In the same summer of 1889, Lautrec spent several weeks in Malmö, where he met his father and cousin Gabriel Tapier de Suleiran, who entered the University of Lille at the Medical Faculty. Tapie was twenty years old. He was a thin, tall young man with sloping shoulders, stooped, very pimply, with curly sideburns in Austrian fashion, with black shiny pomaded hair, separated by a straight cut to the back of his neck and combed over his temples.

Tapier had a special passion for precious baubles. On his thin and long fingers there were massive rings, on his stomach hung a thick gold chain from his pocket watch, on his pimply nose a golden pince-nez, from his pocket he casually removed a bulky silver cigarette-case with a family crest and extracted cigarettes from it. He tied a pin with a stone in his tie, and if anyone was interested in this stone, Tapier, with his characteristic pedantry, slowly explained in his soft voice that it was not chrysoprase and not agate, but simply “a piece of seven-meter sea shell”, and kindly informed its interlocutor her Latin name.

Lautrec enslaved his cousin Gabriel. He despotically forced him to fulfill all his whims, did not give him any initiative. It was worth the “doctor” to try and express his opinion, as Lautrec immediately broke off: “Charlotte, this is not your business.” Soon, Tapier came to Paris to continue his studies in medicine. Now Lautrec went everywhere with his cousin. Young people met every evening. They were a striking contrast, which, of course, amused Lautrec.

The lanky figure of the “doctor” emphasized the small growth of Lautrec, his ugliness, which he himself deliberately flaunted, or rather reinforced with his unusual costumes, grimaces, endless cartoons of himself. The one who saw this pair once saw a tall, stooping medical student, bending his head, following a dwarf stepping up to his chest, he would never forget this touching and sad picture. Tapier dearly loved Lautrec and felt sorry for him, although he did not show it to me. He endured endlessly with patience from his cousin everything, like the big dog that the child is torturing. A peaceful and kind young man with a gentle character, he forgave everything to his cousin, indulged all his whims and fulfilled any of his demands the more willingly that he believed in his talent and sincerely bowed before him.

Lautrec, who persistently sought to live the way a healthy person lives, never imagined that the reason for his condescending attitude towards him was not admiration for his talent – although he had already achieved it – but the compassion he evoked in people.

“Everything that he was able to achieve, he attributed to his will.” Childish trait. But there were a lot of children in Lautrec. In his twenty-seven years he was capricious, impatient and quick-tempered, although very forgiving. If he was not quickly agreed with him, he could start stomping his feet. He tried to make amusement out of everything. And was not his whole life a tragic and deadly game in which he played? Like every child, he often lost his sense of proportion. Tapier was a scapegoat for him.

It was forbidden to talk about politics, which Tapie loved so much and hated Lautrec. It was forbidden to take part in the discussion of art questions: “Do not interfere, this is not your business.” It was forbidden to greet people who were not favored by Lautrec, and even with the person whose face he simply did not like. Lautrec immediately pulled back his cousin. “Without-gift-nost!” he shouted to him, emphasizing every syllable. Tapier fell silent, lowered his head, but never got angry. It seemed even that he liked it, enjoyed such treatment.

And Lautrec no longer imagined life without his “doctor.” His society was indispensable for Lautrec.

