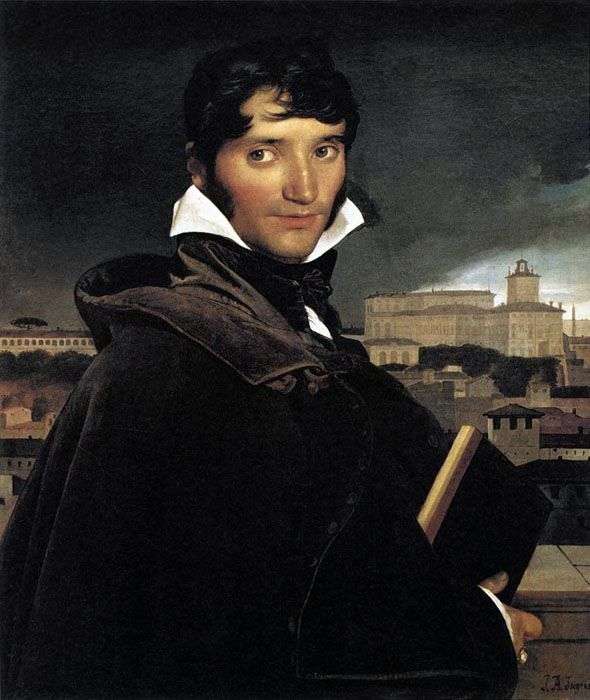

The portrait of the Russian Count ND Guriev Engr wrote in Florence in the spring of 1821. Guryev was the adjutant of Alexander I, in the past – a participant in the Patriotic War of 1812, later – a diplomat. Neither the history nor the memoirs of his contemporaries say much about his personality and activity, apparently, there was nothing outstanding in him. Angru posed uninteresting person with a fairly ungrateful appearance, and yet the artist managed to create a magnificent work of art.

The composition of the portrait is distinguished by noble and strict simplicity: the stable and solid silhouette of the figure sharply separates it from the landscape background and gives it special significance; the proud dignity of the pose, the energetic turn of the head and the spectacular motif of the cloak thrown over his shoulder create an atmosphere of parade elevation. But this traditional formula of the classic representative portrait is clearly slipped by foreign notes. The classic portrait almost always showed the hero balanced and strong, even in moments of pathetic uplift, preserving clarity and firmness of spirit.

Here the balance is lost: the internal tension became exaggerated and restless, the energy does not look like the natural state of the hero, but deliberately accepted the pose, the face turned into an impenetrable mask that hides the character and soul world of the person. Ingres, as a true portraitist of the nineteenth century, is too observant and zorok to preserve the classical tradition of hero idealization; with documentary accuracy he fixes the external and internal mediocrity of the model, and when his brush gives it an external strong-willed power, the image finds itself in the grip of a sharp dissonance. The echoes of this dissonance are felt in the painting of the portrait. Dramatic is his landscape background with a leaden pre-storm sky.

The crimson color of the cloak lining excitedly invades the range of deaf blue-black tones. Engra’s image, as always, is impeccably virtuosic, but his hardness makes all the lines tense, and the cold clarity with which he closes every detail in himself or sharply differentiates color spots causes an anxious feeling of estrangement, disunity of forms. In this excellent canvas, hand in hand are classical slenderness and refinement of high craftsmanship, ruthless analyticity and romantically aggravated discord in the worldview. Like many other works of Ingres, it bears the imprint of the contradictions of a turning-point, in which the outstanding master worked. The picture came from the collection of AN Naryshkina in Petrograd in 1922.

Portrait of the artist François Marius Graine by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres

Portrait of the artist François Marius Graine by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres Portrait du comte N. D. Guriev – Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres

Portrait du comte N. D. Guriev – Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres Portrait of Mademoiselle Riviere by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres

Portrait of Mademoiselle Riviere by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres Retrato del conde N. D. Guriev – Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres

Retrato del conde N. D. Guriev – Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres Madonna in front of a cup with participle by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres

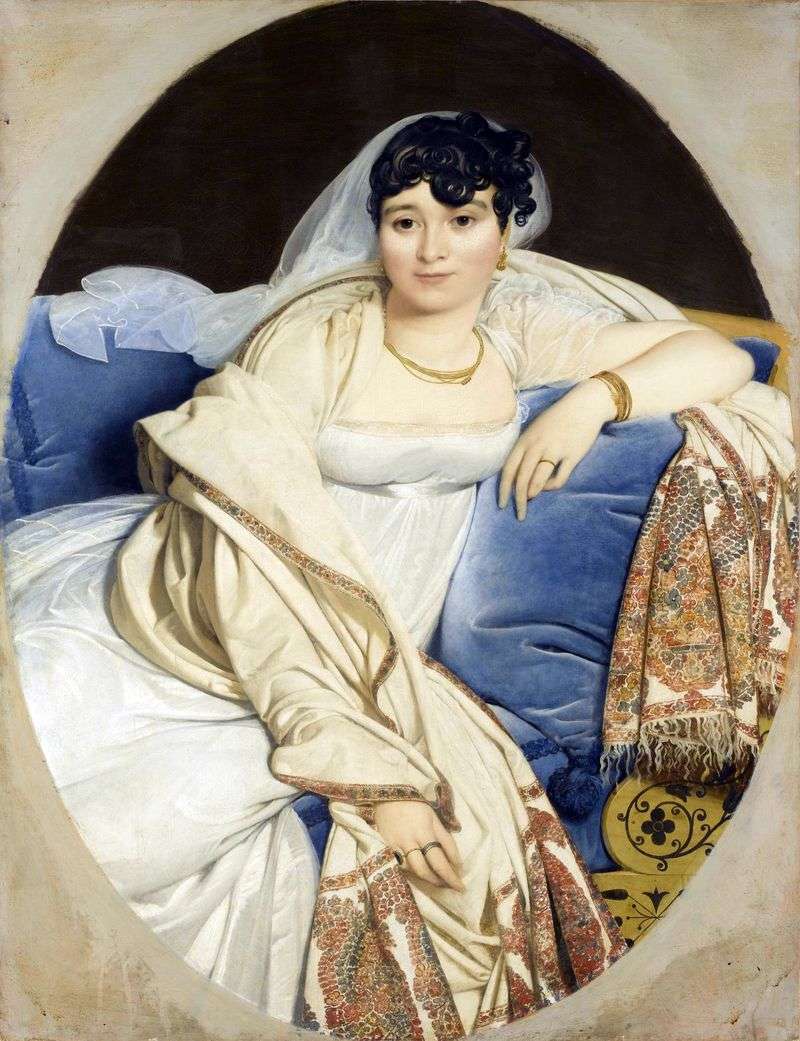

Madonna in front of a cup with participle by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres Portrait of Mrs. Riviere by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres

Portrait of Mrs. Riviere by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres Portrait of Mr. Forest by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres

Portrait of Mr. Forest by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres The Martyrdom of Saint Symphorion by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres

The Martyrdom of Saint Symphorion by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres