As it is easy to guess from the name of the picture, in front of us is an allegory of human life. Four dancing figures personify the four stages of a person’s earthly journey. But in vain the viewer is waiting to see in front of him Childhood, Youth, Maturity and Old Age. Such a distribution of roles would be customary, but Poussin goes a different way. He begins the “life line” of poverty, leads it through Labor to Wealth, then to Pleasure. And closing the circle, once again returns her to poverty. The remaining details and figures present on the canvas are quite traditional.

On the left is a statue of the two-faced god Janus, looking both to the past and to the future. At the pedestal sits a baby, amused by blowing bubbles. On the right is the easily recognizable winged Chronos. To the sounds of his music, dancers perform their dance. At the feet of Chronos another baby is located. He is holding an hourglass counting down the moments of human life. Poussin worked on this canvas for quite a long time, rewriting many details several times.

The greatest processing, as shown by a study of the picture in X-rays, has undergone the Pleasure, depicted as a woman looking slyly at the viewer in a blue tunic. At first, Poussin removed her head with peacock feathers. Then, apparently not wanting to overload the picture space with symbols, he eliminated the feathers, replacing them with a wreath of roses.

In general, compared with the original version, the figure of Delight appeared before the viewer in a more modest form. Poussin diligently “retouched” the naked lust and sensuality flowing through her. These features did not disappear even in the final version, but now they seem to have faded into the background, and the image itself has become, so to speak, “generalized-hedonistic”.

Rewriting the artist and the folds of the tunic. They look more static than originally intended. A curious method by which Poussin created an invoice that allows you to best convey the effects of lighting. In those places of the canvas, where it was necessary, the master applied the paint not with a brush, but with his thumb, “pressing” it to the wet ground.

Repentance by Nicolas Poussin

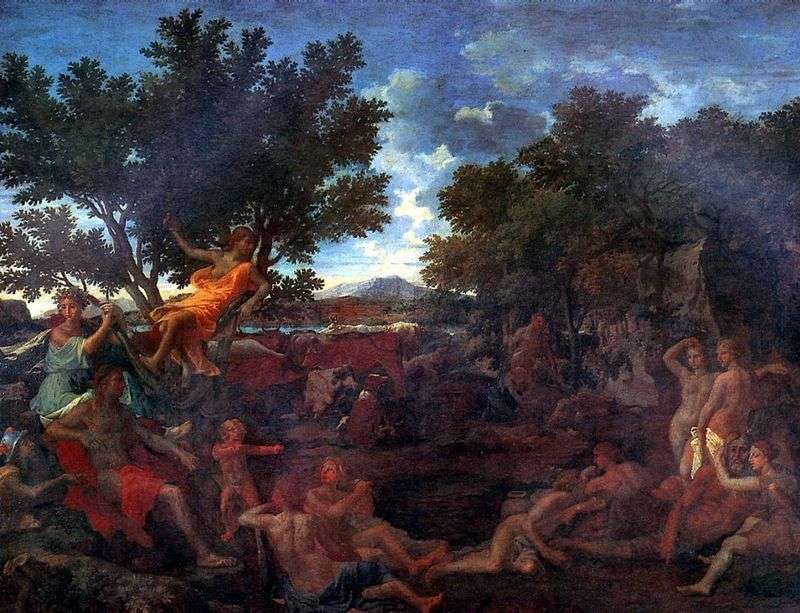

Repentance by Nicolas Poussin Dance in honor of Priapus by Nicolas Poussin

Dance in honor of Priapus by Nicolas Poussin Holy Family with Six Angels by Nicolas Poussin

Holy Family with Six Angels by Nicolas Poussin Apollo and Daphne by Nicolas Poussin

Apollo and Daphne by Nicolas Poussin Danse sur la musique du temps – Nicolas Poussin

Danse sur la musique du temps – Nicolas Poussin Death of Germanicus by Nicolas Poussin

Death of Germanicus by Nicolas Poussin Rinaldo and Armida by Nicolas Poussin

Rinaldo and Armida by Nicolas Poussin Bacchus and Ariadne (Bacchanalia) by Nicolas Poussin

Bacchus and Ariadne (Bacchanalia) by Nicolas Poussin