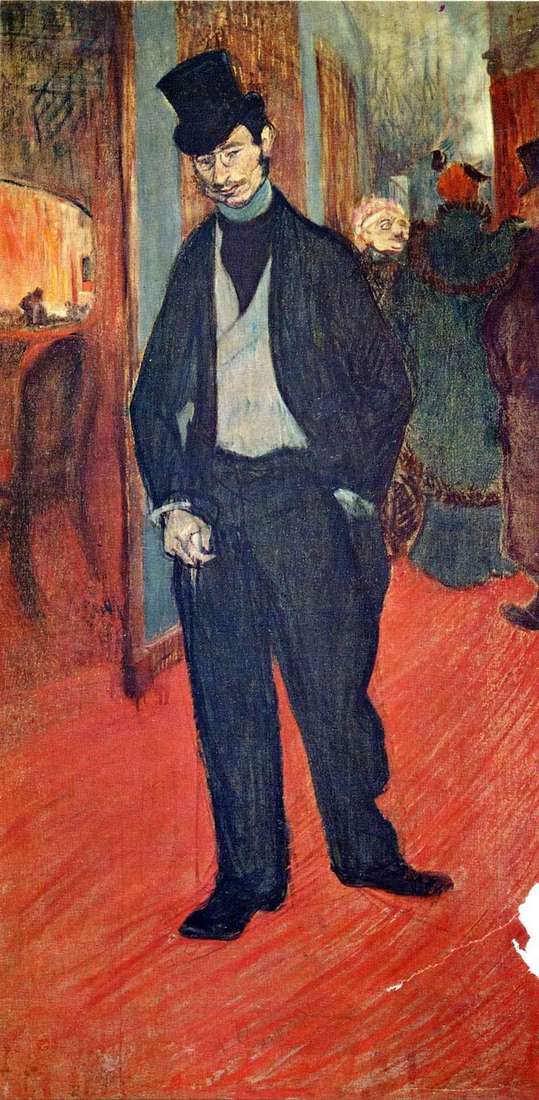

Tapier de Seleiran – Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

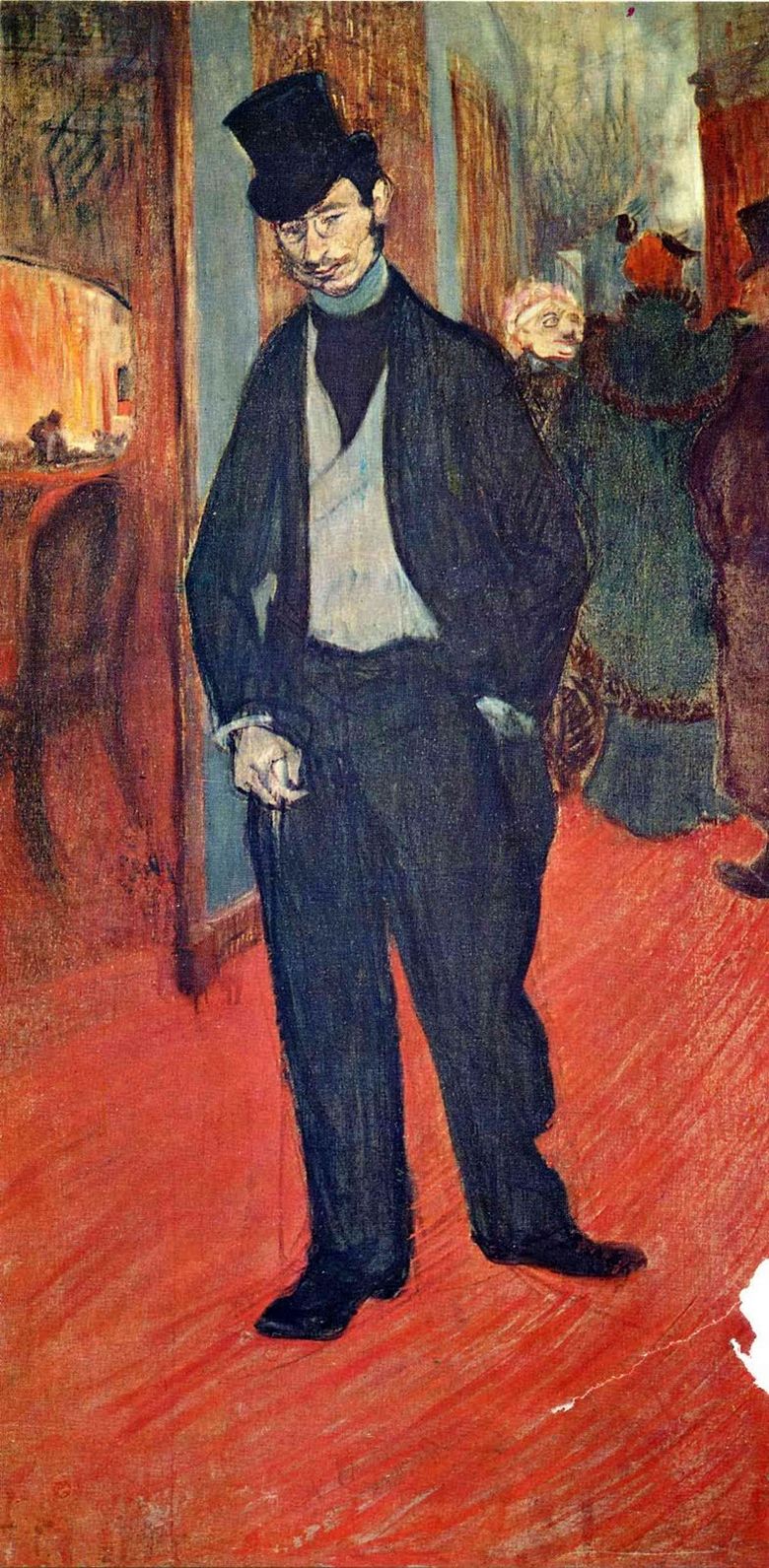

