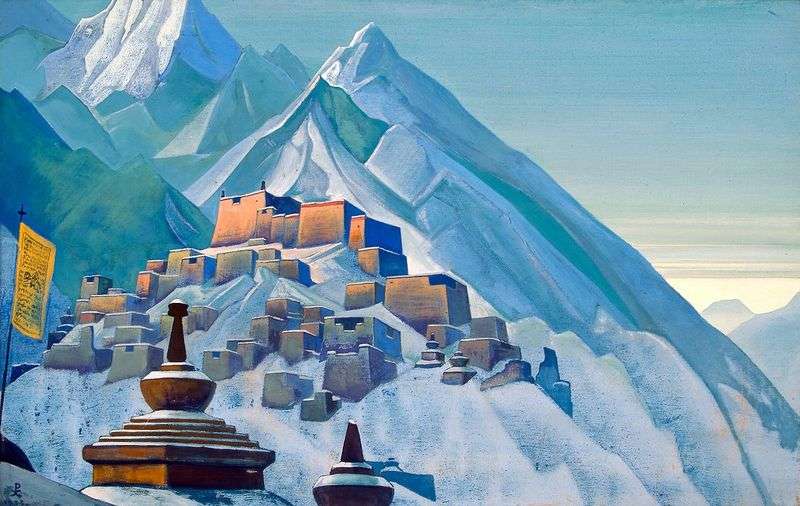

The search for beauty and knowledge, spiritual interests determined the beginning of a new page in the life and work of Roerich. In December 1923, he arrived in India. After reading in a short time from a number of its attractions, with the oldest Buddhist monuments, Roerich rushed to the Himalayas, the highest mountain range of the world with eleven peaks, going up more than eight thousand meters. In the eastern part of the Himalayas there was the princedom Sikkim with old monasteries that attracted the artist.

The long-awaited meeting with the Himalayas held here inspired him. “No one will tell,” the artist wrote, “that the Himalayas are cramps, it will not occur to anyone to point out that this is a gloomy gate, no one will say, recalling the Himalayas, the word is monotony. Truly an entire part of the human dictionary will be left when you enter the kingdom of the snows of Himalayan. And it will be forgotten precisely the gloomy and boring part of the dictionary. “

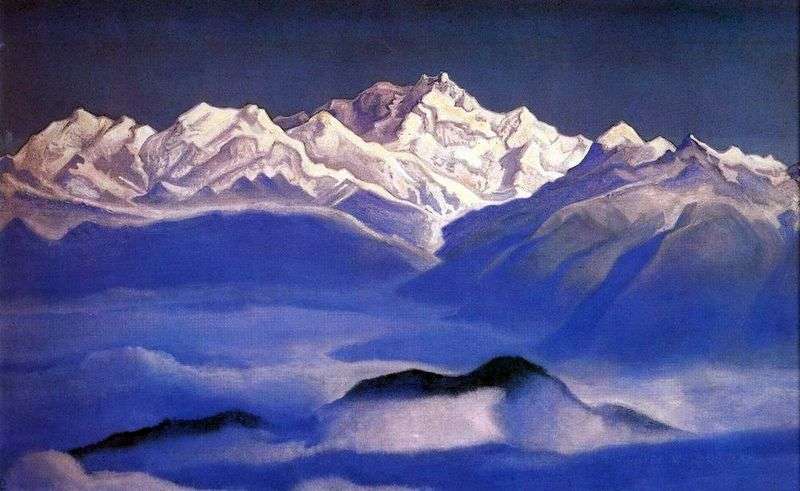

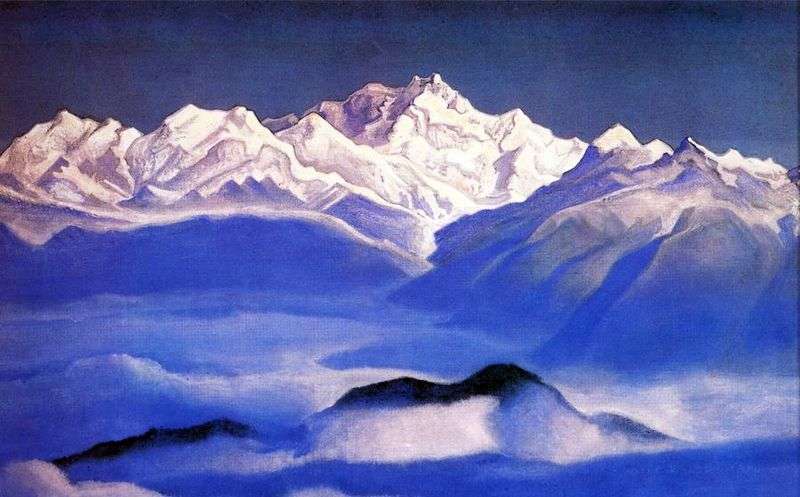

One of the first impressions of the artist was associated with his feeling of two worlds expressed in the Himalayas: “One is the world of the earth, full of local charms… And all this earthly wealth goes into the blue mist of the mountainous distance. The ridge of clouds covers the frowning mist. It is strange it is amazing to see a new supra-cloudy structure after this finished picture. Bright snow is shining over dusk, over cloud waves… Two separate worlds separated by mist. “

