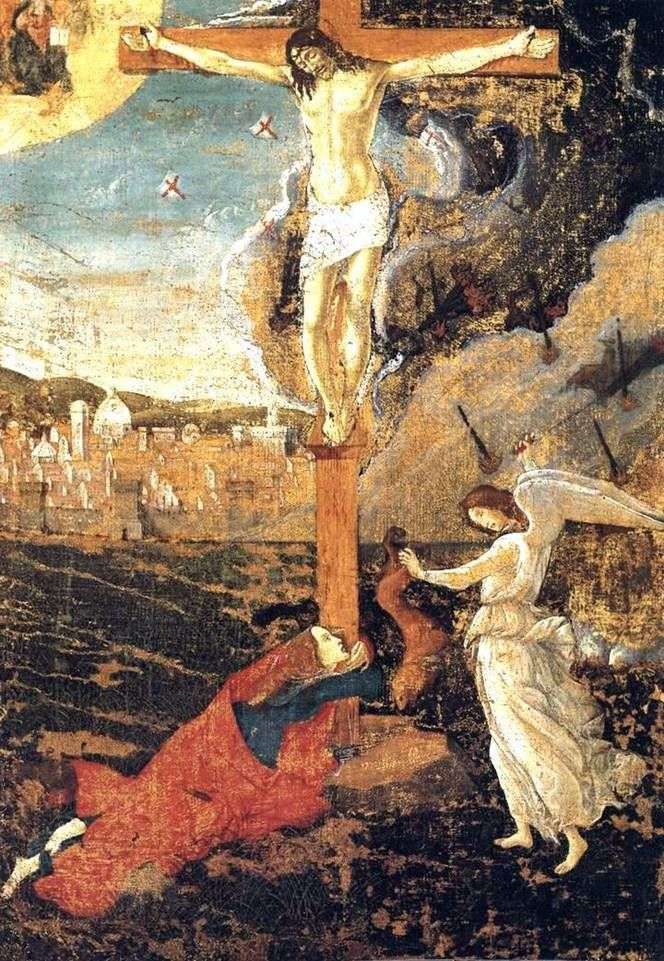

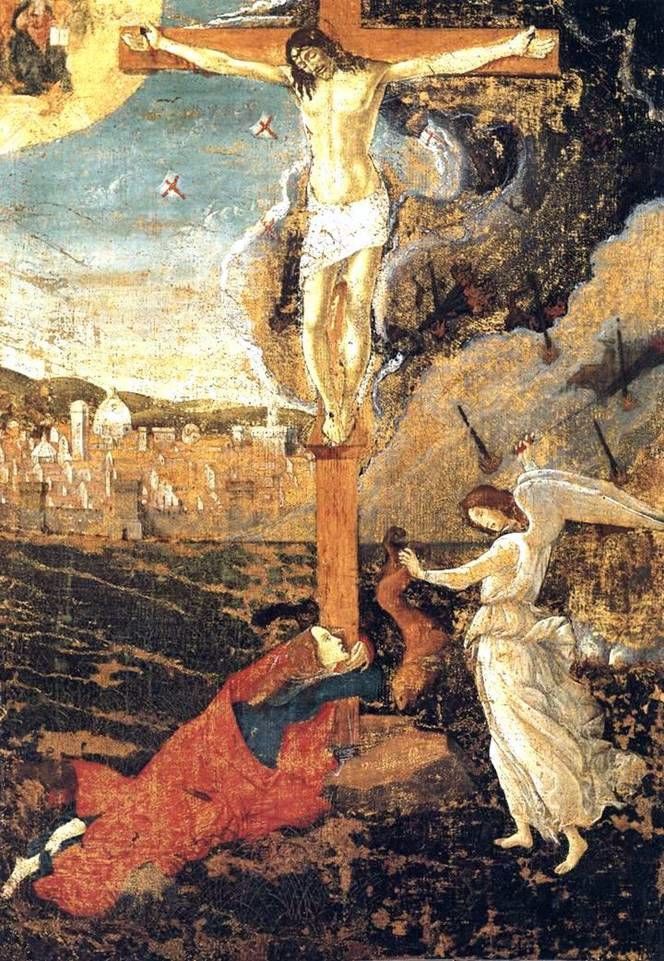

Even less traditionally, the “Crucifixion” of Botticelli, not in vain called “mystical.” Unlike the leading idea of “Christmas” – “Florence must be saved” – in the “Mystical Crucifixion” the motive for punishment of Italy, Florence, the world for the whole, for the immeasurable abyss of their sins prevails. In the agonizing consciousness of a general guilt, part of which lies on him, the painter merges himself with his city in a single repentant prayer to the crucified god, as if born out of the bitter justice of Savonarol’s guess: “If Christ appeared again, he would be crucified again.”

In the painting around the huge cross with the crucified – as the only and immutable center – the gloom gathering in the sky almost merges with the black earth, which lights up under torches, thrown at it by diabolical force. The situation foreshadows the proximity of the inexorable last judgment.

The only saving image of the Sabaoth in the circle replaces the missing images of the apocalyptic beasts, meaning the four accomplished earthly kingdoms, which after their “history will be no more.”

But for the artist the reality here is not so much the mysterious revelation of the Apocalypse, as the terrible “Kingdom of the Beast”, which still counts the inexorable run of time. With one of the apocalyptic beasts, there is a similarity, however, a miserable animal, which is subject to punishment by a slender, majestic angel, resembling the finest times of Botticell’s painting.

With closer scrutiny, the incomprehensible animal turns out to be the likeness of Marcocco, the well-known lion of St. Mark, who was one of the symbolic patrons of Florence. Its insignificant size and even more pathetic position testify to the strictest condemnation by the author of the city, who executed his prophet. Not for nothing that the composition by its conscious “naivety” comes close to numerous anonymous engravings depicting the visions of Savonarola. For the first time in Botticelli mystical ecstasy becomes the immediate subject of the image, but this ecstasy is permeated with pain of the soul and unquenchable humanity.