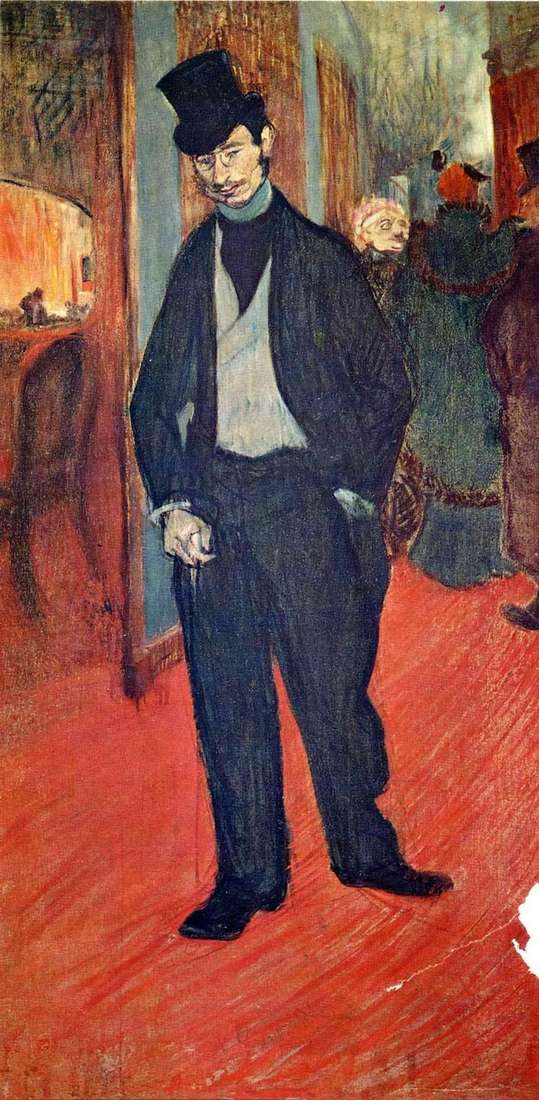

Tapier de Seleiran – Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec Tapier de Celerand – Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