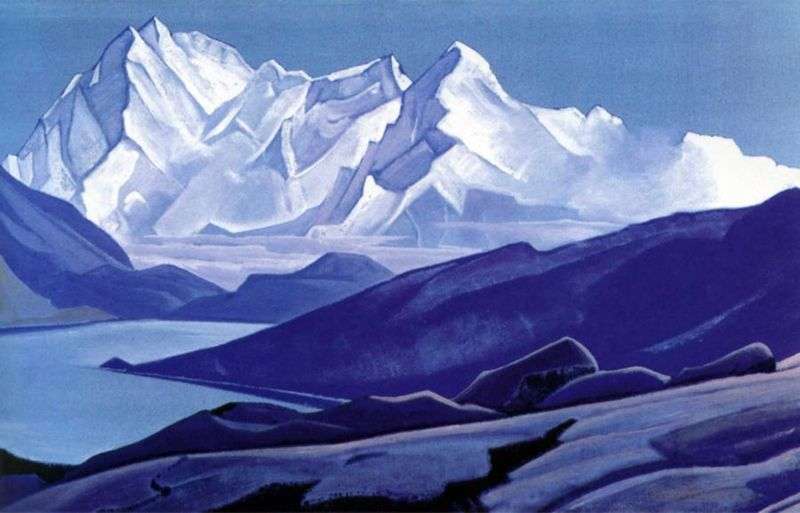

In the paintings and sketches Roerich appears, above all, as the creator of the wonderful landscapes of the world of mountains. It was not without reason that he was amazed by the inexhaustible rich forms of rocks, the fantasy of their heaps, the endless wealth of colors – mountains of blue, crimson, velvet-brown, yellow-fiery and others, and above them – blue sky, almost pure cobalt, against which “distant peaks are cut brightly and white cones. ” Fixing all this in a word, Roerich tirelessly imprinted the beauty of the mountains in his painting.

Most often he wrote the Himalayas, inspired by the majestic spectacle of their shining snowy peaks, the cosmic power of the mountain giants, the magnitude of the manifestation of the natural forces that once formed the very face of the Earth. “The best beauties of nature,” he argued, “were created at the site of the earth’s former shocks… Endless beauty is given by the convulsions of the cosmos.” The Himalayas – “the abode of snow” – appear in his image in the inexhaustible wealth of motifs, in the endless changes of the powerful outlines of peaks and spurs. With enthusiasm, he wrote, from different points of view and in different light, the highest mountains of the world – Everest, Nanda-Devi, especially the five-mounding city of Kanchenjungu, the “treasure of snows”, which is beloved by him. According to local beliefs, she is the embodiment of a deity, riding on a snow leopard.

Roerich wrote the mountains of Lahula, rising to the north of Kulu, where he lived, and many times – mountains, heaving over Kulu; He depicted snow in the mountains and waves of clouds between the mountains, wrote mountain lakes surrounded by legends about their inhabitants – Nagas – wise serpents, and, as if spellbound, imprinted mountain peaks in the evening with golden clouds above them, in the morning, when the peaks are illuminated by the sun, in the afternoon their clear forms, the night with the surrounding radiance or in the greenish nightly glow, when large southern stars appear above the mountains. Roerich did not cease to admire the mountains themselves, and their ability to elevate the human spirit by their one grand appearance: “Mountains, mountains! What magnetism is hidden in you! What symbol of tranquility lies in each sparkling peak. The bravest legends are born near the mountains.” He confessed

Roerich’s palette seems inexhaustible – from deep velvety blue tones to purple, golden, silvery-“moon” ebbs, ineffable with words of shades. He uses the contrasts of pure, unmixed paints that are favored in the East, subtly develops the nuances of the same tone in a European way, and achieves a deep luminescence of multi-layered color overlays. Roerich masterly used the variety of textural properties of the pictorial base, as well as the specifics of tempera that covered it.

Often he kneaded it according to the recipes of Eastern masters on special adhesives and resins. The formats for his paintings and studies he chose most often horizontal, to emphasize the length of the mountain ranges; the space was built, depicting mountains as if by color backstage, often “omitting” a number of plans between the closest and furthest images. In general, he loved the “distant” images, flattening the volumes and giving rich possibilities to his favorite decorative methods. Roerich was able to expressively compare the scale of objects in order to give a feeling of power and grandeur of the depicted mountain range or a wide panorama of the mountains stretching into the bluish haze of distances.

