According to Jane Morris, her husband first became interested in embroidery in the mid-1850s, when he began to dissolve his antique swatches, trying to understand the technique, and began experimenting with a wooden frame and combed wool, painted in accordance with his own requirements. The earliest of his known samples was a wall drapery, roughly embroidered with wool, dyed with natural dyes, and the motifs of trees and birds were repeated in the pattern, and the motto of the pseudo-Greek letters “Als Ich Can”, borrowed by the author from the picture by Jan van Eyck, “Portrait of a Man in a red turban “from the collection of the London National Gallery.

While this panel was conceived as an attempt to reproduce the primitive recurring patterns of medieval embroidery, which William Morris carefully studied during his trip to France and the Netherlands, dated 1856, the motifs were borrowed from wall draperies presented in two book illustrations, “Dance forest savages “and” Meeting of the King of France and the Duke of Brittany in Tour “from the manuscript of the Chronicles of Frouassard XV century, with which Morris worked in the British Museum. These details also formed the basis of this product, a fragment of a larger embroidery made in the early 1860s, probably for the Red House: it was presented at the company’s booth at the 1862 World Fair and later entered the Alice Boyd collection, mistresses William Bella Scott, in her Aeshire home of Penkll Castle. Here the embroidery was hung in the gallery of the old part of the building next to another embroidered panel. Both works were referred to by Rossetti in a letter to Boyd of November 1868 as “Topical Tapestries” – a joke based on Morris’s nickname “Tops”. A variation of the same design can be seen on the drapery that adorns the background in Morris’s “La BeNé Iseult” painting.