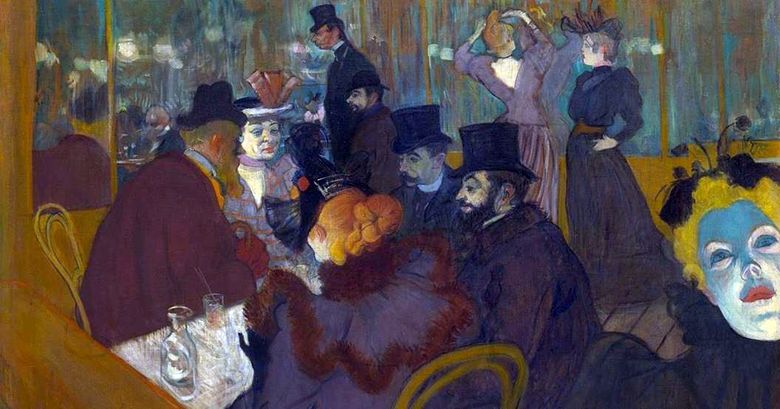

Tapier de Celerand – Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec In “Moulin Rouge” by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

In “Moulin Rouge” by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec Au Moulin Rouge – Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

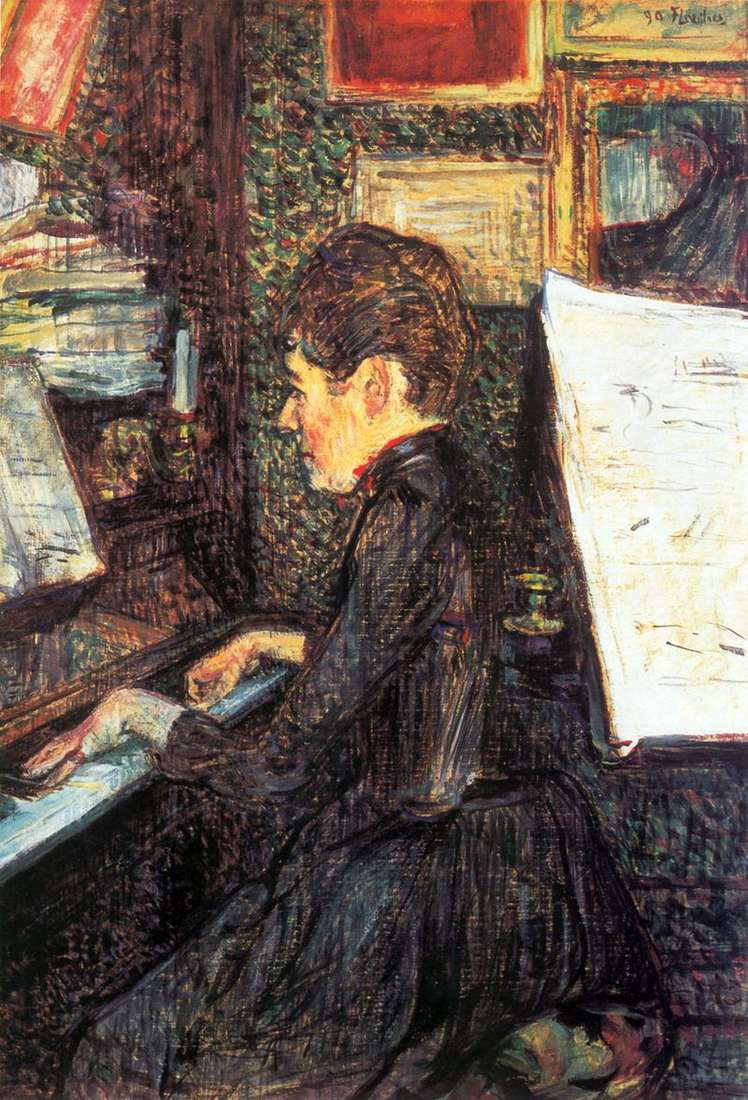

Au Moulin Rouge – Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec Mademoiselle Dio for the piano by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Mademoiselle Dio for the piano by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec Portrait of Louis Pascal by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