Monumentality organically inherent in his work, it is peculiar to the paintings, and small sketches. The artist skillfully knew how to simplify and generalize the forms, “strike out” the details, build compact compositions. Whatever the size of the work, it has qualities that could allow it to increase to the size of panels or frescoes. In this sense, Roerich’s landscapes are akin to a picture with a heroic sound. Used materials of the book: V. Volodarsky “Nicholas Roerich” White City, 202

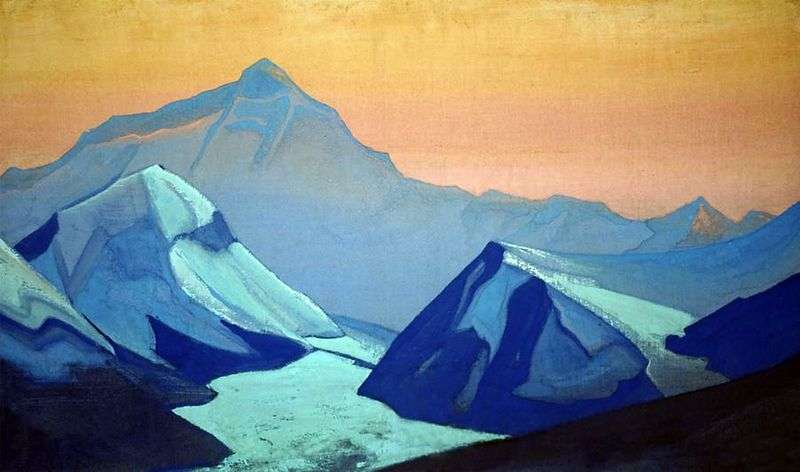

Himalayas. Pink Mountains by Nicholas Roerich

Himalayas. Pink Mountains by Nicholas Roerich Blue Mountains by Nicholas Roerich

Blue Mountains by Nicholas Roerich Pink Mountains by Nicholas Roerich

Pink Mountains by Nicholas Roerich Sacred Himalayas by Nicholas Roerich

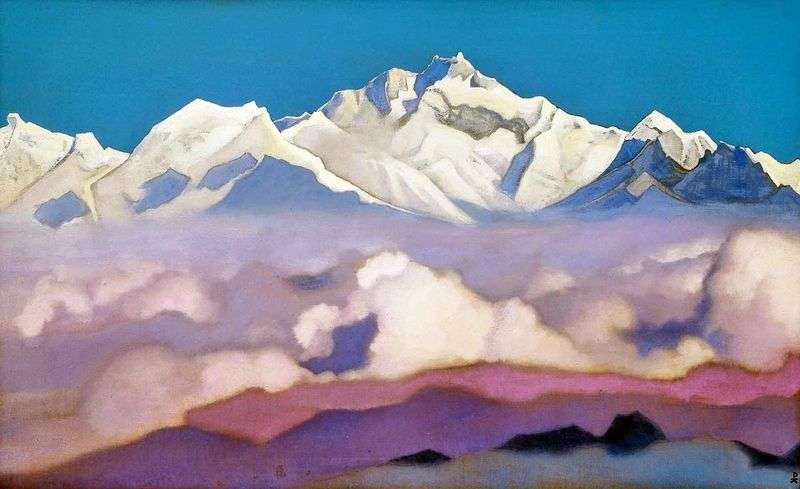

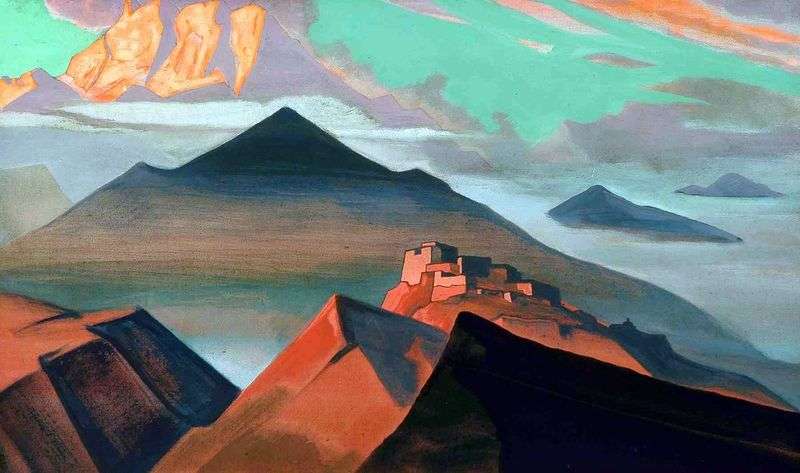

Sacred Himalayas by Nicholas Roerich Tibet. Himalayas by Nicholas Roerich

Tibet. Himalayas by Nicholas Roerich Himalayas Everest by Nicholas Roerich

Himalayas Everest by Nicholas Roerich Kanchenjunga by Nicholas Roerich

Kanchenjunga by Nicholas Roerich Tent Mountain by Nicholas Roerich

Tent Mountain by Nicholas Roerich