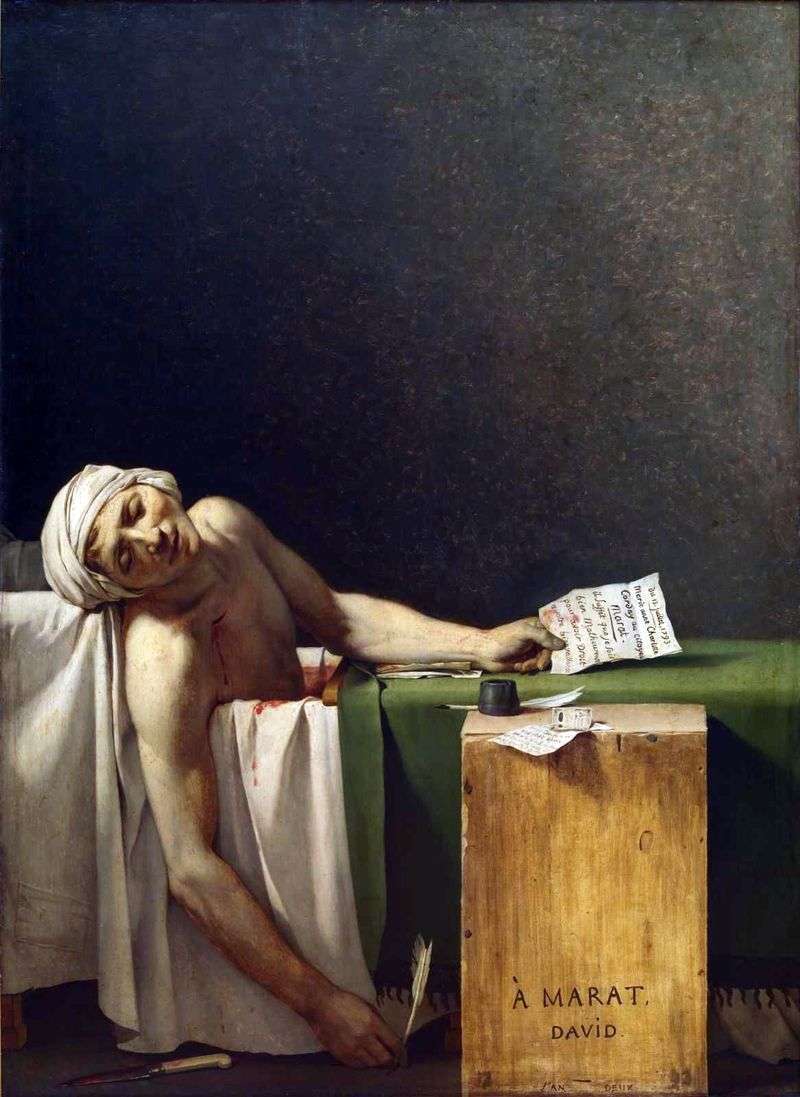

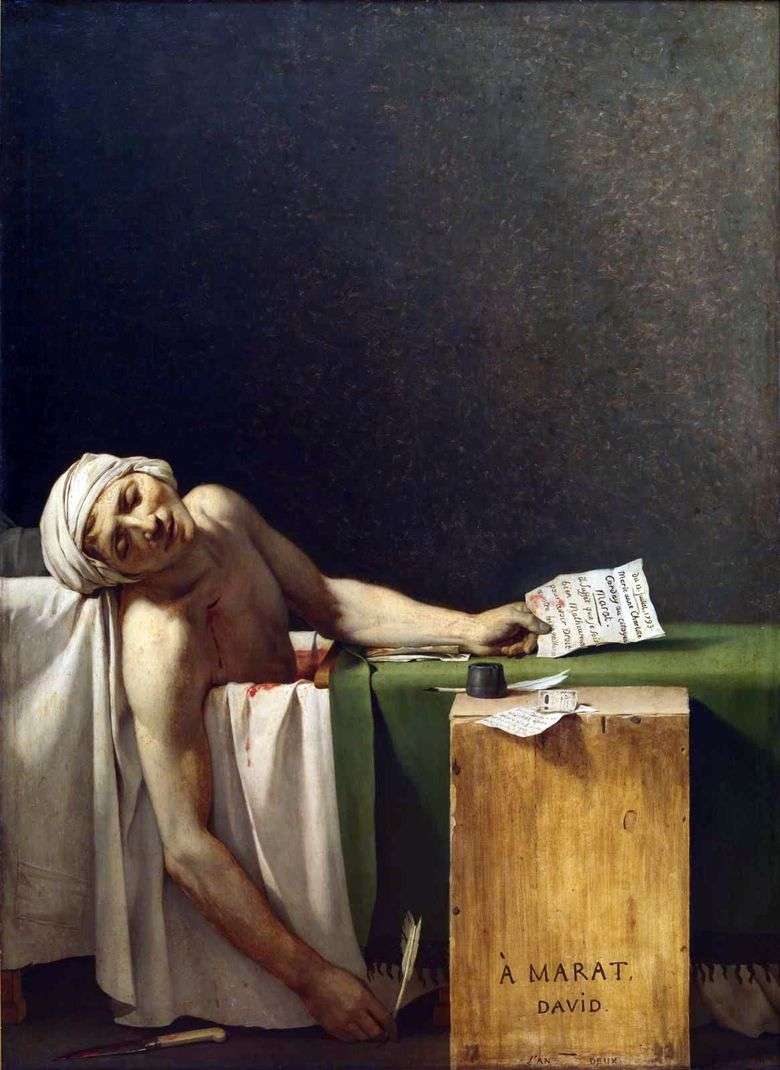

David’s painting “The Death of Marat” depicts an event that deeply shocked public opinion in France in 1793 gol. On the thirteenth of July, the revolutionary Jean Paul Marat was killed in his own home by Charlotte Corday, a young aristocrat, a supporter of the Girondins. Referring to the need to convey secret information to Marat, the woman insisted that he accept her personally. Admitted to the room where Marat used to take a bath every day, she stabbed him with a knife, while he was writing while sitting in the water. The woman was immediately arrested and guillotined three days later.

In the picture, the victim acts as a great historical example. In conveying the essence of the event, the artist abandoned the eloquence and energetic style of his early works on the historical plot and immortalized the memory of his friend Jean Maratha, with whom he met only the day before the atrocity, in the image of an agonizing Christ, taken from religious iconography. The canvas is a civil message and at the same time a tribute to politics and a friend.

The painting was ordered by Jacques Louis David immediately after the death of Marat. It is signed: “Maratou – David, Year Two”. This work was completed in October 1793, or in the Second year, in the month of Wendemiry according to the revolutionary calendar, which came into force in 1791.

Marat is depicted lifeless, in a tub, taking that, he was treating the skin disease that pestered him. A deep wound is clearly visible. The reclining right hand still holds the pen, and the left one squeezes the “insidious letter” given to him by the murderer: “Mary Anna Charlotte Corday to the citizen of Marat. I’m very unhappy, and that’s enough to provide me with your disposition.”

