“Portrait of the father” can be understood only by delving into the details of the biography of Fedotov: the father wipes his glasses, intending to read the newspaper, and this newspaper is not at all simple – this, if you look at the small, carefully written letters, the number of “Russian invalid” from Wednesday December 13, 1833 year, the very day when the son was promoted to ensigns, received the first officer’s rank, the day of the triumph of parental hopes. The portrait was written in Moscow, when Fedotov was vacationed for the first time in three years of service and unheard of for a long time, from August 20 to December 20 – “for domestic reasons,” in fact, in encouraging further work on the picture “Meeting in the camp of the Life Guards Regiment of the Finnish Regiment Grand Duke Mikhail Pavlovich July 8, 1837, “whose sketch pleased Mikhail Pavlovich.

We can say that the “Portrait of the Father” is much more primitive than one would expect from Fedotov in 1837: he is somewhat shy and even clumsy. However, such a retreat is more expensive than other victories. Never before had he tried to portray a real person in details of his actual, albeit insignificant, business and the real situation – a home garden where the old man, feeling a little better, went straight out in his dressing gown and sat down at a simple table, on which he put the newspaper and turned out to be an unnecessary warm cap. Never had he looked at a man with such intense, slow attention and did not force himself, shy of responsibility before nature, neglecting the memorization of skills, pass it exactly as he is. Then something unexpected happened in Fedotov – from another, the future Fedotov.

Andrei Illarionovich, was from simple. The peasant’s surname was issued by Fedotov. “Fedot is not the same,” “Every Fedot has his own care.” The soldier, a private of the Absheron Musketeer Regiment since 1780, he participated in almost all the campaigns and campaigns of the last two decades of the century: in Moldavia during the siege and capture of the town of Khotin; in the Kuban during the Swedish war in Finland, in Poland against the customs rebels, in the Dutch expedition to the fleet in the Baltic and German Seas in England and Holland, where he was wounded with a bullet in his left leg, on the French island at the corps of the Russian troops. And – a broken, chopped, cut, shot, chopped, burned – made its way: in 1794, already a non-commissioned officer, and in 1800 an officer, Lieutenant, however, retired. He would serve and serve, military business was the only thing he knew and knew how, However, the last wound was driven into retirement. By that time, he was already married, and not for the first year, on a captive Turkish woman, taken out of the Moldovan campaign. With his wife and one-year-old son Mikhail, who was born somewhere along the road from the army, he was in 1802 or 1803 in Moscow, where he joined the service as secretary of the Moscow Deanery Department.

It is not known what became of the wife, from whom even the name did not reach us, either she did not suffer the Moscow climate alien to her, or she died in childbirth, producing the next son of Vasily in 1804, or else, but in April 1806 Andrei Illarionovich, who by that time was a widower, married again, on the merchant widow of Natalia Alekseevna Kalashnikova, who was born Grigorieva. He already had his daughter Anna, and in a barely formed family, it turned out that she had three children. As if that was enough, but, sure enough, the father was drawn to family joys, and one after another, the children went: Alexander, Alexei, Pavel, Nadezhda, Ekaterina, Love. However, as if a rock was hanging over them. Vasili died nine years old, Alexander was born sickly and frail, and then went even worse – Alex and Nadezhda died, barely having appeared in the world and get a name, and Catherine – the next year after birth. Paul alone, who was born on June 22, 1815, was healthy and strong, and his future could be hoped for.

The mother had some capital, in 1810 bought a wooden house in the first quarter of the Yauza part, at Khomutovsky Lane, number 80. The house was small: four rooms, five windows on the first floor and three on the mezzanine. Behind the house there was a small plot. In this house, long since already wiped off the face of the earth, and passed the first eleven years of Fedotov’s life. 0 mother we know almost nothing. She was twice married, gave birth to children, died of consumption. How fate pushed her with an elderly, thirty-five-year-old man, unsmiling and lonely, without a penny in his pocket, without relatives, and even with two young children in their arms? What were her character, appearance, habits, range of interests, relationships with others? But Fedotov did not tell us a word or a hint, as if there was nothing to remember, as if she did not exist, as if she had left no trace in him. Father Fedotov described and even partly explained – sparingly, but capaciously.

