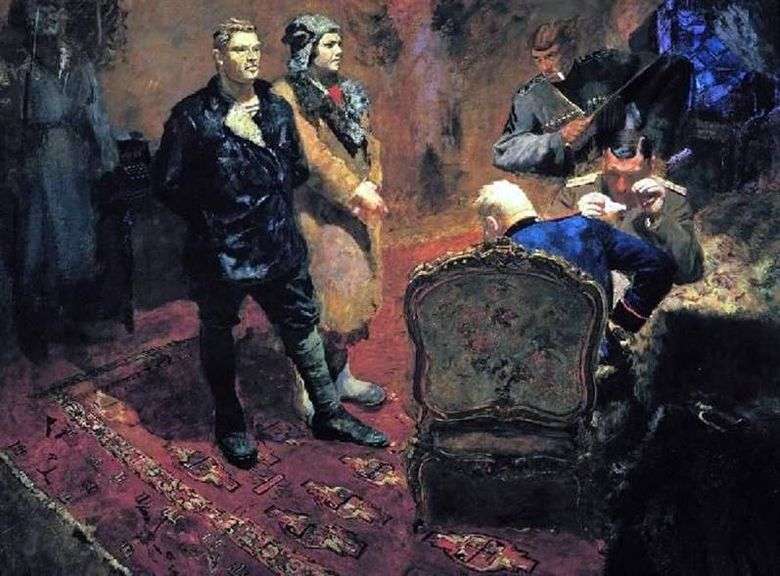

The composition of the painting “At the Old Ural Plant” belongs to the number of the most profound artistic decisions in Soviet pictorial art. Its merit is, first of all, its clarity and accuracy.

Like in the “Interrogation of the Communists,” Johanson here subtly uses the silhouette-decorative side of the composition structure. In the composition of the picture three characters’ plans: the first, the near, – the master and the sitting worker; the second is a clerk, an old worker, and a stoker bending over the stove; the third is a teenage boy and two bent figures of workers whose faces are not visible.

The relationship of all the actors found by the artist allows you to immediately grasp the entire group of their eyes. However, almost simultaneously with the fixation of the whole composition-plastic structure of the picture, the eye immediately identifies the figures of the worker and the master; they most of all take possession of his attention. Focusing on them, the viewer comprehends the essence of what is happening. Without going into the analysis of everything that is depicted in the picture, we see that these central heroes are irreconcilable enemies and that a struggle is going on between them. The eye runs from one figure to another; captured by the duel of these people, we, as it were, become participants in the events.

Peering into the picture, you see that the moral superiority on the side of the worker. Although he is sitting on the floor, his figure is so internally so active that it is clear – just about he will rise and straighten up to his full height, will appear a giant. The manufacturer is standing, but his figure is not firm; he seemed to be swayed and forced to do the reverse movement, lean on the cane.

This, devoid of all affectation, the opposition of the two struggling classes was carried out by Johanson with genuine artistic skill. The painter was following the truthful reflection of the historical conditions of the beginning of the great social struggle. The worker who has entered into a struggle with his exploiter is still in the servile position of a hired slave. The capitalist breeder is still the lord of the labor of the workers, the master of the situation.

In the right side of the picture is a group of plant workers. It seems at first glance somewhat disjointed and yet plastically generalized. The old worker and the fireman seem to protect their comrade, the seated worker. Pink-dark, bronze-brown reflections on their figures emphasize the harsh appearance of the proletarians tortured with hard labor. A tall old man with an iron rod in his hand stood up and was about to speak, too, and would move to the master. And even the old fireman, apparently, hears the words of the protesting comrade. Perhaps, soon he will, without fear, rush into the oppressor. A frail, consumptive boy standing from behind, and he also all somehow reached forward. And it is no coincidence that Johanson lights up a group of second-rate workers like a raging flame.

The picture of Johanson reflects that period in the history of the revolutionary movement, when workers turn from requests to demands. Through the images of simple workers-proletarians, the artist showed how terrible this collective protest of the masses against the exploiters would be, what devastating anger they would respond to the dissatisfaction of their demands. These masses will eventually unite and will move to storm the strongholds of capitalism.

Analysis of the composition of the picture allows us to conclude that life’s credibility is combined in it with clear stage expressiveness. Johanson here in full force unfolded artistic direction, without which it is impossible to create a genre work.

Great importance for the emotional effectiveness of the picture of Johanson has the expression of the eye of her heroes. The eyes are the mirror of the soul, they convey the spiritual life of man. The struggle of views helps the artist to reveal the essence of the relationship between the workers and the master more deeply, and also to understand the collective psychology of the working masses.

