The dark, sorrow-filled canvas of Vincent van Gogh in 1886 is a self-portrait, one of many, but perhaps the most real of all. This is a revelation in oil, written before the full-scale manifestations of madness and the cut off earlobe by the artist, before putting him in a psychiatric hospital.

The work breaks out of the post-pre-conscription current and rejects impressionism, with its bright colors and moments of joy. Look at yourself, how many dark paints and soot in oil. Grief and sadness about unsuccessful love and loneliness shines in every stroke with a brush.

Self-portrait, like an auto-print, deep and gray in content, embodies the artist’s whole life, from the very childhood, full of punishments and misunderstandings, to a mature life with his unappreciated love. Vincent van Gogh was not a portraitist. In connection with incomplete education in the general education and art schools, he developed his own style of writing, at random, saying that in painting, talent is not important, but only zeal will bear fruit. Perhaps, therefore, his self-portrait is so flat as the meaning of the work is large.

Trying to give life to his own image, he bleached the right side of his face, rather, gave a glow with a green povolokoy. This stressed the painful color of the skin. His thinness seems sick. The narrow face is stretched out into the oval, and the cheekbones distinguish the hollows of the sunken cheeks. Eyes of perfect vague color, without glare, without life, without joy, are filled with sadness and depth of experience. Pay attention to the lowered corners of the eyes, as if this person never knew the fun. He did not laugh, distorting his face with mimic wrinkles of joy, “crow’s feet” near his eyes, as it should for many people.

Despite the fact that the self-portrait was written by Vincent in a warm color, there is a lot of bistre, sepia mixed with Berlin azure and soot, hence the work has a cool perception. Van Gogh’s letter itself is neat and smooth. Smears are shaded to shine in the background. His image worked to the smallest detail – wrinkles, glare on the scarf, red hair. A sad image of self-expression weighs the viewer, however, like the life of the artist himself. It can not be said that he was happy, but Vincent’s early self-portraits, nevertheless, are brighter and more joyful in content and color.