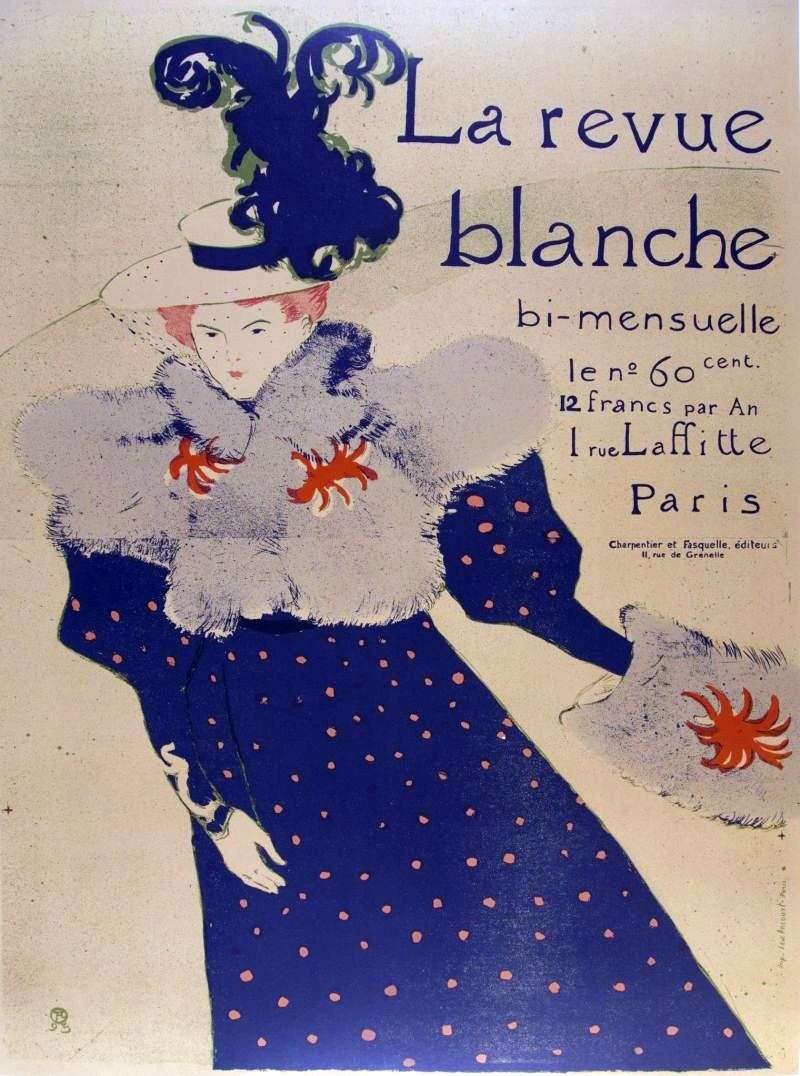

Portrait of Louis Pascal by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec Revue Blanche by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

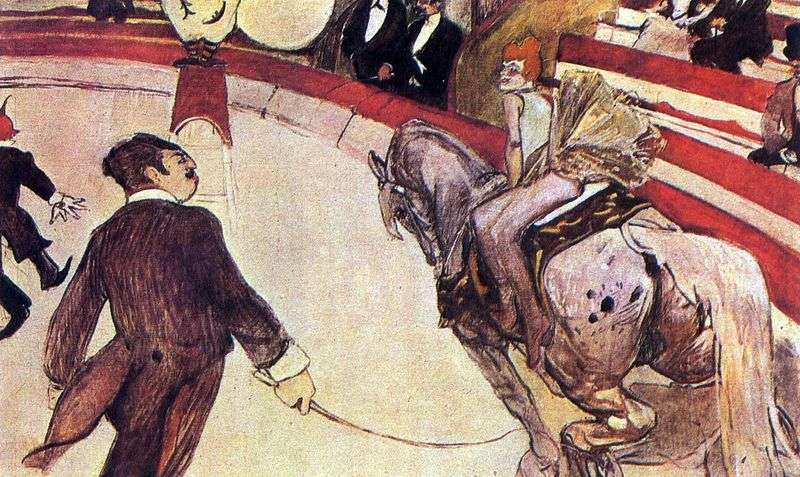

Revue Blanche by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec In the circus of Fernando by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

In the circus of Fernando by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec