MELANHTON, PHILIP, a German humanist, an evangelical reformer and the first systematic theologian of Lutheranism. Melanchthon was born on February 16, 1497 in Bretten. He was a grand-nephew of the famous humanist and Hebraist Johann Reichlin and, at his insistence, enrolled in the Latin school in Pforzheim, and then at the universities of Heidelberg and Tübingen, in the latter he began his teaching career. Melanchthon studied the works of Plato, Aristotle, William Occam.

Before acquaintance with Luther, he studied in depth scholastic theology and ecclesiastical ethics. August 25, 1518 Melanchthon came to Wittenberg, where he successfully taught both classical and theological disciplines, defending the evangelical truth through Renaissance humanism. Soon he acquired the authority of one of the leaders of the Reformation. His work The Basic Truths of Theology was the first treatise on Protestant theology.

With the Reichstag in Speyer and to death, he was the main representative of the Protestant circles on all major religious disputes. In 1528, his initial education program and other pedagogical undertakings cemented the fame of the founder of the Protestant people’s schools. He did a lot of preparation of teachers, wrote textbooks and promoted the reorganization of numerous schools and universities – it is no accident that the honorary nickname praeceptor Germaniae was attached to him. In his Augsburg confession, the main Protestant creed, Melanchthon sought to reconcile Protestants and Catholics, explaining the evangelical truth and urging the need to preserve the unity of Christians.

Outstanding theological work was his Apology of the Augsburg Confession. The differences in the views of Melanchthon and Luther were reduced to three points. 1) If Luther spoke of “justification by faith alone,” Melanchthon omitted the word “only” in this combination and emphasized the importance of good works as a necessary fruit of faith, though not its cause. 2) In 1527, he revised his attitude to the “stoic determinism” underlying the doctrine of predestination, and the new edition of Loci communes testifies that he at all refused rigid determinism. Proceeding from moral responsibility and his understanding of the Scriptures, Melanchthon insisted that man should accept divine love as the free gift of God. He calls the three co-operative causes of conversion – the Word of God,

This concept was often criticized, because it saw the idea that a person is able to promote his own salvation. 3) Melanchthon did not share Luther’s teachings about the “real presence” of Christ in the Eucharist. After 1530 he developed a doctrinal concept of “a real spiritual presence.” Disputes about the doctrine of the Eucharist threatened his friendship with Luther, later he was accused of crypto-Calvinism. In 1548, in a dispute over “indifferent” things, Melanchthon firmly adhered to his own and former Lutheran views: justification by faith in Scripture is the main thing, other things are permissible. Lutheran theologian Flatsy Illyric, an opponent of the humanists, accused him of heresy and apostasy. Melanchthon died in Wittenberg on April 19, 1560.

