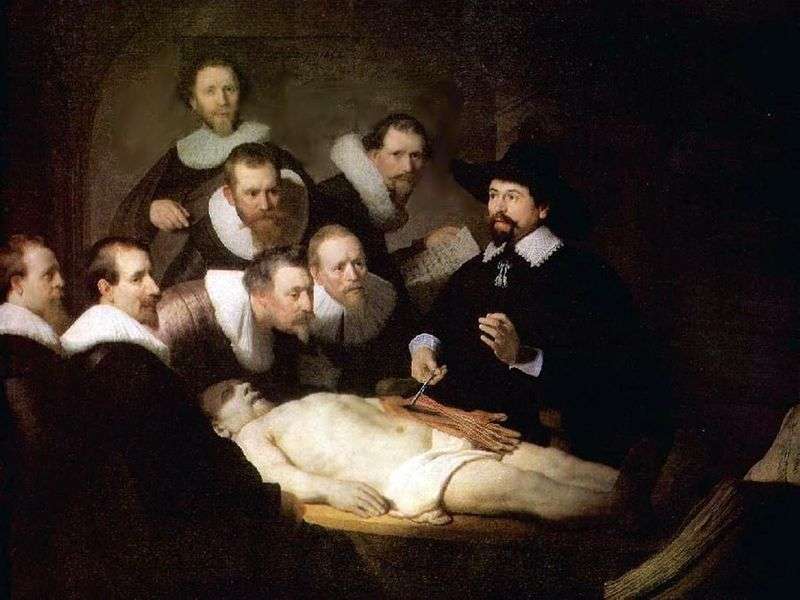

The painting “The Lesson of Anatomy of Dr. Tulpa”, in which the artist innovatively solved the problem of a group portrait, giving the composition life’s ease and uniting the portraits by a single action, brought Rembrandt wide popularity. The group portrait genre was widely spread in the 17th century Holland. For the first time in history, having felt themselves as the masters of life, traders and artisans sought to become heroes of art. The painters of that time left numerous images to posterity. Burghers are portrayed separately, with their wives, with children, and, finally, with entire corporations.

These professional corporations, the so-called guilds, born of the medieval era and during the period of the Dutch revolution, often played the role of militant organizations, were not yet destroyed by the development of capitalist production and rather successfully continued to exist in Dutch cities of the 17th century. The image of the guild members becomes the main theme of the Dutch group portrait.

In the portrait of doctors, the young artist continues his search for plot action. On a large canvas, the viewer sees a group of people listening to a lecture on anatomy. Opening the hand of the deceased, the professor pulls down with tweezers and demonstrates to his listeners the muscle that controls the movement of the fingers. With the fingers of his left hand, he shows how this muscle acts. In the right corner of the picture is an anatomical atlas, opened on the desired page.

The picture is solved in a mean black and white. A stream of light pours into a dim audience, snatching people’s faces from the darkness and the dead body, around which they were crowded. The artist seeks to convey the different reactions of the stage participants to what they see and hear at the moment. Sitting next to Tulpa turned his face towards the speaker, as if watching the movement of the fingers of his left hand. The other, bent low over the corpse, as if peering into a table of anatomically opened atlas. Standing behind him with lively attention watching Tulpa demonstration, all leaning forward.

In an effort to create the illusion of the full reality of what is happening, the artist makes the event the participant himself. The spectator as if enters the audience during the lecture, and the eyes of two Tulpa students turn to him.

