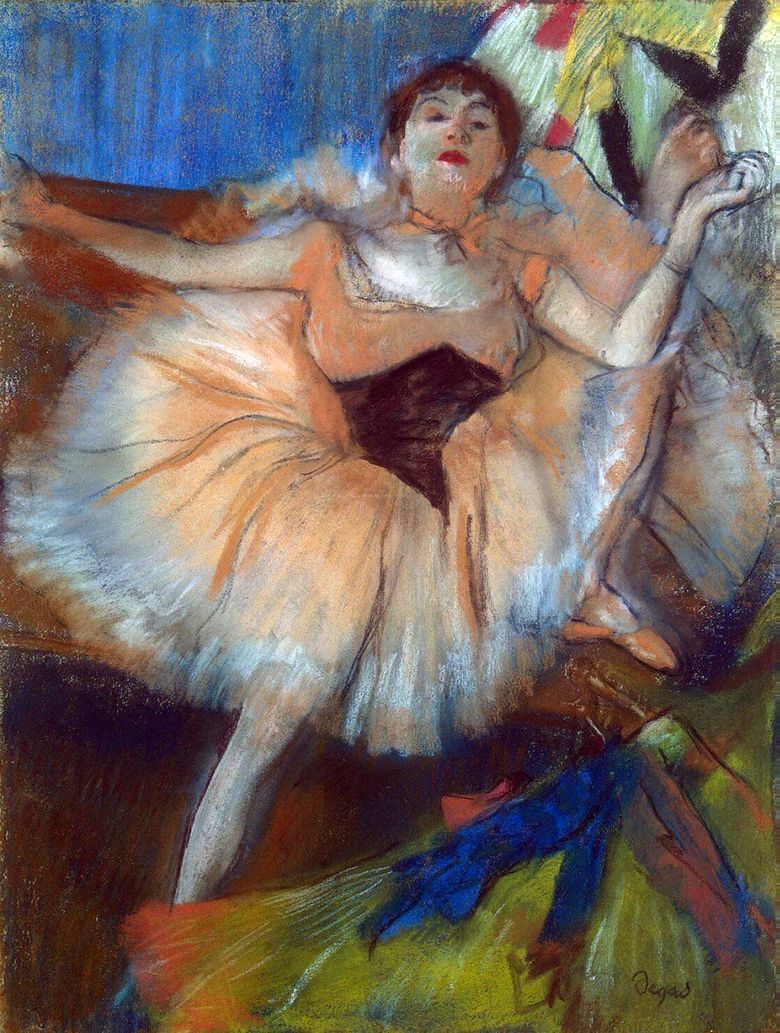

In a similar pose, this model is depicted in the “Resting Dancer” and in the “Lesson of Dance”, for which this pastel, apparently, served as an etude. Lemoine dated both works of 1885, but modern scholars believe that they were performed about five years earlier.

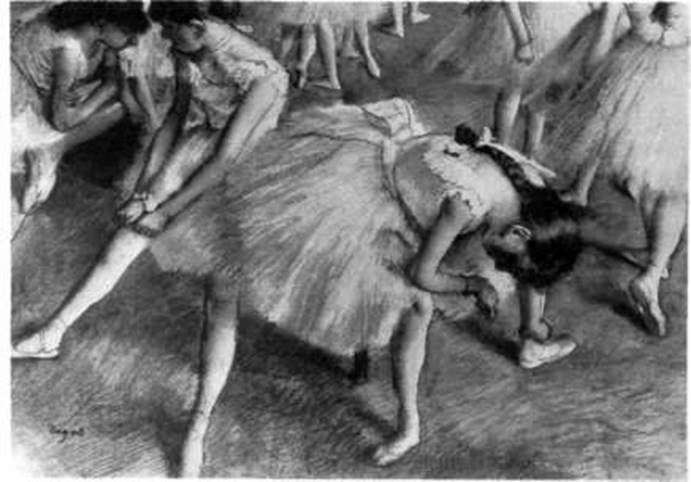

Narrow, horizontally-varying variations of the Lesson of Dance, over which Degas worked already in the late 1870s, show part of the rehearsal room where several dancers of the corps de ballet are engaged in exercises, and one or two rest. This is the picture from coll. Mellon in Upperville. It was shown at the exhibition of the Impressionists in 1880, and it is this fact that allows to correct the Lemoian datings in relation to the whole group of works. Probably, after it was written Williamstown canvas. At the right edge there is a small ballerina, a prototype, which could serve as a “Sitting Dancer”. Her legs are just as well apart, only her hands are lowered. In the Williamstown Lesson of Dance, such a figure, which closes the entire chain of figurants, is called upon to stop the general movement, or rather, the sum of the movements of the dancers,

The variation of the motif developed in the Seated Woman can be considered a charcoal “The Resting Dancer”, also known as the “Resting Coryphaeus”, where the figure is presented not in front, but in three quarters. It was suggested that the second, traditional, name was appropriated ironically. Meanwhile, it does not carry irony, but simply contains a ballet term, which means the dancers of the corps de ballet performing in the first line and performing individual small dances that are not trusted by the ordinary members of the troupe. Velvet on the neck, a little liberty, though admissible on the stage decoration, could rather afford not the dancers of the corps de ballet, but the coryphaeus.

In the pastels “The exit of dancers in masks” “sitting” the heroine of the picture from coll. Krebs is pictured at the moment when she is straightening the neck ribbon. “Exit masks” once again proves that the ballerina presented here and there is not a fictional character, but some real actress of the Paris Opera, she is so portrayed here: a wide flat face, wide-set small eyes, low forehead. One can even assume that Degas asked her to be his model when he worked on these works.