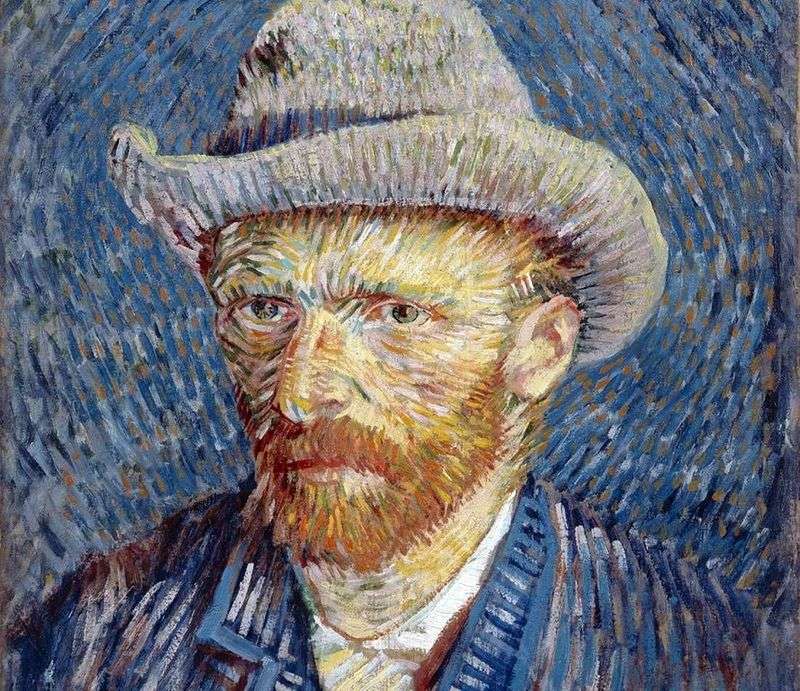

Self-portrait in a gray felt hat III by Vincent Van Gogh

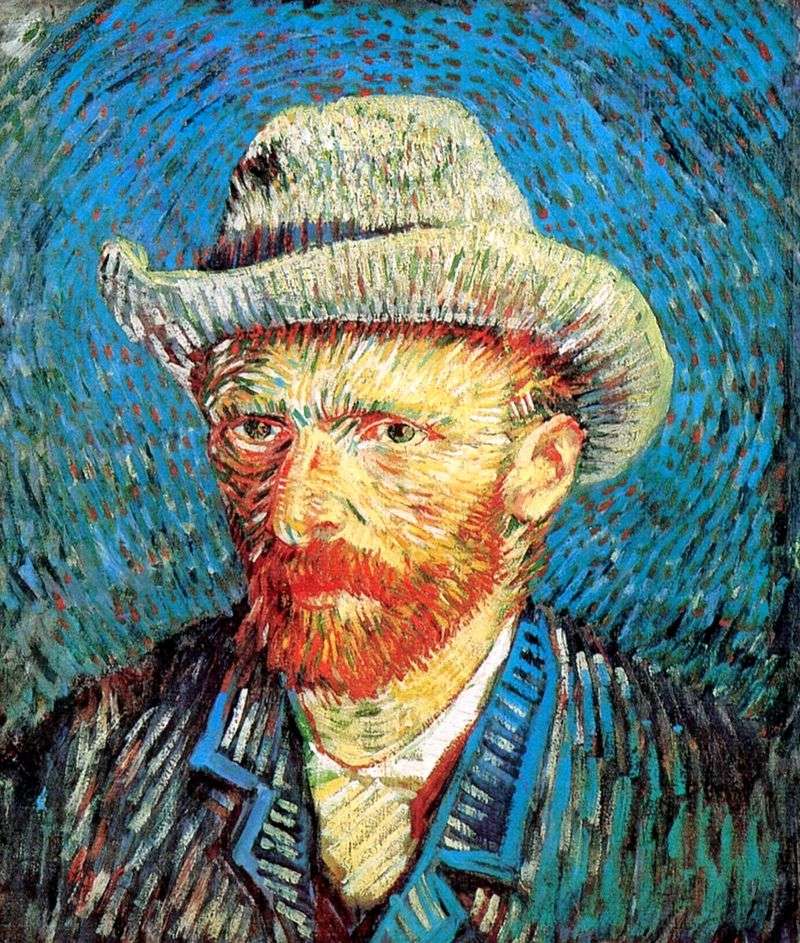

Self-portrait in a gray felt hat III by Vincent Van Gogh Self-portrait in a felt hat by Vincent Van Gogh

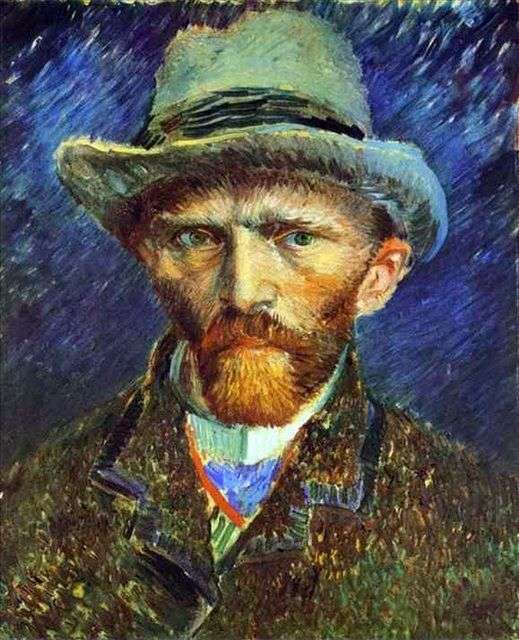

Self-portrait in a felt hat by Vincent Van Gogh Self-portrait in a gray hat by Vincent Van Gogh