His fate was special, his nature was peculiar, the marriage itself with a captive Turkish woman testified to the nature capable of acting, and the way he did was about a persistent and persistent character. Life circumstances forged and tempered this character. “Honesty he possessed immensely, but she, like many honest old men who suffered much in life, was clothed in severe, cruel, angular forms…”. People like Fedotov, the father, are not satisfied with the fact that they profess some principles, but they demand the same of others and in communication are extremely difficult. Hard and straightforward, stubbornly retaining the habits acquired by the soldiers’ service, and even separated from his son by the enormous age difference at that time, laconic, not inclined to tenderness, however, and unable to, even if he wanted, to be gentle,

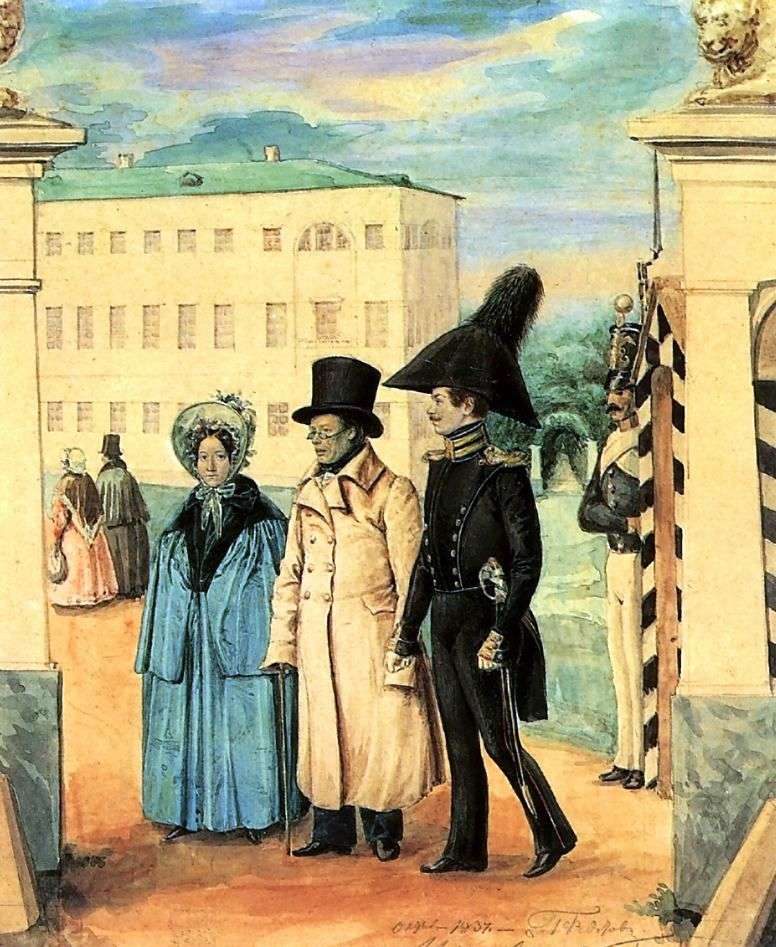

Portrait of MM Rodivanovsky by Pavel Fedotov

Portrait of MM Rodivanovsky by Pavel Fedotov Walking by Pavel Fedotov

Walking by Pavel Fedotov Portrait of E. G. Fluga by Pavel Fedotov

Portrait of E. G. Fluga by Pavel Fedotov Portrait of NP Zhdanovich behind the clavinet by Pavel Fedotov

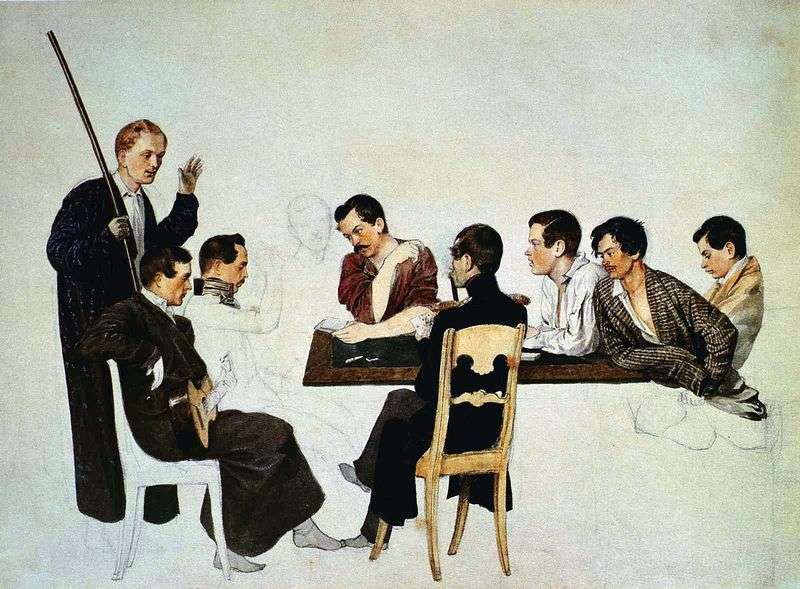

Portrait of NP Zhdanovich behind the clavinet by Pavel Fedotov Fedotov and his colleagues in the Life Guards Finland Regiment by Pavel Fedotov

Fedotov and his colleagues in the Life Guards Finland Regiment by Pavel Fedotov Portrait de M. M. Rodivanovsky – Pavel Fedotov

Portrait de M. M. Rodivanovsky – Pavel Fedotov Portrait of the architect by Pavel Fedotov

Portrait of the architect by Pavel Fedotov Portrait of a father in 70 years by Albrecht Durer

Portrait of a father in 70 years by Albrecht Durer