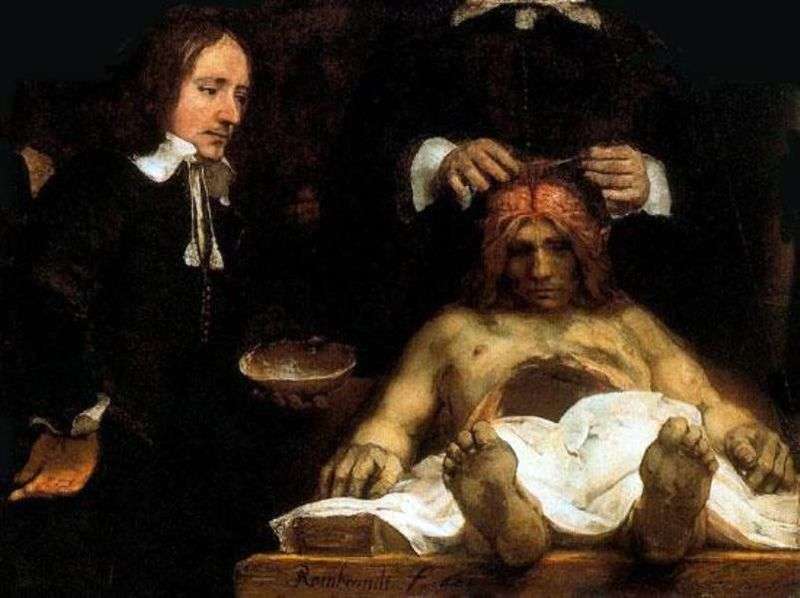

Dr. Deiman’s Anatomy Lesson by Rembrandt Harmens Van Rhine

Dr. Deiman’s Anatomy Lesson by Rembrandt Harmens Van Rhine Portrait of Maria Trip by Rembrandt Harmens Van Rhine

Portrait of Maria Trip by Rembrandt Harmens Van Rhine Frederick Riel on horseback by Rembrandt Harmens Van Rhine

Frederick Riel on horseback by Rembrandt Harmens Van Rhine Shuttle of Christ in a Storm by Rembrandt Harmens Van Rhine

Shuttle of Christ in a Storm by Rembrandt Harmens Van Rhine Lección de anatomía del Dr. Nicholas Tulp – Rembrandt Harmens Van Rhine

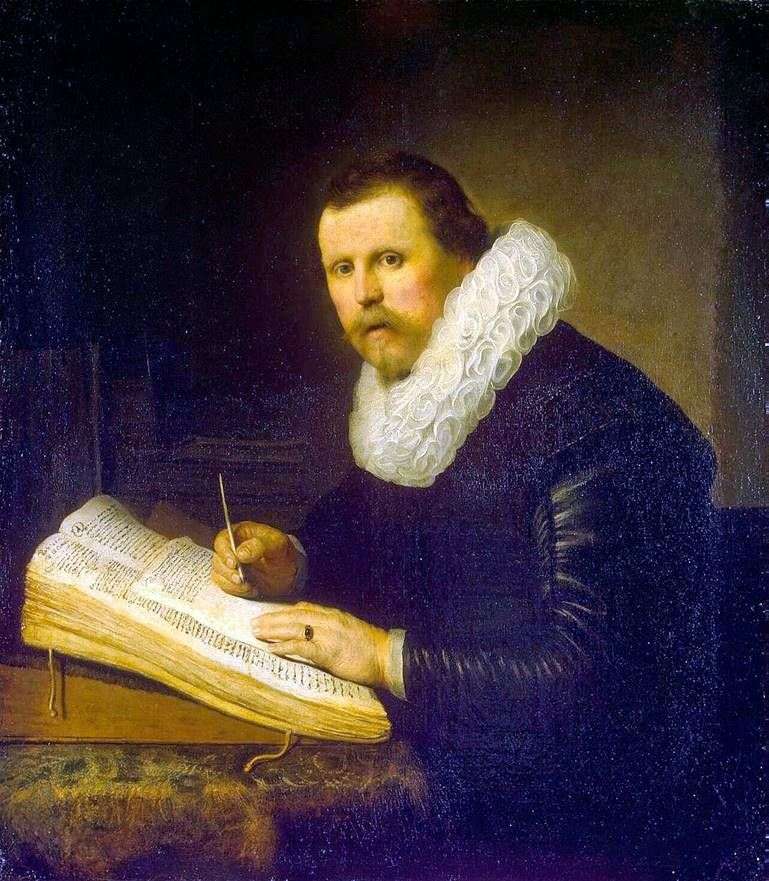

Lección de anatomía del Dr. Nicholas Tulp – Rembrandt Harmens Van Rhine Portrait of Jan Utenbogarta by Rembrandt Harmens Van Rhine

Portrait of Jan Utenbogarta by Rembrandt Harmens Van Rhine Self Portrait at the Age of 34 by Rembrandt Harmens Van Rhine

Self Portrait at the Age of 34 by Rembrandt Harmens Van Rhine Portrait of a Scientist by Rembrandt Harmens Van Rhine

Portrait of a Scientist by Rembrandt Harmens Van Rhine