Bread is a permanent and important leitmotif in the work of Dali. His trademark sign, along with the “fluid” things and prop headstones. In his youth, Dali painted classic still lifes with bread baskets, in mature years he ordered bread furniture and chandeliers for his theater museum in Figueres.

But the true object of interest and the through motive in the artist’s work was, in his own words, bread “aristocratic, paranoid, sophistical, Jesuit, unusual and impotent.” In short, anything, but not bread, capable of saturating the stomach. Batons of phallic form, mounted on the head of characters, with ink pens pressed into the bread crumb. Bread, shockingly stylized as a male genital organ, as the central object of composition, as a self-worth.

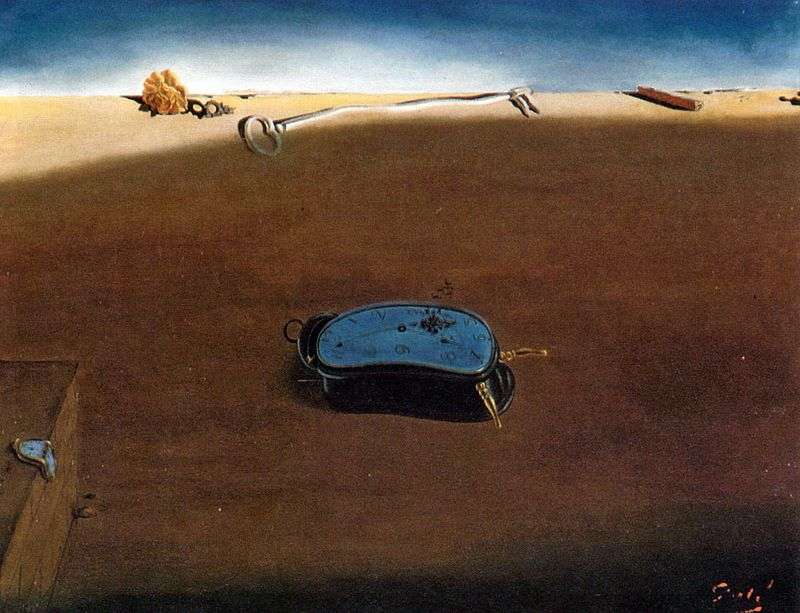

Dali himself admitted that bread is his fetish and a favorite obsession. “Anthropomorphic bread” is a canvas that combined several iconic elements for the artist. Baton phallic form, with the help of twine curved upward in the likeness of an erection. Pressed into it inkwell. A soft flowing clock, a symbol of the relativity of time.

Perhaps this set is random; it is possible that in this combination there is a certain message, “message”. This picture is often interpreted as an indication of the fleeting transience of carnal love in human life or as a hint of aging and the withering of mortal flesh. Or maybe it’s just a few favorite toy objects, extracted by the artist from the bowels of the unconscious and served in a shamelessly provocative still life in the style and colors of the old Flemish people.