The dancer’s pose is uncomplicated and expresses utter ease. She, perhaps, is not elegant, but it is quite natural that for Degas everything is more important. Similar poses go back to the posture of Giovanna Bellelli in the “Family Portrait”, where the figure placed in the center sits carelessly and deliberately, bending his foot under him, in other words, not at all as required by the conventions of custom portraits (should the youngest daughter be allowed similar and small deviations from “ceremonial.” Later variations of such a pose, in which the dancers already appear, are even more relaxed.

In Deg’s picture, any, even the most unusual position of the body takes shape in such an irreproachable figure, setting such a strong framework that it may seem that the pose as if “pulls” to the lines that control the entire composition. In fact, in a very complex creative process nature, miraculously preserving all its naturalness, is transformed by color and pattern. Color and line condense and acquire almost independent value.

Degas, who said that “a dancer is only a pretext for drawing”, defending himself against superficial judgments about his art, when only a “painter of ballerinas” wanted to see him, deliberately represented the situation in a simplified form. Like no other, he knew and was able to show in paintings and pastels everything that is peculiar to this profession, any nuances of the behavior of “rats”, as they called corps de ballet dances. Phenomenal observation and honesty never allowed an artist to embellish characters. “Sitting dancer” with a flat face, a clumsy figure and a short neck, it is difficult to recognize the beautiful.

However, pastel as a unique combination of color spots is beautiful. Figure – a sample of rare skill. The balance of all elements is supported by a composite solution, the basis of which is the crossing of diagonals. More noticeable is the diagonal, indicated by the line of the right foot of the dancer and the contour of the corsage. The direction of the other diagonal is echoed by the movement of the right hand. In the Williamstown painting, the hand is omitted, its lines, which are continued in the contours of the foot, denote the “obstructing” vertical, which completes the chord of the composition. It is clear that with all the connections to this picture, “Sitting Dancer” can not be recognized as an etude to her. It is a completely independent work with another, only inherent in the dynamics of the picture.

Dancer at the photographer by Edgar Degas

Dancer at the photographer by Edgar Degas Dance lesson by Edgar Degas

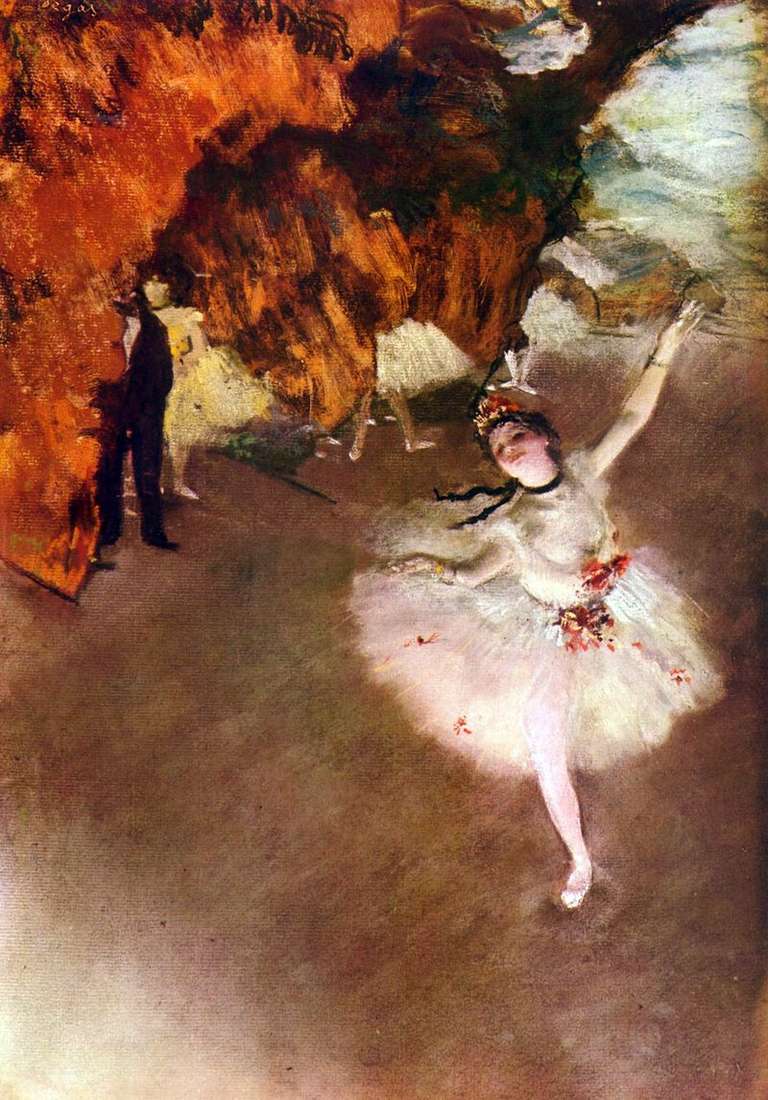

Dance lesson by Edgar Degas Star by Edgar Degas

Star by Edgar Degas Two dancers by Edgar Degas

Two dancers by Edgar Degas Rehearsal by Edgar Degas

Rehearsal by Edgar Degas Dance class (Dance lesson) by Edgar Degas

Dance class (Dance lesson) by Edgar Degas In anticipation of entering the stage by Edgar Degas

In anticipation of entering the stage by Edgar Degas Danseur assis – Edgar Degas

Danseur assis – Edgar Degas