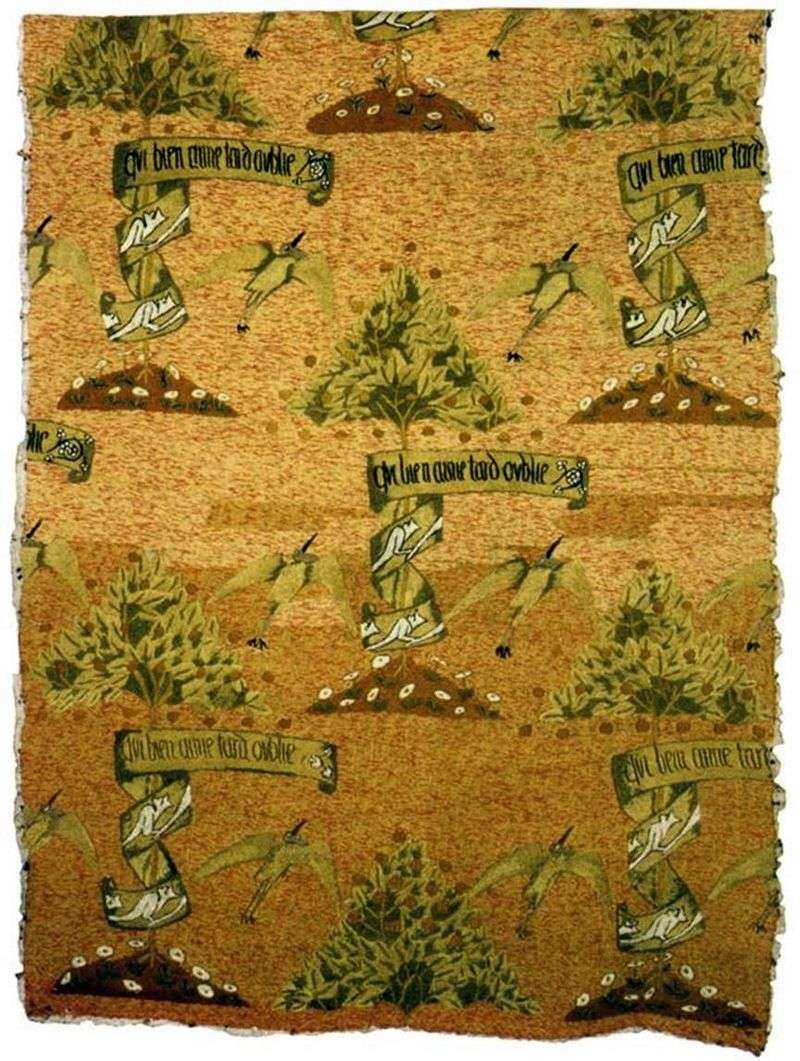

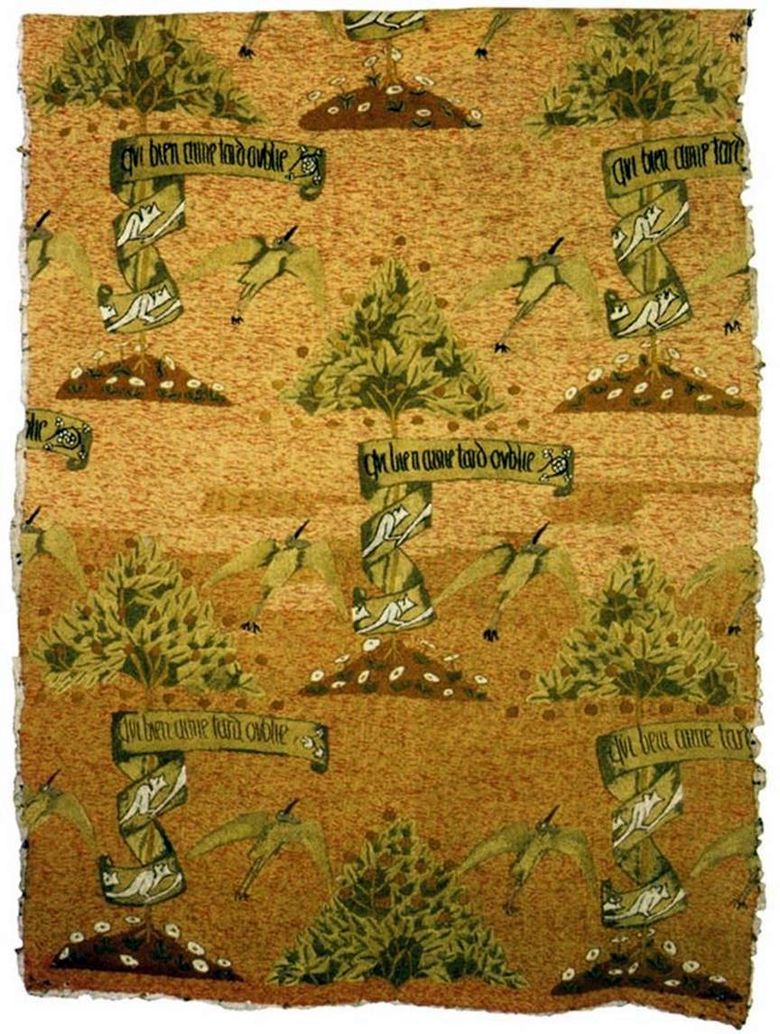

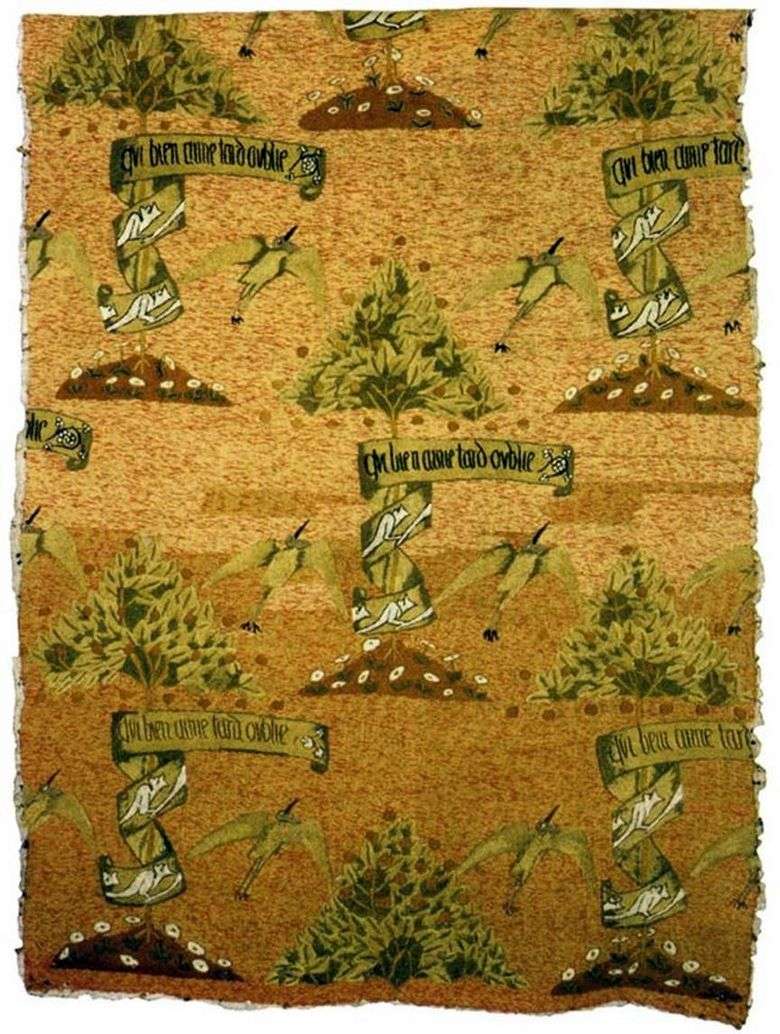

The embroidery repeats the pattern of fruit trees entwined with scrolls, which depict grotesque chameleons and inscribed the words:

“Who loves much, soon forgets”

This is a common proverb, also used as the title of the song in the 14th century by Chaucer’s poem “The Bird’s Parliament”. Each tree rises from a triangular hill of earth dotted with daisies; Between them, herons soar upwards in flight. Linen fabric is used as a plain weave, and embroidery is made of stalked and chain stitches with thick woolen threads of brown, green and cream colors. Orange-yellow and red wool, intertwined together, are used to create the background; The stitches are laid horizontally in the so-called brick order: the effect is enhanced by the use of different dyes in the process of creating the composition. In addition to the natural pigments, synthetic violet paint is also presented here, which was sold only in the early 1860s; what follows

And although the drapery design was created directly by him, it is not known what part of the embroidery was made by the artist himself. Linda Perry determined that at least three craftsmen worked on embroidery, all of them were most likely women from the artist’s closest circle: Jane Morris, her sister Bessie Bearden and, possibly, Georgiana Bern-Jones. While women’s participation undoubtedly confirms the collective nature of the firm’s work and Morris’s conviction that work must bring satisfaction to all participants, regardless of gender, it in no way disproves the traditional association between women’s crafts and copying. This assertion was disputed only later in the same century, when craftswomen such as Mae Morris, Phoebe Tracair and Jessie New-Bury gradually gained a reputation as designers, exactly like craftswomen.

Qui bien aime tard oublie – William Morris

Qui bien aime tard oublie – William Morris Qui bien aime tard oublie – William Morris

Qui bien aime tard oublie – William Morris The Beautiful Isolde by William Morris