In the painting, striking with the unyielding veracity of the narrative, there is a hidden hint of religious iconography: the deceased is likened to the Christ who was removed from the cross. It is an emblematic figure in which a person associates with his destiny, his illness and terrible death, who overtook him at the highest moment of existence: intellectual labor in the service of the revolution. It clearly affects the desire to create a secular icon. A mortal wound in the chest, a bath, a feather, an inkwell and a wooden box are treated by the artist as emblems of identification and martyrdom of the victim.

David executed from the picture two copies, traces of which were immediately lost. They were invented after his death at the apartment of the artist Antoine Jean Gro, one of the best disciples of David, who was also the official requisition for works of art intended for the collection of Napoleon. In 1835, the grandson of the artist Jules David bought the original painting from his aunt, Baroness Meunier. In 1885, a copy of the painting by Paul Durand-Ruelle came into his hands, and in 1889 he initiated a sensational trial against the widow of Jules David, claiming that he owned the canvas with the original composition. In 1893 the picture of Jules David’s widow entered the Museum’s collection in Brussels, while the other was acquired by the National Museum of Versailles.

Death of Marat by Jacques-Louis David

Death of Marat by Jacques-Louis David Muerte de Marat – Jacques-Louis David

Muerte de Marat – Jacques-Louis David La mort de Marat – Jacques-Louis David

La mort de Marat – Jacques-Louis David Distribution of eagles by Jacques Louis David

Distribution of eagles by Jacques Louis David Margarita-Charlotte David by Jacques Louis David

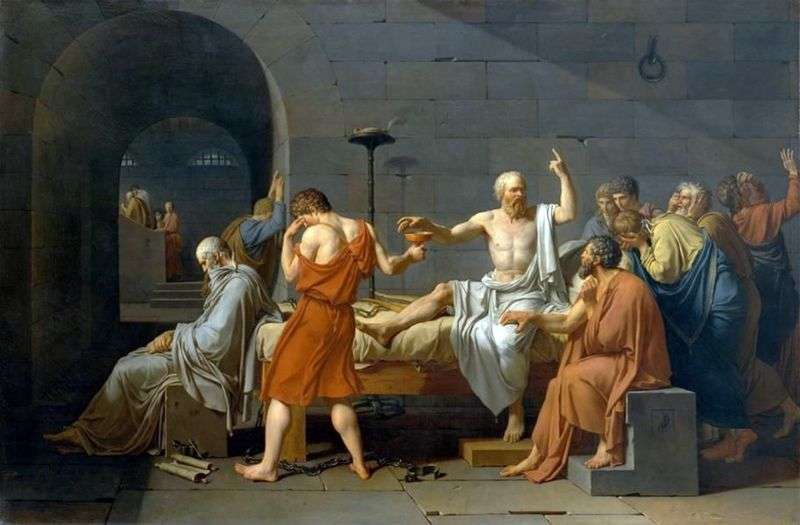

Margarita-Charlotte David by Jacques Louis David The death of Socrates by Jacques Louis David

The death of Socrates by Jacques Louis David Zinaida and Charlotte Bonaparte by Jacques Louis David

Zinaida and Charlotte Bonaparte by Jacques Louis David Portrait of Madame Emilia Serizia by Jacques Louis David

Portrait of Madame Emilia Serizia by Jacques Louis David