The cross of the Savior of the world unites all – top and bottom, heaven and hell, good and bad sides of the mystical vision. In his movement, suffering, but almost regal, the crucified god looks alive and conscious. Never before had Jesus Botticelli been so great as this one executed, with his arms stretched out as though embracing the sky. Surprisingly combining the torturing of Christ by the Milanese “Pieta” with the courageous power of the God-man of Munich, it seems like a giant that covers the whole earth, though only slightly larger than the scale of a small woman at his feet. It is no wonder that under his canopy there are apocalyptic miracles that shake the whole of Italy, the whole universe, before the terrible significance of which Florence Sandro is only a grain of the universe.

Especially the sand grains thrown at the mercy of the enraged elements must be felt by the defeated Magdalene, who, without daring to come to the pierced feet of the Savior, selflessly clings to the fray of his cross – a monument to shame that has become a symbol of glory. If crucified Christ exhaustively expresses for Botticelli the inscrutable beginning of divine greatness, then his Magdalene is all infinitely touching, human.

As if through the whole world conflagration the heroine reaches out to the only source of divine justice. But in the “much loved” and much guilty soul, as in Michelangelo later in Eve, “the fear of retribution clearly prevails the hope of mercy.” Now Sandro does not seek harmony between Flor and Venus for her heroine, which is much more punctured by the breaking expressiveness of the dissonant “shift” that gives the entire action a shade of unspeakable anxiety. Through the dynamics of the passionately aspiring movement of the Magdalene, the whole unusual world of catastrophic vision in the “Mystical Crucifixion” is perceived.

Thus, in contrast to the darkened earth, a radiant phenomenon of a magical city, sunlit, emerges. Both are two faces of the same Florence. The shining helicopter on the left, in a free arrangement peculiar to Botticelli, reflects not the letter, but the spirit of the Revelation of John the Theologian about the “new heaven and new earth, for the former heaven and the former earth have already passed.” But it is precisely the “former” land for Sandro that is dear to him. Desecrated by many falls, but beloved despite everything.