Basket with bread by Salvador Dali

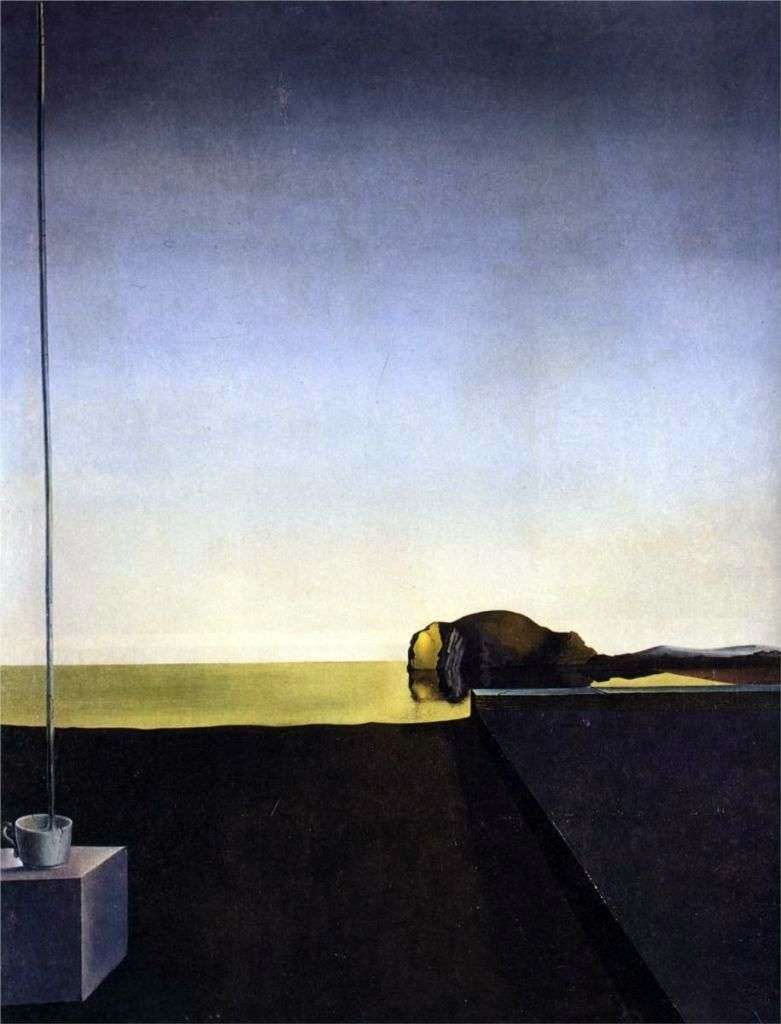

Basket with bread by Salvador Dali Perspectives by Salvador Dali

Perspectives by Salvador Dali Islands of the Dead by Salvador Dali

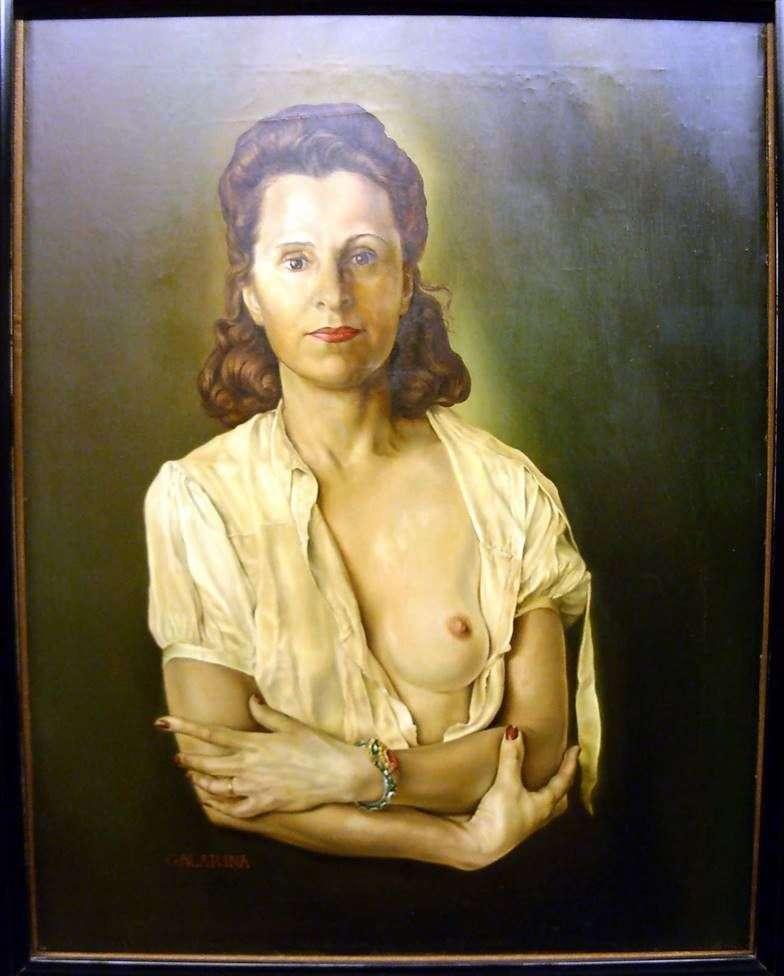

Islands of the Dead by Salvador Dali Galarina by Salvador Dali

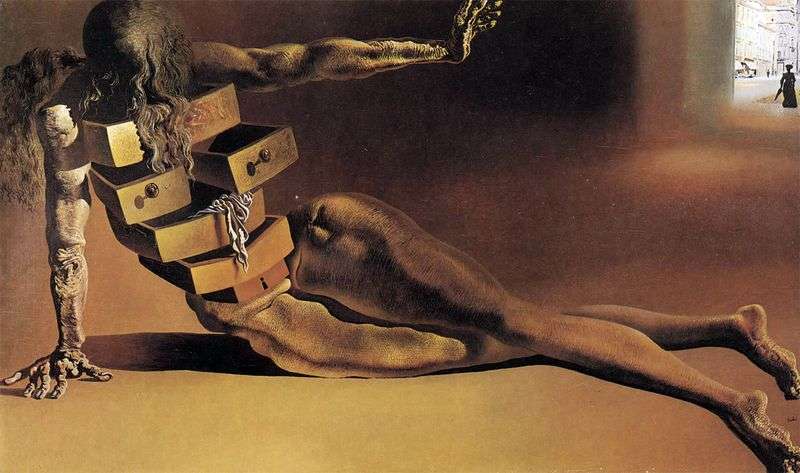