The flashing eyes of the old worker, the stoker and the boy are sharp, piercing, white, flashing to one point, full of a single feeling, and what a strong pressure of accumulated anger to the oppressors they express, how they “destroy” those eyes of the hated owner-breeder. Already one by one the “duel of the eyes” of the workers and the master sees the spectator, whose inevitable victory ends this struggle.

The central figure of the worker is depicted by the artist at the gully. On a working pink shirt with a wide open collar, a gray apron, bast shoes on his feet. The face of the worker wears traces of heavy, debilitating deprivations, sharp eyes are inflamed, but his hands, smeared with coal, are full of great muscular strength. It is a radical proletarian who has come to the realization that he and his comrades have nothing to lose but their chains.

The light of consciousness spiritualizes the face of the proletarian worker who has risen to open protest. And here, as in the “Interrogation of the Communists,” Johanson makes extensive use of the introduction into the artistic system of a picture of revolutionary romance. Here is the romance of a great idea, the romanticism of foreseeing the bright future of the working class.

Johanson puts all the passion of the painter into the image of the worker-caster. The artist paints the features of his face boldly, admires the depth of his eyes, the physical strength of his hands, shoulders, the energy of his spirit. The shirt and apron of the worker, soiled with earth and soot, remaining themselves in their material concreteness, acquire, under the brush of Johanson, that particular beauty of color that even more elevates and makes the whole figure of the caster noble. In these parts of the picture Johanson richly uses the texture of the letter, here and there leaves the canvas free, revealing a granular surface.

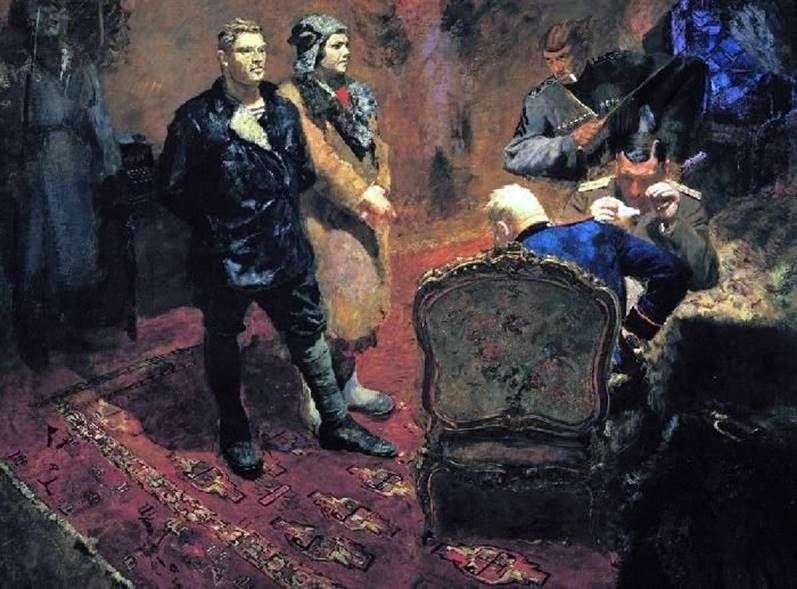

Interrogation of Communists by Boris Ioganson

Interrogation of Communists by Boris Ioganson En la antigua fábrica de los Urales – Boris Ioganson

En la antigua fábrica de los Urales – Boris Ioganson Bolshevik by Boris Kustodiev

Bolshevik by Boris Kustodiev The formula of the Petrograd proletariat by Pavel Filonov

The formula of the Petrograd proletariat by Pavel Filonov El interrogatorio comunista – Boris Ioganson

