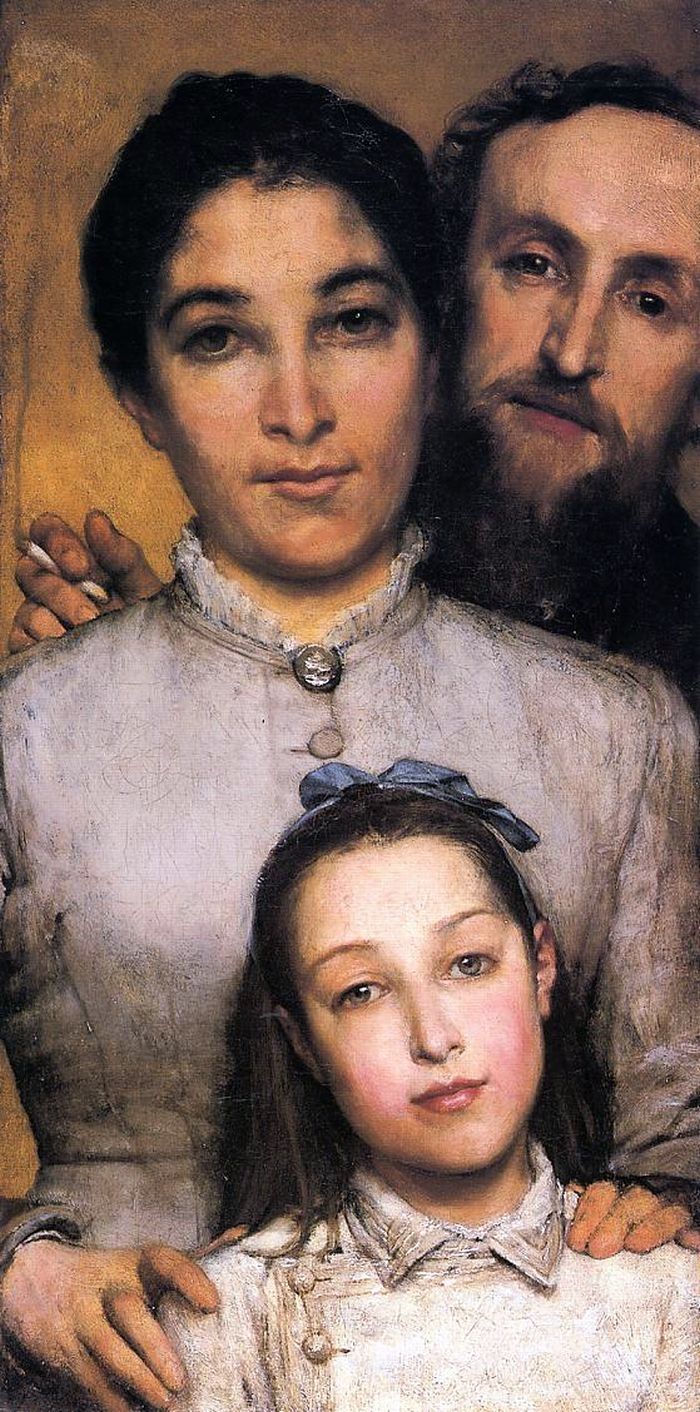

Aime Jules Dalu, his wife and daughter The portrait of the Dalu family was written by the British painter Alma-Tadema Lawrence in 1876 during the prosperity of the Victorian era, when the foundations of the society’s morals were diligence, economy, punctuality and sobriety. These postulates influenced, among other things, the development of art and painting, in particular. The presented family trip to Dalia is a striking example of this, modest, frankly – realistic, mean to exaggerations.

The work is dedicated to the equally famous sculptor E. Zh. Dal, whose hand belongs to the works of “Eugene Delacroix’s Memory”, “Triumph of Silena” in the Luxembourg Garden, and the tomb of V. Noir in the Pere Lachaise cemetery. It should be noted that the artist himself did not consider himself a portraitist, giving preference to historical subjects. As for writing portraits, his attention was given only to close people and friends. Family Dahl, apparently, was friendly with the author. Her portrait turned out to be simple and like a quick letter from nature, by accident.

Very bright work, is not it? The sculptor’s daughter is young and bleached with light to cleanliness. She is like a bright spot in the life of her father – with a frank look, even without cunning and lies. The contrast of childishness of the child is emphasized by the fatigue of the mother and already by other eyes, full of anguish, vital wisdom, depth. Jules himself, like a glued image, hailed by the painter to turn around. He could hardly fit within the canvas. Its image is slightly erased due to the muted palette of the distant plan. However, the piercing gaze of the black eyes enlivens the face.

In talented fingers Dahl is caught burning cigarette. Everything speaks of the fleetingness of creating a work without a special production. In spite of Alma-Tadema’s assertion of non-participation in portraiture, the image of the four Dahl disproves this idea. The portrait is written very professionally, with an interesting bold layout of the characters, in a different, but inherent in that era, technique and with a different composition.

Aimé Jules Dalu, sa femme et sa fille – Lawrence Alma-Tadema

Aimé Jules Dalu, sa femme et sa fille – Lawrence Alma-Tadema Aime Jules Dahl, su esposa e hija – Lawrence Alma-Tadema

Aime Jules Dahl, su esposa e hija – Lawrence Alma-Tadema Not at Home by Laurence Alma-Tadema

Not at Home by Laurence Alma-Tadema Finding Moses by Lawrence Alma-Tadema

Finding Moses by Lawrence Alma-Tadema Self-portrait in his youth by Lawrence Alma-Tadema

Self-portrait in his youth by Lawrence Alma-Tadema Gallo-Roman women by Lawrence Alma-Tadema

Gallo-Roman women by Lawrence Alma-Tadema Favorable position by Lawrence Alma-tadema

Favorable position by Lawrence Alma-tadema Favorite poet by Lawrence Alma-Tadema

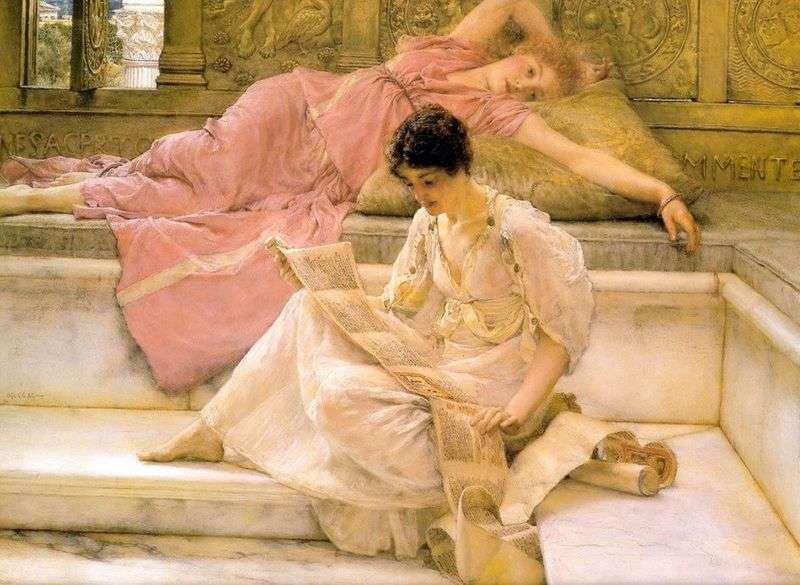

Favorite poet by Lawrence Alma-Tadema