Galarina by Salvador Dali Anthropomorphic locker by Salvador Dali

Anthropomorphic locker by Salvador Dali Soft watches by Salvador Dali

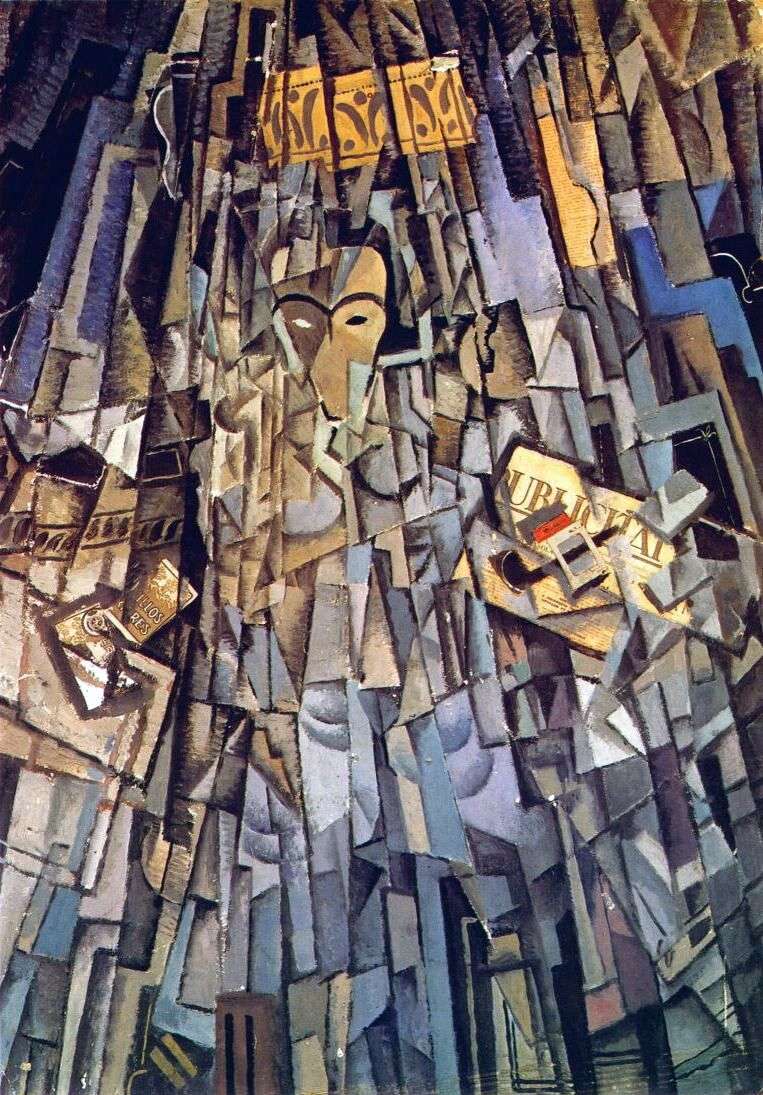

Soft watches by Salvador Dali Cubic Self-Portrait by Salvador Dali

Cubic Self-Portrait by Salvador Dali Live Still Life by Salvador Dali

Live Still Life by Salvador Dali