The Beautiful Isolde by William Morris La belle Isolde – William Morris

La belle Isolde – William Morris La hermosa Isolda – William Morris

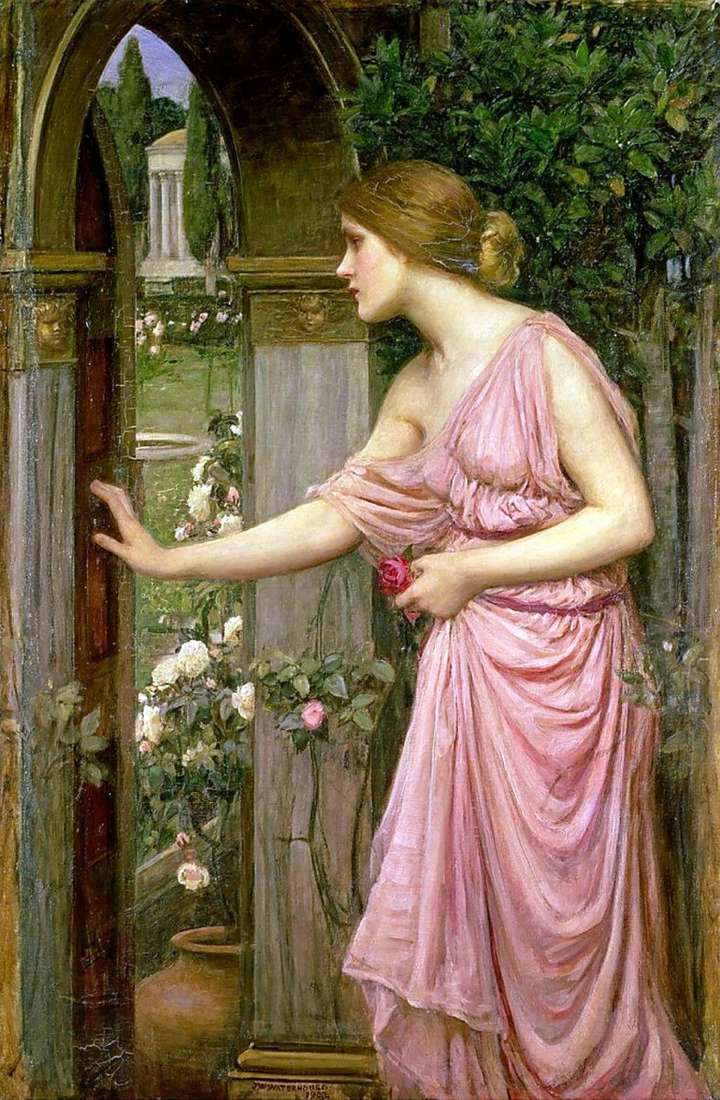

La hermosa Isolda – William Morris Psyche opening the door to Cupid’s garden by John William Waterhouse

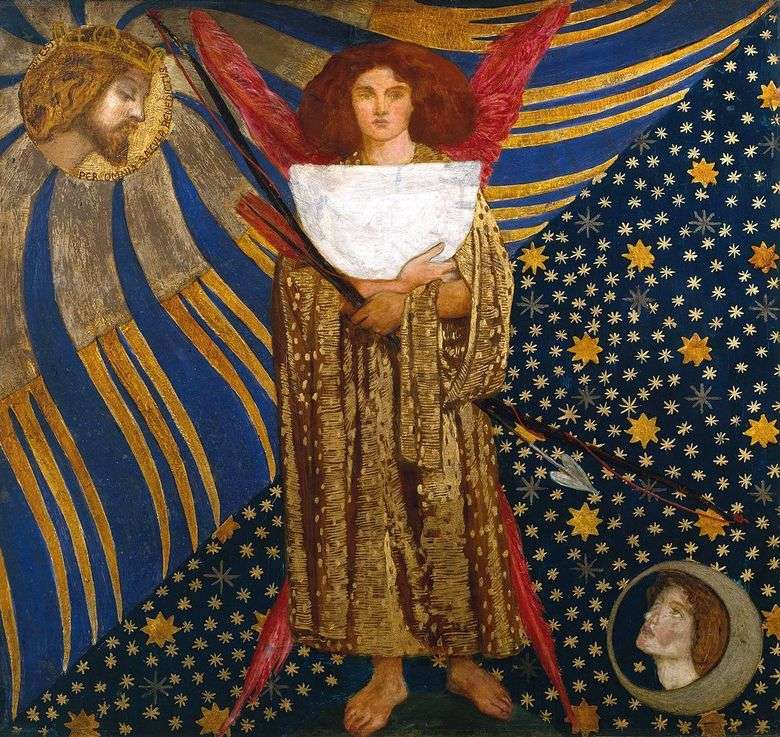

Psyche opening the door to Cupid’s garden by John William Waterhouse El amor de Dante – Dante Rossetti

El amor de Dante – Dante Rossetti Amour Dante – Dante Rossetti

Amour Dante – Dante Rossetti