Monet’s own work has now taken a new direction; this became apparent when, in 1891, he displayed a series of fifteen paintings by Durand-Ruel, depicting haystacks at various times of the day. According to him, he assumed at first that for the transfer of the object with different lighting, two canvases are enough – one for cloudy weather, the other for sunny. But, working on these haystacks, he discovered that the effects of light are constantly changing, and decided to keep all these impressions on a number of canvases, working on them in turn, each canvas was devoted to one particular effect. Thus, he tried to achieve what he called “instantaneousness” and argued that it is very important to stop working on one canvas as soon as the light changes, and to continue it over the next, “

His series “Stogov” was followed by similar series “Topol”, the facades of Rouen Cathedral, views of London and water lilies growing in the pond of his garden in Giverny. In the pursuit of methodically, almost with scientific accuracy to observe the continuous changes of light, Monet lost the immediacy of perception. Now he was disgusted with “light things that are created in unison”, but it was in these “light things” that his gift to grasp the radiant magnificence of nature in his first impression.

The stubbornness with which he was now competing with the light, was contrary to his experience and talent. While his paintings often provide a brilliant solution to this problem, the problem itself remained a pure experiment and imposed strict limitations.

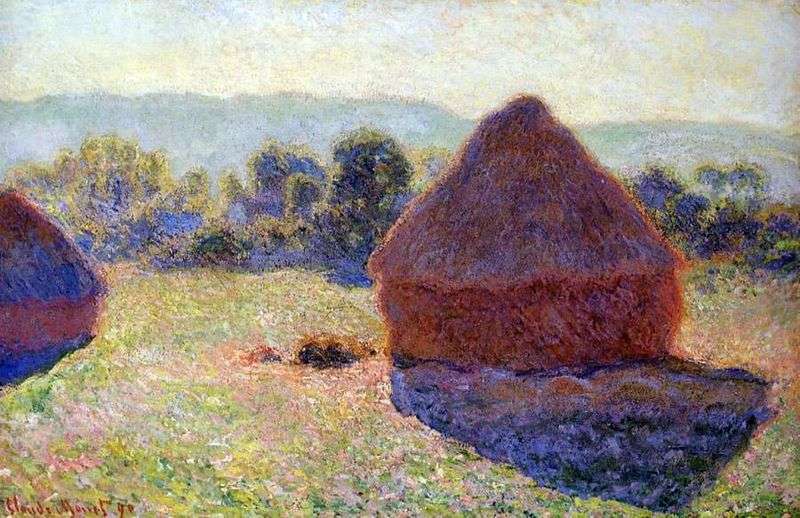