Fearing fatal omens, he least of all mourned for himself, but yearned for the fate of his city and Italy and sought to protect them in his own way – painfully dissonant artistic means.

The fabulous glow of the sinless helpline among the pain and sorrow of the Crucifixion and the passionate spell about the almost impossible victory that inspired Christmas is the last gleam of light in the gathering darkness of the last darker and inglorious years of the simple and mysterious life of the once famous painter Sandro Botticelli.

The Crucifixion with the upcoming

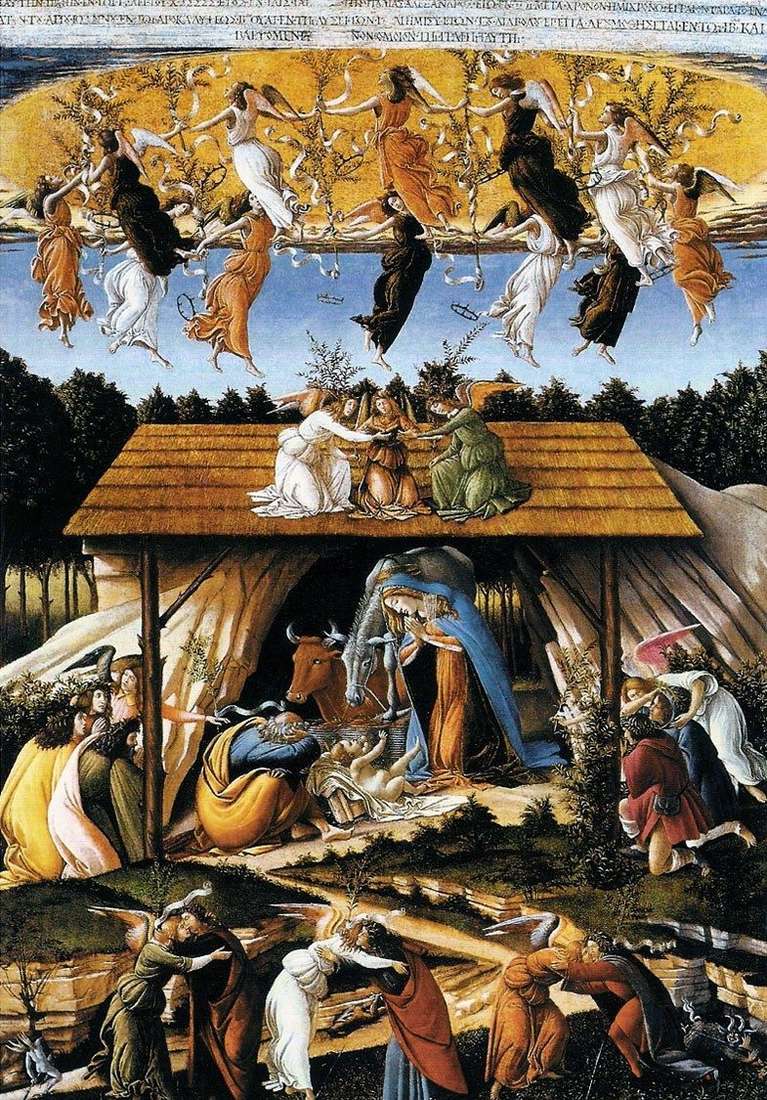

The Crucifixion with the upcoming Mystical Christmas by Sandro Botticelli

Mystical Christmas by Sandro Botticelli Portrait of Simonetta Vespucci by Sandro Botticelli

Portrait of Simonetta Vespucci by Sandro Botticelli Self-portrait by Sandro Botticelli

Self-portrait by Sandro Botticelli Madonna under the canopy (Madonna del Padillone) by Sandro Botticelli

Madonna under the canopy (Madonna del Padillone) by Sandro Botticelli Crucifixion – Sandro Botticelli

Crucifixion – Sandro Botticelli Adoration of the Magi. The altar of Zanobi by Sandro Botticelli

Adoration of the Magi. The altar of Zanobi by Sandro Botticelli The Annunciation of Chestello by Sandro Botticelli

The Annunciation of Chestello by Sandro Botticelli