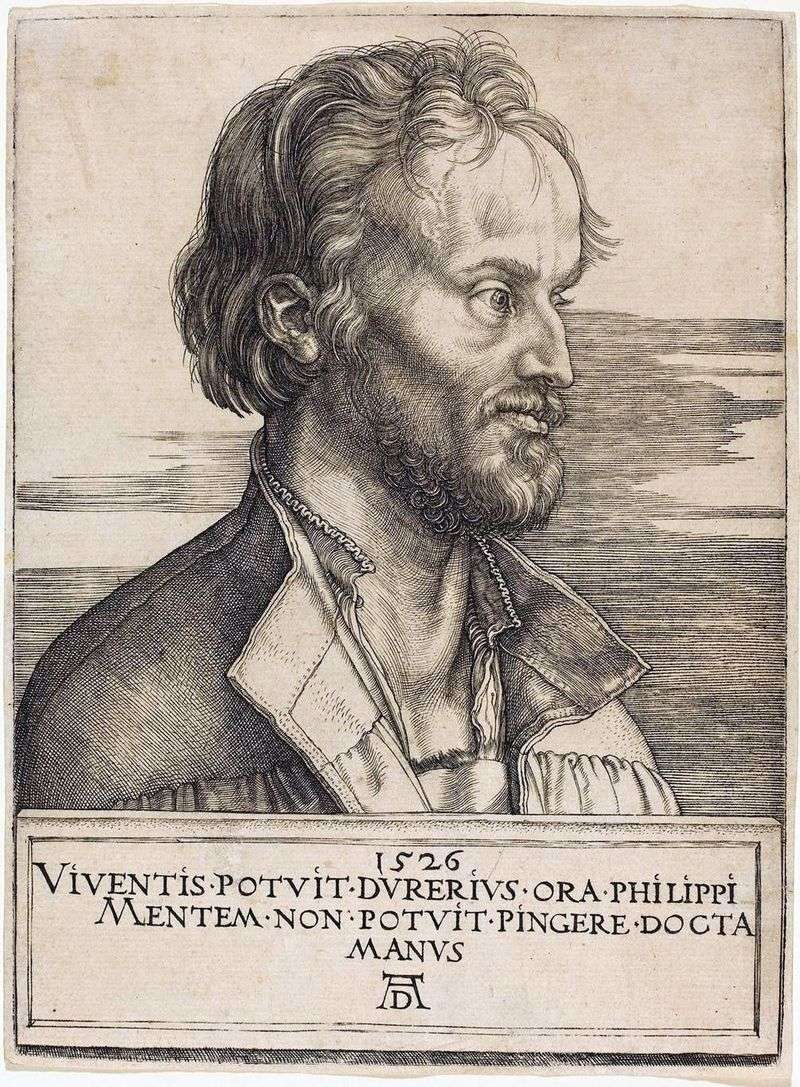

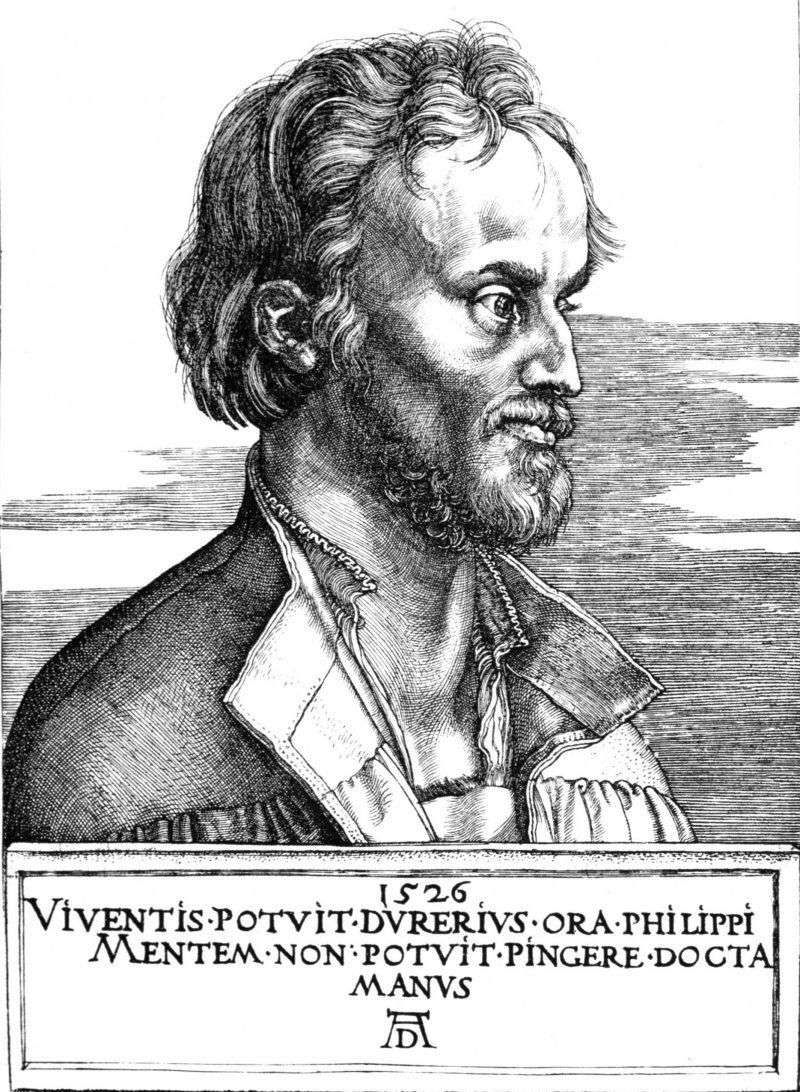

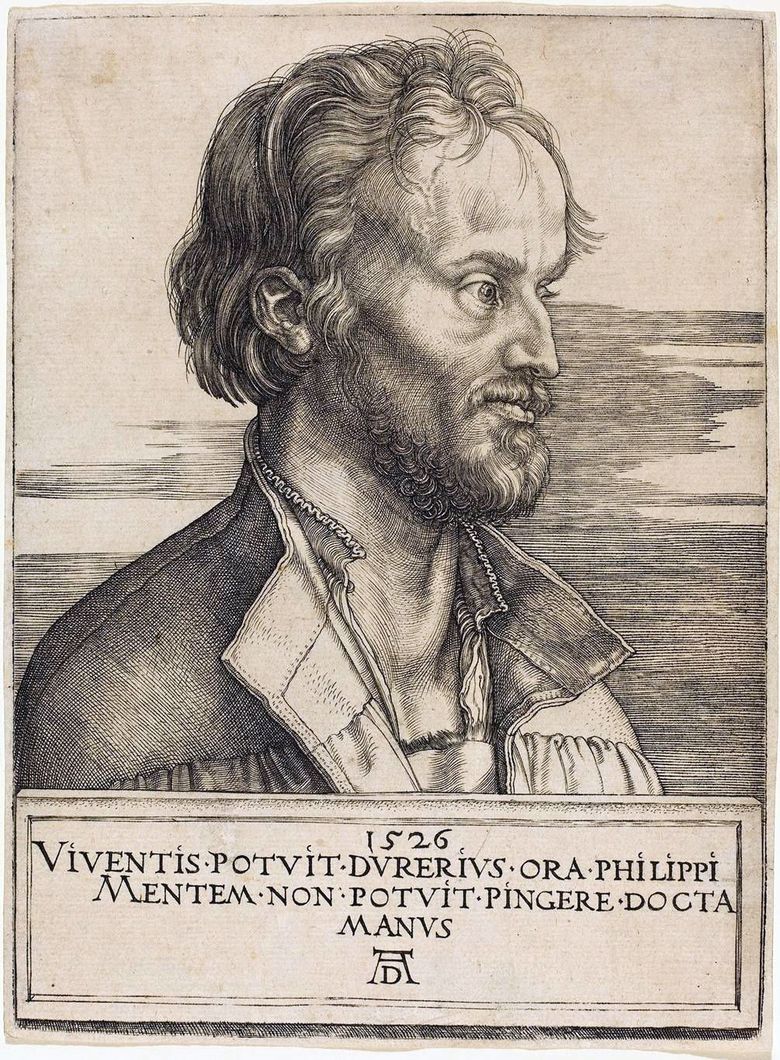

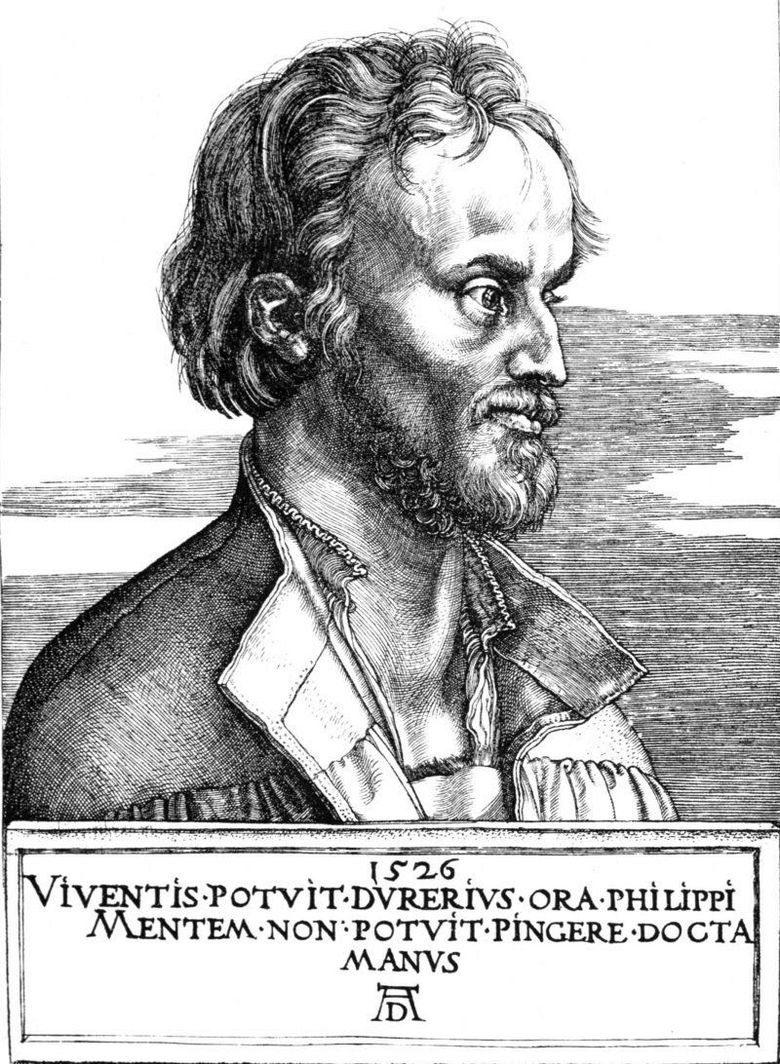

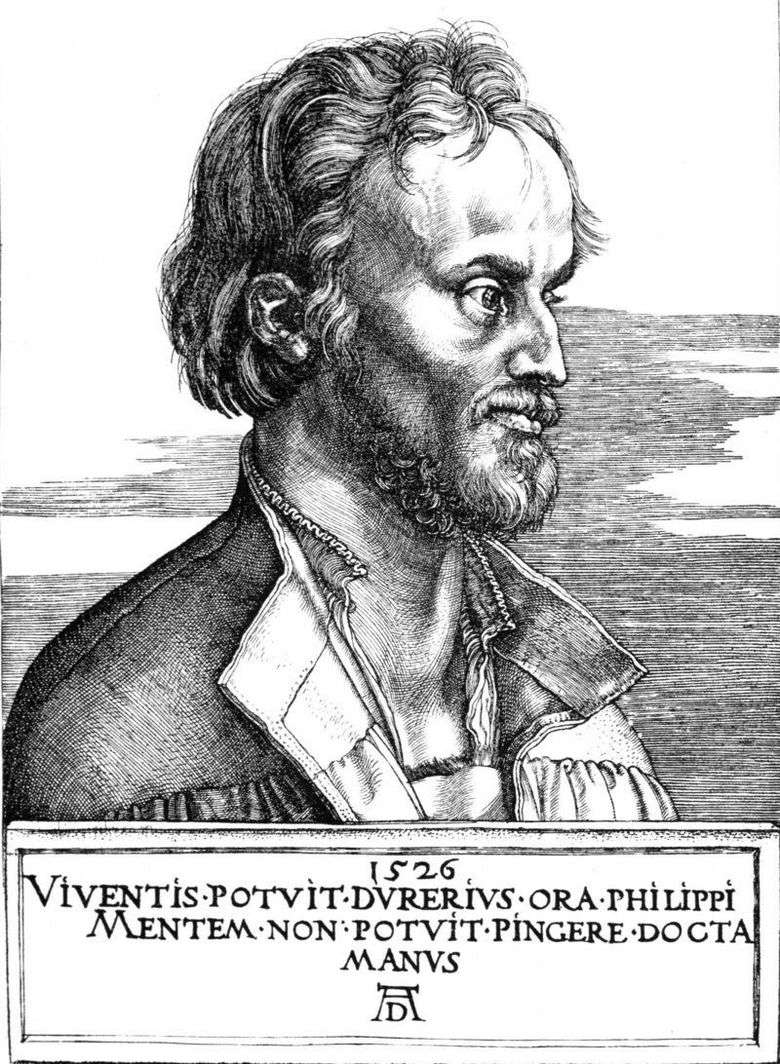

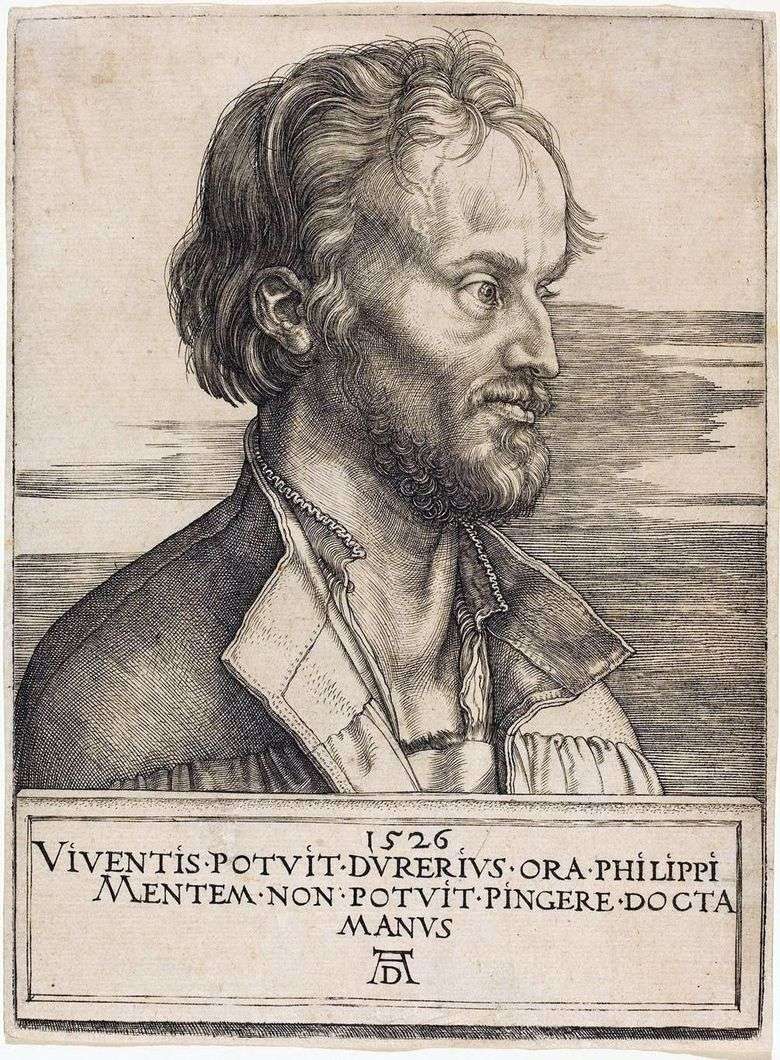

Portrait of Philip Melanchthon by Albrecht Durer

Portrait of Philip Melanchthon by Albrecht Durer Philip Melanchthon – Albrecht Durer

Philip Melanchthon – Albrecht Durer Portrait de Philip Melanchthon – Albrecht Durer

Portrait de Philip Melanchthon – Albrecht Durer Retrato de Philip Melanchthon – Albrecht Durer

Retrato de Philip Melanchthon – Albrecht Durer Philip Melanchthon – Albrecht Durer

Philip Melanchthon – Albrecht Durer Portrait of Martin Luther in the image of the knight of Jorg by Lucas Cranach

Portrait of Martin Luther in the image of the knight of Jorg by Lucas Cranach Suicide of Lucretia by Albrecht Durer

Suicide of Lucretia by Albrecht Durer Ecce Homo or Xie Man! by Albrecht Durer

Ecce Homo or Xie Man! by Albrecht Durer