Haystack by Claude Monet

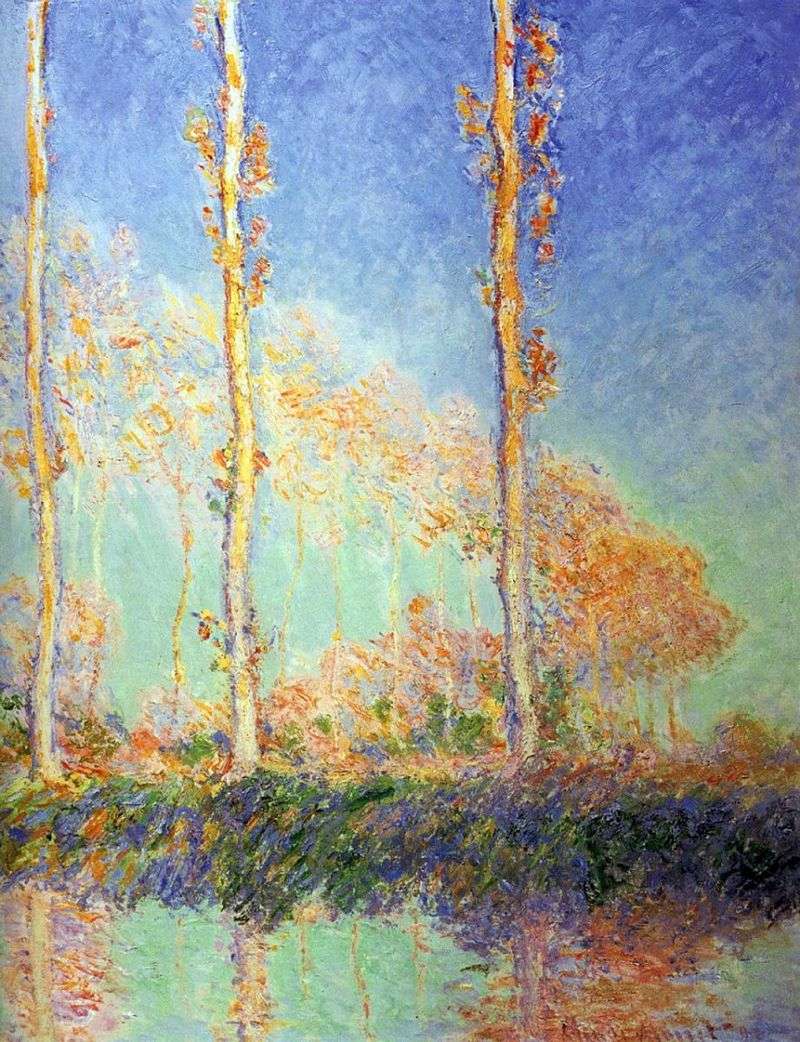

Haystack by Claude Monet Poplars, Three Pink Trees in Autumn by Claude Monet

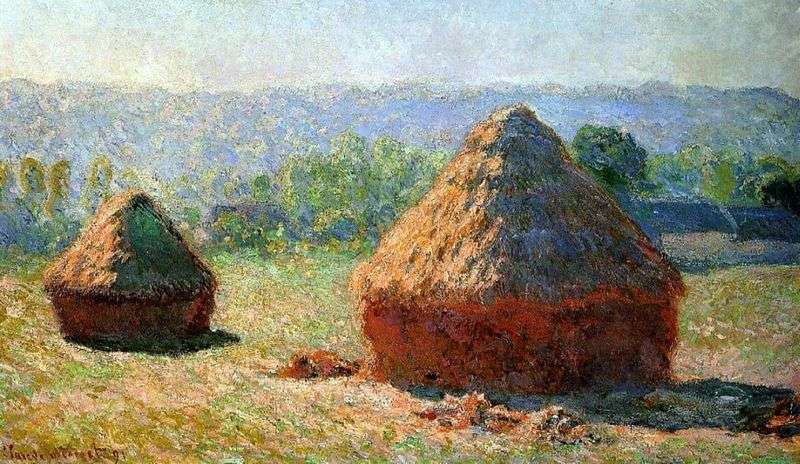

Poplars, Three Pink Trees in Autumn by Claude Monet Haystacks by Claude Monet

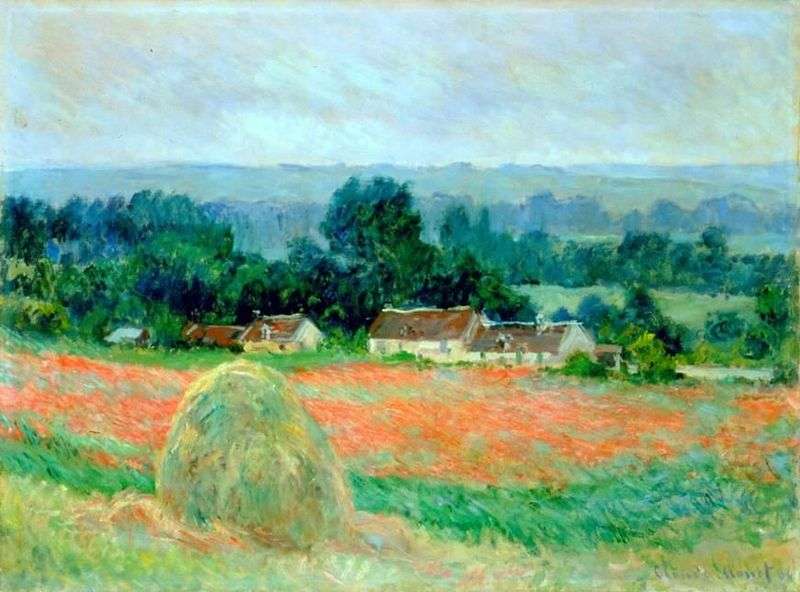

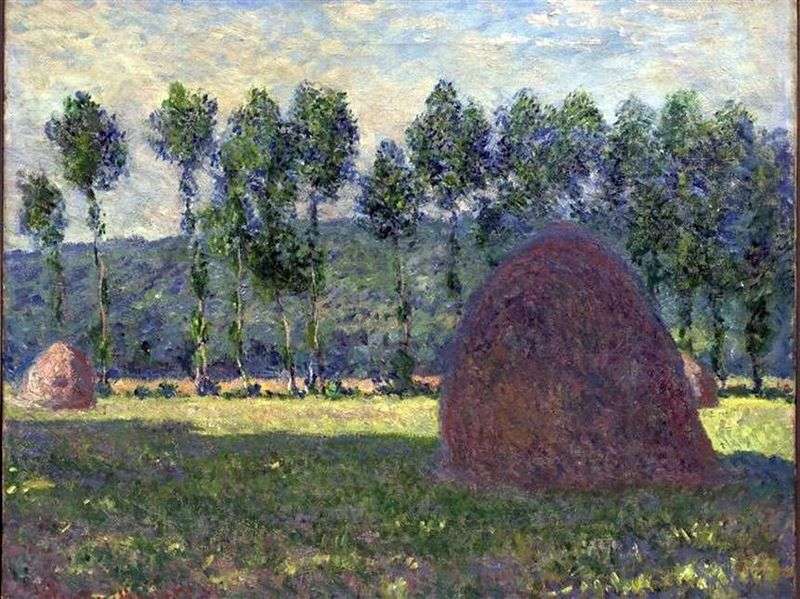

Haystacks by Claude Monet Haystack at Giverny by Claude Monet

Haystack at Giverny by Claude Monet Haystack by Claude Monet

Haystack by Claude Monet Boulevard Montmartre. Afternoon, sunny by Camille Pissarro

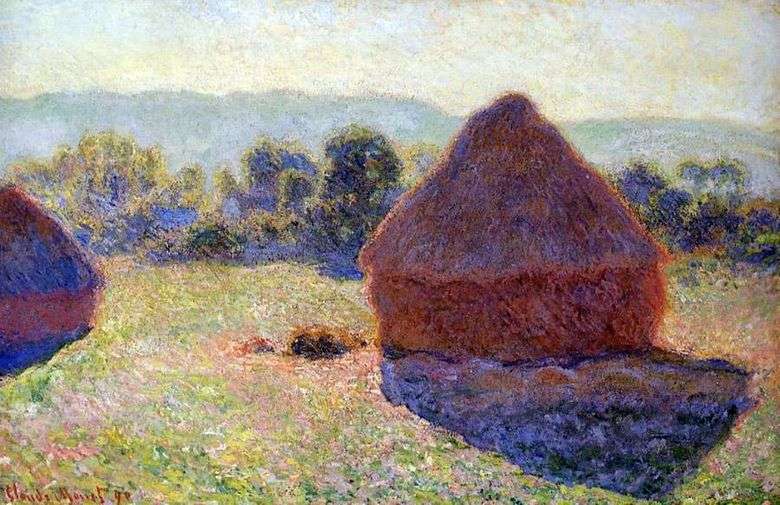

Boulevard Montmartre. Afternoon, sunny by Camille Pissarro Haystack en una tarde soleada – Claude Monet

Haystack en una tarde soleada – Claude Monet Rouen Cathedral by Claude Monet

Rouen Cathedral by Claude Monet