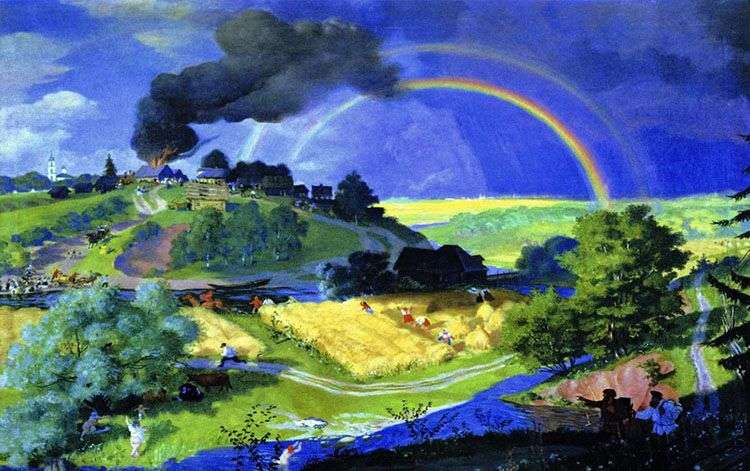

El interrogatorio comunista – Boris Ioganson After the storm by Boris Kustodiev

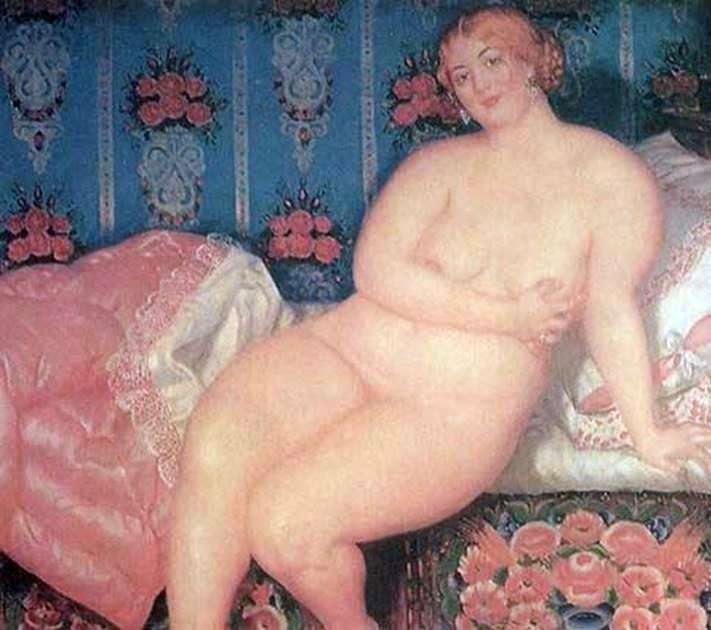

After the storm by Boris Kustodiev Beauty by Boris Kustodiev

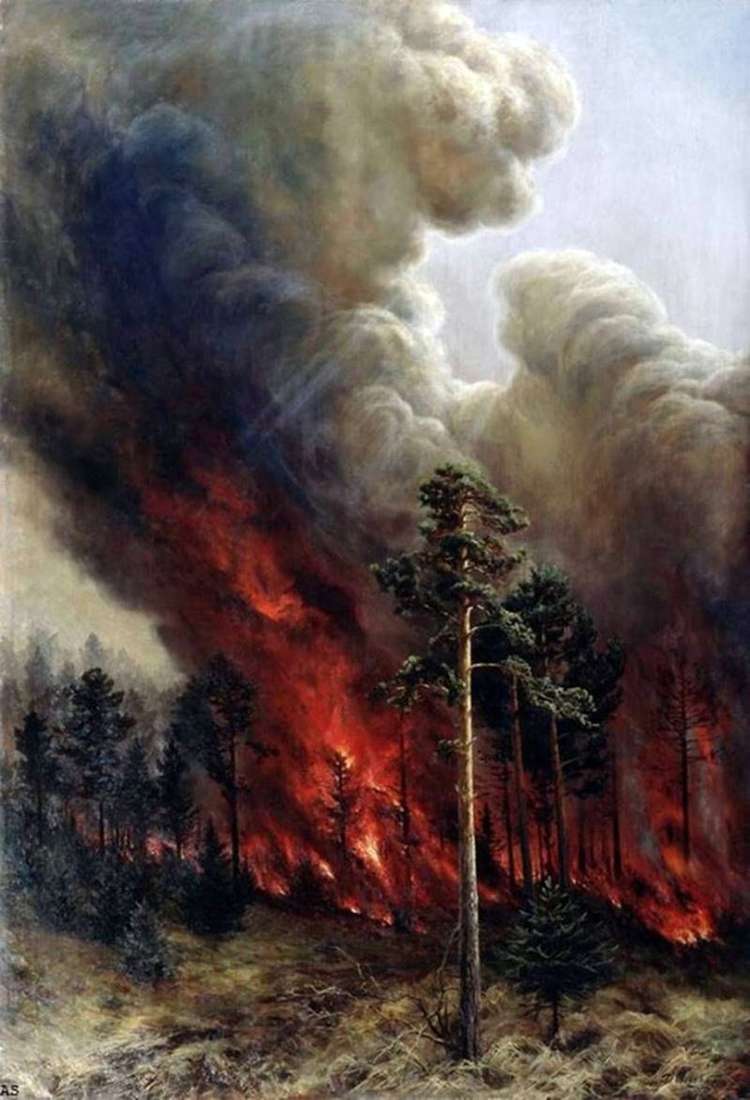

Beauty by Boris Kustodiev Forest fire by Alexey Denisov-Ural

Forest fire by Alexey Denisov-Ural