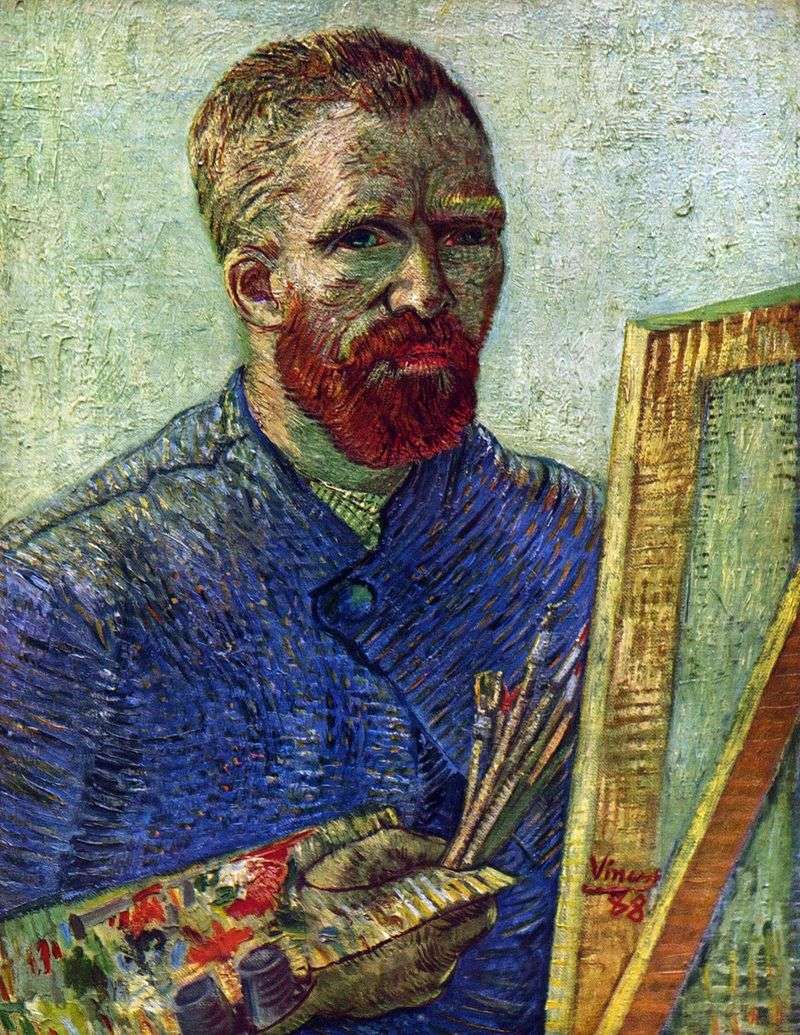

Self-portrait in a gray hat by Vincent Van Gogh Self-portrait in front of the easel by Vincent Van Gogh

Self-portrait in front of the easel by Vincent Van Gogh Portrait of Camille Roulin by Vincent Van Gogh

Portrait of Camille Roulin by Vincent Van Gogh Portrait of a Woman by Vincent Van Gogh

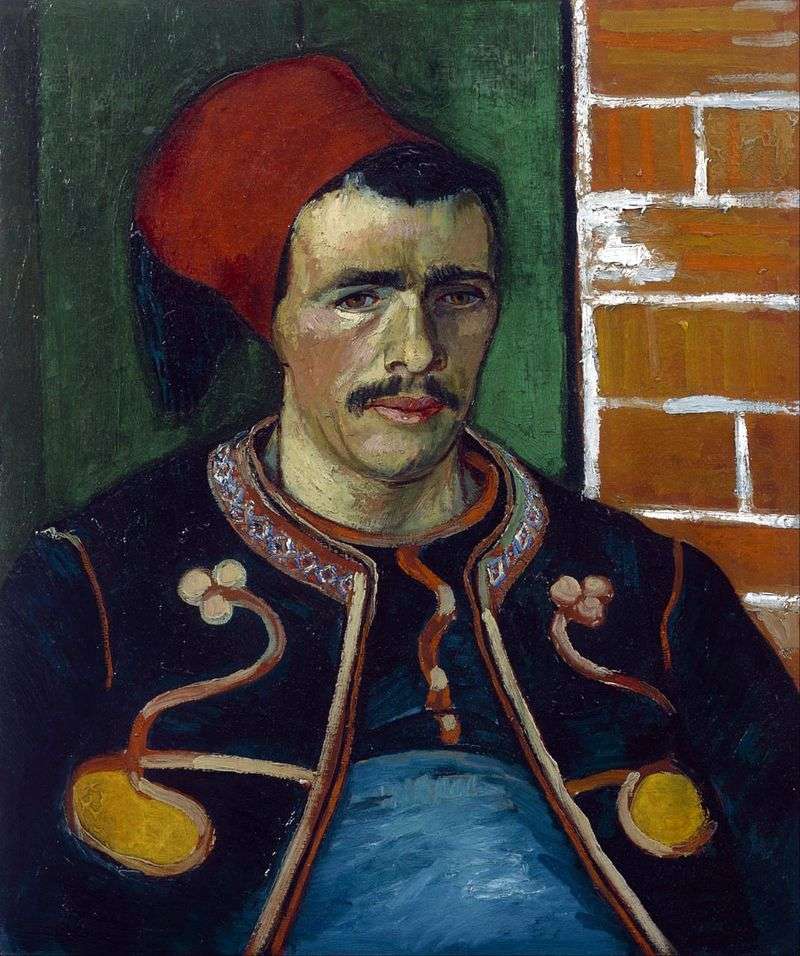

Portrait of a Woman by Vincent Van Gogh Zouav (Belt Portrait) by Vincent Van Gogh

Zouav (Belt Portrait) by Vincent Van Gogh Portrait of Pope Tangi II by Vincent Van Gogh

Portrait of Pope Tangi II by Vincent Van Gogh