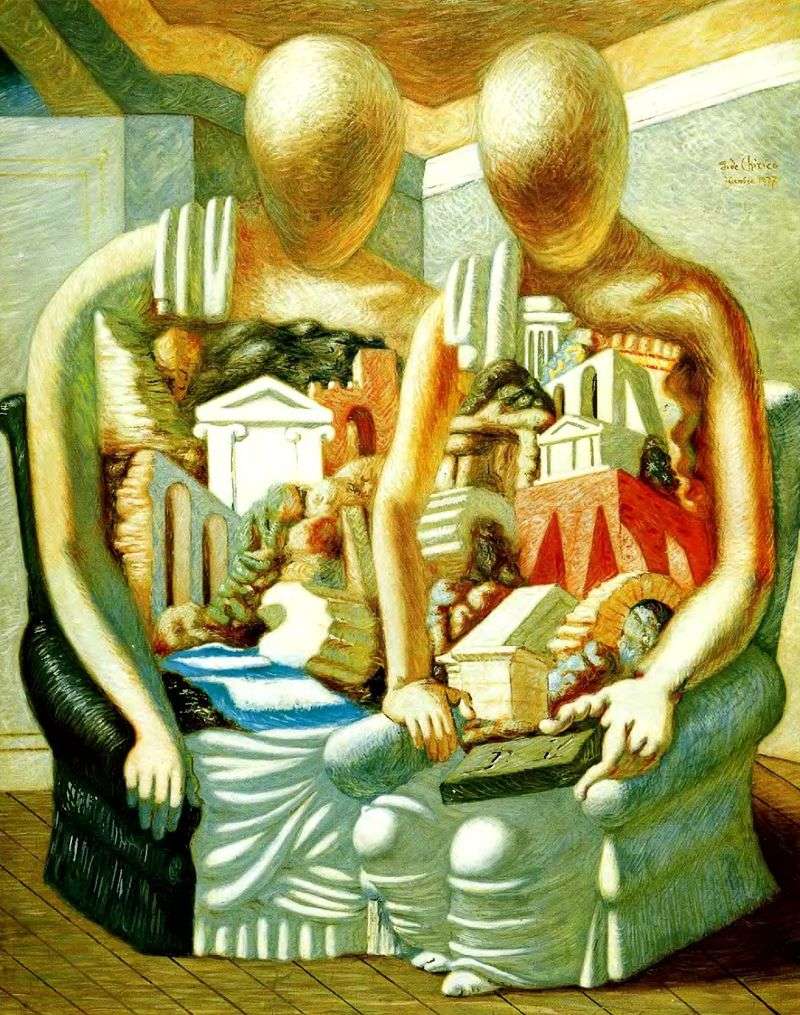

Classic figures in the room by Giorgio de Chirico Melancholy and the mystery of the street by Giorgio de Chirico

Melancholy and the mystery of the street by Giorgio de Chirico